I found these three spiders under the overhanging cap of consecutive concrete fence pillars. I suspected that these handsome spiders were Steatoda triangulosa because of the distinctive patterns on their abdomen, and I was fortunate that all three were mature. After an hour or so of peering through the scope and looking at Levi’s “The Spider Genera Crustulina and Steatoda in North America, Central America, and the West Indies (Araneae, Theridiidae)”; 1957, I was able to confirm my suspicion. This handsome member of the family Theridiidae is sometimes called the triangulate cobweb spider, for obvious reasons, although it doesn’t seem to be a name universally accepted by the arachnological community.

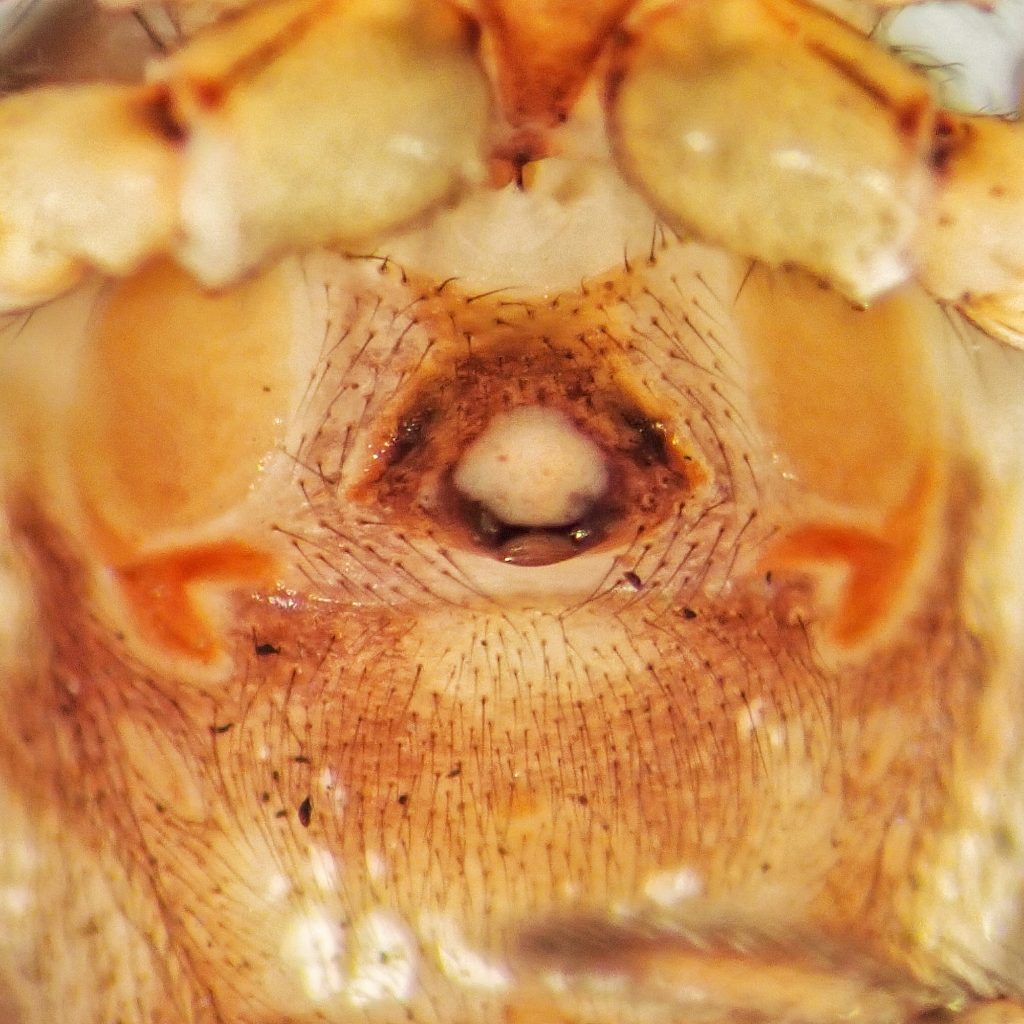

When Rod Crawford confirmed my diagnosis he said that one of my photos “…shows the stridulating organ well (scraper on abdomen rubs against files on back of carapace).” One of the keys I use to get to the family of an unknown spider uses this trait, but I have to admit that I was clueless as to what it might be, and usually skipped that category in favor of things that I could recognize. It turns out that many spiders use these stridulating tools (some utilize their palps and chelicerae to make noise) during courtship and defense, although in a study (https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/151096/1/eth-41622-01.pdf ) of the stridulations of Steatoda bipunctata and S. borealis they say, “Although the mean fundamental frequencies apparently differ between the two species, the frequency ranges overlap so much that it seems unlikely that they could be used as a cue for species recognition. The ranges of the pulse durations also appear to overlap completely. If either species was using either of these parameters for species recognition, narrower ranges, with little or no overlap, would be expected. Also one would expect clear-cut differences between aggressive and courtship stridulations, since courtship stridulations would be under a selection pressure for species-specificity, while aggressive stridulation might not be…These findings are consistent with those reported by Nyffeler et al. (1986) that the pre-mating reproductive barrier between these species is apparently a mechanical one. Females of both species are receptive to courtships of both conspecific and heterospecific males. Males of both species will attempt copulation with heterospecific females, but the differences in the morphology of the two species’ external copulation organs prevents successful insertion of the embolus into the female epigynum.”

