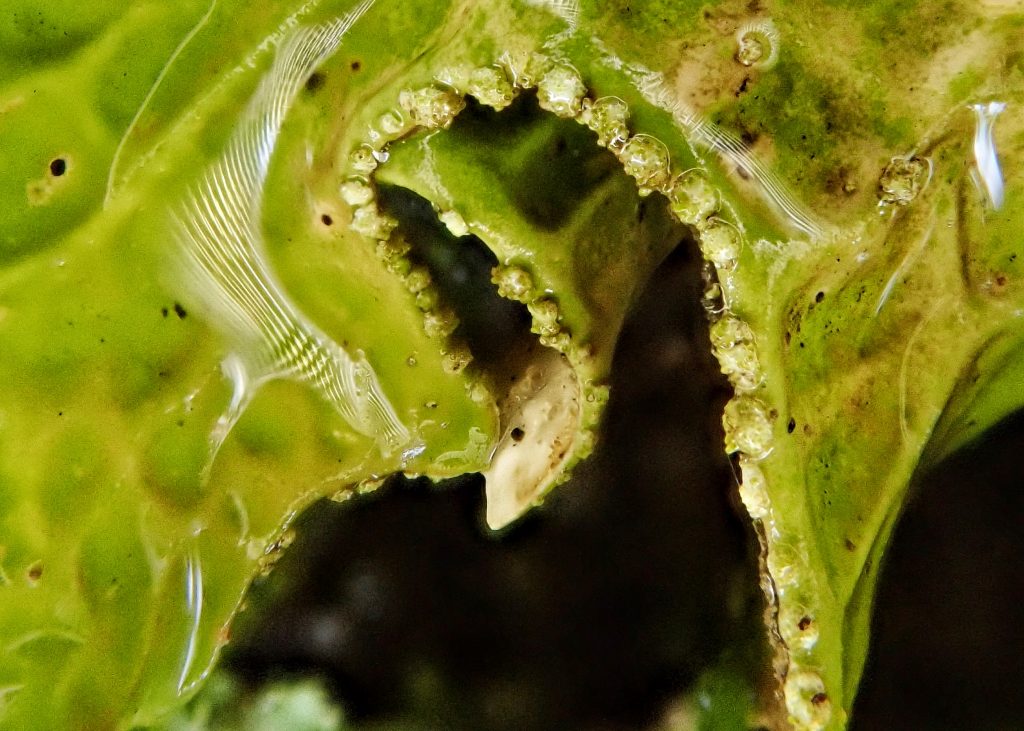

This is both an interesting and an important lichen, for a variety of reasons. It is also a beautiful one, especially during very wet times, albeit slightly grotesque. The photos I took last Friday, after a rare-for-late-fall-in-the-PNW dry week, don’t do it justice, so I went back today and misted it with dechlorinated water, to bring out its lovely green color, and display its true glory.

I also found the cell phone photo I took a couple of years ago, the first time Lobaria pulmonaria impinged on my consciousness. That is a watershed photo, being the first time I ever photographed a lichen with the intent to try to identify it, and the beginning of my love affair with lichens, which admittedly periodically veers off into the mildly pathological territory of obsession.

For me the most interesting thing about Lobaria pulmonaria is that it forms a partnership with two photobionts; a green algae (somewhat unusually for a lichen it is an exclusive relationship with Symbiochloris reticulata) and a Nostoc cyanobacteria. Both photobionts can perform photosynthesis, and the fungal partner shares in the output. The Nostoc cyanobacteria also provides fixed atmospheric nitrogen (as ammonium), which allows the lichen to use these additional nitrogen stores to grow fungal tissue, rather than having to channel limited nitrogen stores into ‘feeding’ the algal photobiont. However, the cyanobacteria have a tendency to specialize in nitrogen fixing to the detriment of their photosynthetic output, so they must be ‘fed’ from the photosynthates of the algal photobiont. But that deficit is made up for by the increased surface area into which the algae can expand. It is an extraordinarily elegant system which provides the maximum benefits to all partners.

The downside is that it doesn’t work well in a nitrogen rich environment, such as one with chemical fertilizers or high levels of nitrogen oxide air pollution, because the additional nitrogen disrupts the balance within the lichenized system. For this reason their population density and overall mass, especially as it relates to historic concentrations, can be used to determine the extent to which urban and agricultural pollution is encroaching on the surrounding countryside. And, because they store elements of the chemical environment which surrounds and washes over them, they can be analyzed to discover what that soup contains.

This pollution monitoring quality is not limited to Lobaria pulmonaria. All lichens are sensitive to their environment. Many, if not most, require clean air and water, while some are very pollution tolerant, and some are even dependent for their survival on high levels of what we would call pollutants. Given the vast array of chemical requirements encompassed by lichens the make-up of the lichen community and each species’ relative population gives, to a trained observer, a snapshot of the chemical components, and their concentrations, in a particular environment.

