I have been fascinated by butterflies for several years, and in an effort to better identify them I had joined an excellent and friendly Facebook group, Butterflies and Moths of the Pacific Northwest. At that time the only moth I could identify was the very distinctive, purple and red, day flying Cinnabar Moth, a bio-control agent introduced to combat Tansy Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris). As for the rest, they were just brown and grey things that flew at night that I didn’t have Wiley’s chance against the Roadrunner of identifying.

But then Carl Barrentine moved to our region and joined the group, posting multiple quartets of intricately patterned and beautifully colored moths every day. Now they were on my radar, and I became somewhat intrigued. So, when I saw moths in my wanderings, I didn’t just dismiss them. I tried to get a photograph, and if it was a decent photo someone in that group would identify it. And once in a blue moon, if it was a very common and distinctive moth, that someone was me! But these were all day flying moths, and I hadn’t yet, as Carl likes to put it, gone over to the dark side. Mostly because, as an apartment dweller in an urban area, to find nighttime moths I needed gear and dedication, and I wasn’t that intrigued. Yet.

That all changed on May 4, 2019. During the previous winter, during the seasonal lull for bugs and wildflowers, I had contracted an interest in mosses and lichens. So, feeling financially flush due to working 50+ hour weeks and with the concomitant desire to get something of recreational value to justify spending the bulk of my waking hours working, I signed up for a lichens and bryophytes workshop at the Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center at Jawbone Flats, near the North Fork Santiam River in the Oregon Cascades.

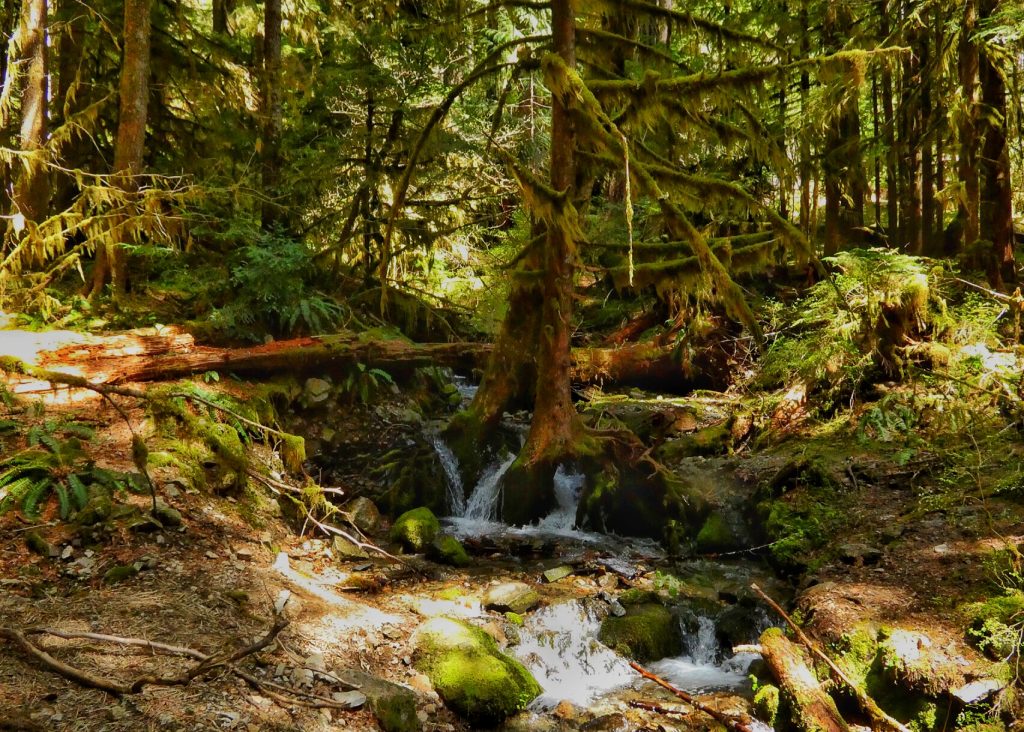

After a beautiful drive up a decent gravel road, past Avalanche Lilies and other signs of spring in the PNW, I met our workshop leaders, John Villella and Maysa Miller, along with the other 6 participants in the class, at the Opal Creek Trailhead at about 10am. It was a perfect spring morning, warm in the sun and cool in the shade, and blue skies from horizon to horizon. John and Maysa proved to be excellent teachers, knowledgeable and enthusiastic about forest ecology in general and lichens and bryophytes is particular.