“Like other comb-footed spiders (family Theridiidae), these spiders build irregular webs and suspend themselves from these snares while waiting for unsuspecting prey to approach. Using a comb of serrated bristles on their hind legs they enswathe their prey in sticky silk and wait for it to quiet before approaching close enough to bite. Steatoda triangulosa is a frequent associate of the brown recluse and the common house spider in closets and crannies (Fitch 1963). It has been known to prey on many kinds of arthropods, including ants, spiders (including the brown recluse), ticks, and pillbugs (Guarisco 1991). In Texas it has been known to prey on fire ants and spiders inhabiting utility equipment housings (Horner and Russell 1986; MacKay and Vinson 1989).” Triangulate Cobweb | Arthropod Museum

Description– “Adult females are small, cream or tan colored spiders with body lengths ranging from 1/8 to ¼ of an inch (4 to 6 mm). They possess near spherical abdomens with a distinctive pair of broad, reddish-brown, zig-zag bands extending the length of the abdomen. Additional dark areas are present on the lower side of the abdomen. These bands are variable in width and may be wide enough to give the impression of an overall darker brown abdomen with pale highlights. Their surface luster is shiny, with short, stiff brown hairs visible under high magnification. The forepart of the body (cephalothorax) is brown or reddish brown to almost black without obvious markings. The legs are paler, with darker bands. Males are smaller, 1/16 to 1/8 of an inch (2 to 4 mm) in body length with markings that are similar to but less well defined than those of females and a much narrower, oval abdomen. Webs are typical cobweb type, often covering an extensive surface area. Egg sacs are round, white puffballs of silk, 1/5 to ¼ of an inch (5 to 6 mm) in diameter.” Steatoda triangulosa, Triangulate Cobweb Spider (Araneae: Theridiidae)

Similar species– Though the triangle markings on the abdomen are distinctive and unique to this species in our region, positive identification by non-experts of most Theridiidae to species, or even genus,requires microscopy, and a key (this is a key to genera of Theridiidae https://wsc.nmbe.ch/pdfdownload/e83cf47aeccf53b192d936f75e2982b320qkHNdj9hT6wNV, and though it is not a key, this is a good resource for Steatoda sp. v.117 (1957) – Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College – Biodiversity Heritage Library).

Habitat– “In both Europe and North America it lives in houses in the northern part of its range and under stones and on walls of buildings in the southern part of the range (Levi 1957, 1962). It is common in towns and cities, in and around man-made structures, in dark corners of walls, lower angles of windows, and under eaves (Archer 1946).” Triangulate Cobweb | Arthropod Museum

Range– “This species is probably native to Eurasia and has been introduced to North America relatively recently. It is known from central and southern Europe, southern Russia, the Mediterranean, St. Helena, and the United States. It is rare in South America. In North America it is widespread and abundant locally in and on houses.” Triangulate Cobweb | Arthropod Museum;more or less region wide in the PNW in appropriate habitat. However, Rod Crawford says- “This species is rare in the Seattle area (largely occupied by grossa) but abundant in (and outside of) eastern Washington cities.” Observations · iNaturalist

Eats– “Triangulate cobweb spiders feed mainly on small insects and other arthropods, including ticks, spiders (including brown recluses) and pill bugs. They are capable of subduing prey many times their size thanks to a potent insecticidal venom. Prey is detected as it struggles after contacting the sticky cobweb and quickly dispatched with a single bite for leisurely consumption.” Steatoda triangulosa, Triangulate Cobweb Spider (Araneae: Theridiidae)

Eaten by– Presumably a host for parasitoids in Hymenoptera and Diptera, and probably preyed upon by insectivores of all classes, but I can find nothing specific for this species.

Life cycle– “Mating spiders and egg sacs have been found from late spring through early fall (Kaston 1981). Egg sacs, about the size of the adult spider, are made of loosely woven white silk, and about 30 eggs are visible inside each sac.” Triangulate Cobweb | Arthropod Museum; appears to mature in late summer/fall.

Adults active– More or less year around, but few adults in spring/early summer

Etymology of names– Steatoda is from the Greek word for ‘fat/tallow’, though it is likely that Sundevall actually should have used the word for ‘fat/rotund’, since he was referring to the large abdomen. The specific epithet triangulosa is from the Greek word for ‘3’, and the Latin word for ‘angle’, and refers to the triangular markings on the abdomen.

Species Steatoda triangulosa – BugGuide.Net

Steatoda triangulosa, Triangulate Cobweb Spider (Araneae: Theridiidae)

Triangulate Household Spider: A Common Harmless Spider | Nebraska Extension in Lancaster County

https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/151096/1/eth-41622-01.pdf

Triangulate Combfoot (Steatoda triangulosa) · iNaturalist

https://wsc.nmbe.ch/pdfdownload/e83cf47aeccf53b192d936f75e2982b320qkHNdj9hT6wNV

https://pictureinsect.com/wiki/Steatoda_triangulosa.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangulate_cobweb_spider