Unfortunately I missed much of their tutoring because of my low grade A.D.D., which lead to me being distracted by every interesting wildflower, butterfly, babbling brook, or bird we encountered. But they were very patient with me when I finally caught up and asked them if the photo I had finally taken was of the object of their discourse, and btw, what was the name of that species? It’s a good thing there was only one trail in that area because I often fell so far behind that the group was out of earshot.

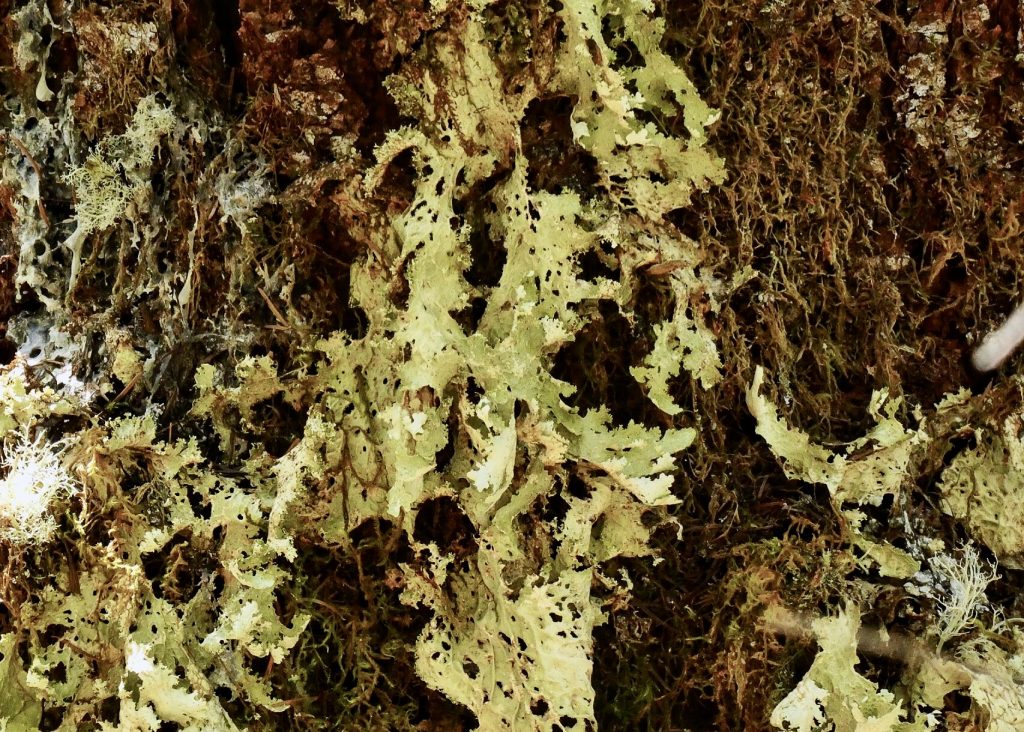

One discourse I was lucky enough to hear in its entirety, primarily because I had hustled ahead of the group to try to identify a dragonfly I saw patrolling a small sunlit area and was waiting for it to return when the group caught up with me, had to do with our first encounter with masses of the lichen Lobaria oregana. This species is not precisely old-growth obligate, but it’s presence and relative population is indicative of the health of a mature forest. As John explained, this lichen uses Cyanobacteria as a photobiont partner to the fungus, and lichens which utilize blue-green algae as a photobiont are very important in these forests because of their propensity for fixing nitrogen from the air, which is later released into the soil when they die and decompose. This is important in any nitrogen poor environment, and in particular in the old growth forests of the Opal Creek Wilderness. This is because, unlike most watersheds in the Pacific Northwest, this one is a salmon desert due to the impassible barrier of Salmon Falls on the North Santiam River. Salmon bring the bounty of the sea to inland riparian valleys where it is spread by the bears, raccoons, birds, insects, etc. which consume the carcasses of spawned out and pre-spawn fish. (They are also consumed by the zoo- and phytoplankton upon which the young salmon feed). When the salmon are lacking it results in a nutrient poor environment. These cyano-lichens help to bridge that gap.

It is also interesting that these lichens prosper in areas with cleaner air, because in the more polluted areas the pollution tolerant species out-compete them, but on the leveler playing field of relatively unpolluted areas the cyano-lichens and other clean air obligate species can hold their own. So they prosper in exactly the places that need them most.

By now you may be wondering, what does all of this have to do with developing an obsession with moths? Overstimulation! By the time we had finished our supper and retired at dusk to the ‘cabin’, (not sure you can legitimately call a two story, 4 bedroom residence a cabin, but that’s what it said in the brochure) I was so jazzed that I could barely sit still. My bunk mates were really good people, warm, friendly, and extroverted, but my meager ability to socialize in groups had evaporated when I quit drinking, and the contrast between my interest level about the things I’d seen and heard that day, (which included at least 50 species of lichens, mosses, wildflowers, bugs and even a mammal, that were all new to me, in a setting which wasn’t much changed from how it would have looked before the settlers arrived) and my disinterest in the conversations about jobs, kids, movies, etc that surrounded me in that overly warm cabin, left me feeling trapped. And then I remembered Carl Barrentine and the moths! So, with the barest of social niceties I fled into the cool, dark evening in search of porch lights.

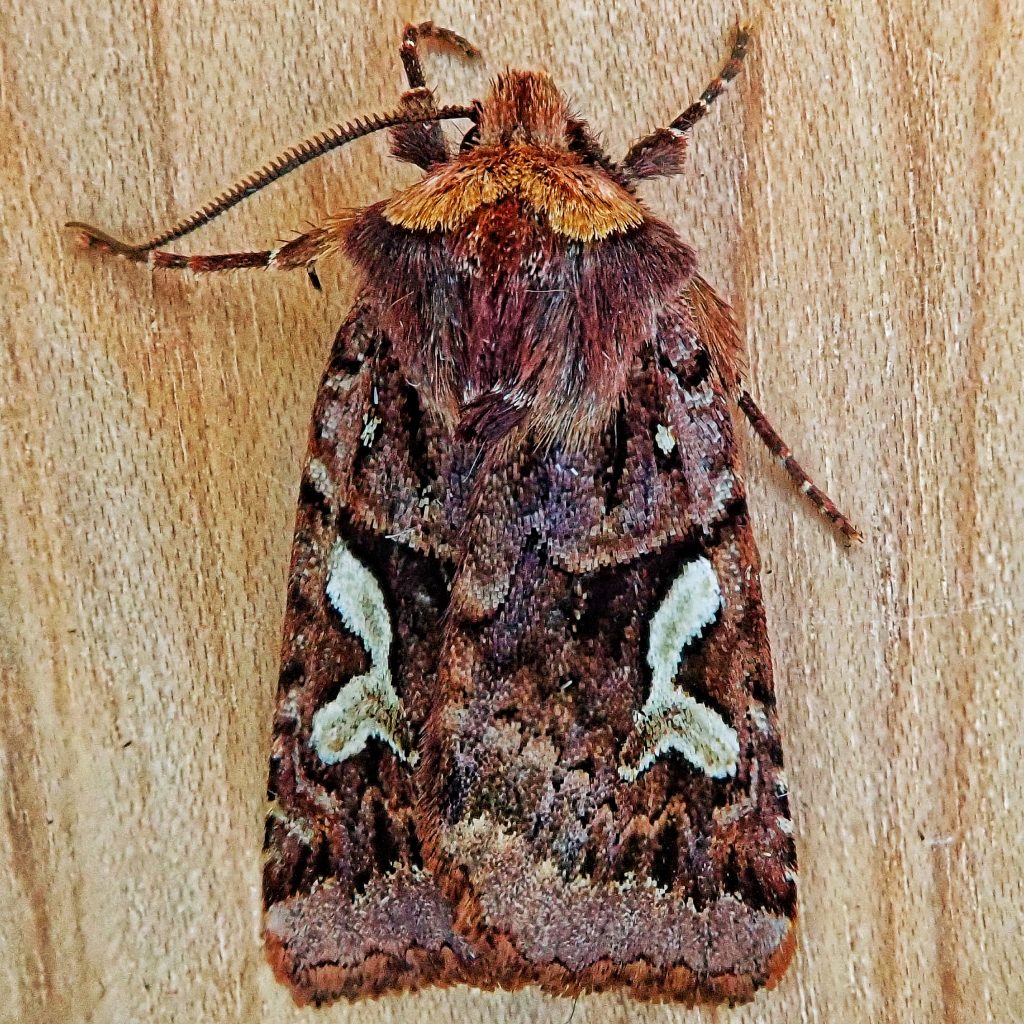

And almost immediately found a moth! A very interesting moth with mint-green coloring, and bold black lines, and black and white checkering along the wing (Feralia comstocki). I took a bunch of photos and moved on to the next light, where I found several small moths with elongated wings and a black dot, which I now know to be members of the virtually-impossible-to-differentiate-without-a-microscope-and-in-depth-knowledge-of-moth-penises genus Eupithecia, and a couple moths probably in the genus Venusia, which I was also never able to identify. It’s rather amusing now how ignorant I was then, and that I actually thought that anything that looked that distinctive would be easy to identify, never dreaming that there could be several different species which were, at least superficially, virtually identical.

As I wandered about in the darkness I walked very close to a deer that I didn’t even know was there until I saw its silhouette against a distant light. Small creatures scurried about in the underbrush, and I heard the distinct ‘who-cooks-for-you’ of a Barred Owl preparing to out compete a Spotted Owl. Then I found a long grey moth with black streaks (Egira crucialis).

During a lull in the action I went back to the cabin to make some tea and gush about how neat it all was, but none of my compatriots, into their third bottle of wine now, volunteered to join me.

On my next round I found 2 grayish tan moths which looked similar yet different (Thallophaga taylorata and Thallophaga hyperborea). I correctly guessed them to be Geometrids, but that was a pure guess without any ‘educated’ about it. Then I found a grizzled grey moth with feathery antenna (Gluphisia severa), and proved how uneducated I was by incorrectly guessing it was a Noctuid.

By then my fellow students had headed off to bed and I sat in the solitude of the kitchen and tried to identify my finds using a pdf on my phone called ‘Lepidoptera of the Pacific Northwest’ by Jeffrey Miller and Paul Hammond, and the book ‘Pacific Northwest Insects’ by Merrill Peterson. And I had some success! Not a lot mind you, but some. I thought the Feralia comstocki was Feralia deceptiva, and couldn’t find anything that looked at all like the Gluphisia severa. But I did conclude that one or both of the Thallophaga was taylorata, and I correctly identified the Egira crucialis!

And, most importantly, beyond just the fun of wandering around in the dark on a treasure hunt for cool bugs, it seemed possible, with the better resources that I knew existed, to actually be able to identify them!

I was really pumped now, and despite the fact that it was well after midnight, I headed out again. But it was pretty chilly by then, and I didn’t see anything new for awhile. Eventually I ended up on the porch of the dining hall, where I saw a good sized black and white moth (Anticlea vasiliata) on the ceiling. Inflamed by desire to capture a photograph of the bug I ended up stacking a chair atop a table, and climbing that to stem a leg onto a window casing whilst jamming the fingers of my left hand into a seam in the ceiling. Thus perched precariously I managed a few one handed shots of the moth. Once I contract the fever, I’m pretty much all in.

That moth, which was eventually identified by Carl Barrentine just before my head exploded, was my introduction to the fact that, just to up the ante on degree of difficulty, and in addition to inter-species similarity, you could have huge intra-species variation.

A year and a half later and I am a confirmed moth-er. I now have several UV lights, and a couple sheet setups to use them with. Heck, my beloved wife Pam even bought me a moth light for our anniversary. I am still far from an expert, but I am learning, and I am even more fascinated today than I was immediately after the trip to Opal Creek. And I really hope you, my good readers, are interested in moths too, because, with 1500 or so species in the PNW, 10% of the lifeforms on this site are likely to be moths.

Maybe the coolest thing so far about this mothing obsession is that occasionally it’s still possible to find something unusual. Last April, mothing with my non-binary offspring (nbo) Morgan up in the headwaters of the Washougal River in Skamania County, Washington, we found a species of Noctuid moth, Cerastis gloriosa Crabo, first discovered 30 years ago by one of my moth mentors, Lars Crabo, which had never been found away from the coast in Washington state. As infinitesimal as that contribution is to our knowledge of the natural world, it is a contribution nonetheless, and a heckuva lot more gratifying than spending an evening in front of the tv.

Lovely story!

Thank you! I don’t know if you’re a subscriber, but if so, I’m sorry it got sent twice. The first one didn’t load properly and cut half of it out. The second one doesn’t have proper links either but I don’t have the energy to fight with it anymore.

I’ve been waiting for this. Good tale.

Thank you!

So wonderful to to hear how the path twisted & turned taking you along with it! Beautiful.

Thank you! For those who hadn’t guessed, this is the wonderful wife I spoke of😀

What a wonderful story! Being a neophyte when to comes to mothing, I was completely out of my league in regards to the more scholastic aspects of the story. However, I still found it completely enjoyable, laughing out loud on occasion, finding the photos beautiful, and the author’s enthusiasm engaging and contagious. Well done, Dan.

Thank you, Vickie!

This is awesome Dan. I always enjoy our conversations as you drive me to my appointments. I love butterflies and I do notice that moths don’t seem that far off. Are they related in some way or are they different and look the same? I have always been curious about this. You take great photographs too.

Hi Jamie! Thanks for the kudus. Yes, moths and butterflies are closely related. In fact there is a school of thought that considers butterflies to just be day flying moths with clubbed antenna😀

Lovely work thank you for sharing.

Thank you, Margaret!

Hi from a new subscriber. First, I wanted to say that I really love the your mission with 10G, am very inspired by this. Kudos! Second: fully relate with getting super excited on multiday camping outings — also happens to me. We can sleep when were dead, right? Third: As a botany n000b, quick question: is the gridded backdrops behind moth pictures, are those standard dimensional botany grids? In general, getting dimensions is tricky — I often include a pen cap or coin in my pictures, and have wondered about conventions. Fourth: thanks again!!

(for example: a Dryocampa rubicunda, the rosy maple moth, I snapped years ago, on our massachusetts door screen, but missing dimensions: https://photos.app.goo.gl/D7JrTTzUqxiDsRbd8)

Nice photo!

Thanks for your kind words, Jasper! For the most part those ‘grids’ are just the weave of the substrate they landed on, whether a sheet or the floor of the decommissioned tent I hang my sheets on, or sometimes the protective mesh around my light. I do use a 5mm grid sometimes when I photograph them at home, but that’s mostly for when I send photos to experts to have the id vetted. Since I try to always have a size range I don’t make a particular point to have a reference in the photos I post with the profile. Thanks again for your appreciation!