From the standpoint of the ecosystem they inhabit the most important thing Lobaria pulmonaria do, along with any of the other lichens containing nitrogen fixing cyanobacteria (collectively called cyanolichens), is to die and fall to the forest floor to decompose, thereby cycling that nitrogen into a nitrogen poor environment. This has become particularly important in recent times in the Pacific Northwest, because of the drastic decline of salmon of all species.

For at least the last 4 million years salmon have been bringing the bounty of the sea back to their natal rivers. As they made their way home many were eaten, and their nutrients were disbursed to the surrounding areas. When they died after spawning it was a feast for many of the local animals, vertebrates and invertebrates both, who further disbursed those nutrients through their scat. And the decomposition of spawned out salmon fed the zoo- and phytoplankton that are the basis of the riparian food chain, a chain which included their progeny. Virtually every watercourse had its salmon run, and the ecosystems that evolved have a dependence on that stupendous influx of nutrients, which is now but a tiny fraction of what it was before colonization.

This is true despite the fact that with hatchery production the numbers seem good, because the wild salmon populations are still abysmal, and those are the fish that would be spawning and dying in the small tributaries of the major rivers. And those big numbers of hatchery fish? Mostly harvested at the hatcheries and removed from the riverine system, often going to commercial fish food and fertilizer making companies, though some are given to food banks. There has been some effort made to place them back into the stream, but those efforts are almost all directed at returning them to the major rivers themselves, mostly to sustain the food chain supporting the smolts upon their release from the hatchery.

Nothing can replace those billions of pounds of nutrients, natural fertilizer that each watershed was evolutionarily adapted to, but every little bit helps. I know people like to dye wool with these lichens, and some will say that they are only gathering ‘useless’ blowdowns. But that is precisely when they are performing their most vital function. Please leave them be, wherever you may find them. Climbing off my soapbox now.

Lichens are difficult to differentiate without magnification and a key. There is a great interactive key at Common Macrolichens of the PNW. It has excellent photos of all key characteristics.

Description-Large, lobed thallus, gray green to bright green depending on moisture content, with conspicuous ridges and hollows, which suggests the form of lung tissue; underside has very light, off white, raised bumps, with light brown valleys between them; it seldom has apothecia, but mature specimens always have soredia and usually have isidia, usually on the ridges and margins; soredia on immature specimens may be lacking or sparse; may have lobules on old specimens.

Similar species– Lobaria oregana is usually yellower green when wet, and has lobules, giving the margin a ruffled look, but lacks isidia, soredia, and usually apothecia; L. linita is rare, and has apothecia, but lacks soredia and isidia.

Habitat-Found mostly on deciduous trees in moist lowland forests. More common on old growth conifers east of the Cascades

Range-Most common west of Cascades; also found in northern Idaho and western Montana.

Etymology of names– Lobaria is from the Latin for ‘many lobed’, and refers to either the lobed thalli of many species in the genus, or for their propensity for forming lobules. The species epithet pulmonaria is from the Latin for lungs, and references its lung like appearance. A colloquial name is lungwort (a wort in Olde English being a plant with nutritional or medicinal value), because ancient herbalists thought the appearance of a plant was a cue to what it might heal, and this lung looking lichen was used to treat pulmonary ailments.

https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/lobaria_pulmonaria.shtml

https://www.britishlichensociety.org.uk/resources/species-accounts/lobaria-pulmonaria

https://mlbs.virginia.edu/organism/lobaria_pulmonaria

https://www.centralcoastbiodiversity.org/lungwort-bull-lobaria-pulmonaria.html

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lobaria_pulmonaria

https://psmsblog.com/2016/02/26/local-lichen-lobaria-pulmonaria/amp/

I love seeing the dry before and hydrated after photos. Beautiful species.

Lovely, I picked up (no worries I later put it back, though not in the precise spot) what i am pretty certain was this lichen while out walking the dogs through a regrowth area of sitka alder and black cottonwood. It was such a beautiful green. I tucked it in my pocket to take home and sketch/paint. I forgot it was there until the next day. When I pulled it out it had changed to a medium brown color and was leathery rather than rubbery. I thought to put it in a puddle in my yard and in minutes it had changed. I am in Alaska, Kenai Penninsula, so perhaps the range is further north?

Yes, they range all the way up to you. I don’t have a way to put maps in the post, so I just talk about the range within the proscribed area of my quest. I talk about that in the mission statement, so I won’t bore you with it now😀

Just identified my first lichen–Lobaria pulmonaria, on an apple tree in a heritage orchard. The tree, I am told by the former orchard owner (family in area since 1775), is “way more than a hundred years old”. I know folk working the same orchard in the 1950s and it was old then. I have photos. I am leaving it on the tree, but rejuvenating the whole orchard (at least 7 heritage varieties). It will take time. Location: Maritime Canada, flanking tidal river. Critters: white-tailed deer, raccoon, porcupine, turkeys (not seen bear for 4 years), grouse, bald eagles.

That’s really cool, Jenny! Thanks for sharing that! I’ll bet there are dozens of lichens to be identified in that orchard. Sounds like a nice diversity of vertebrates. Have fun and good luck!

The link identified as “There is a great, interactive key here.” doesn’t work

Not sure why that link went dead, Paul, but it’s been updated and should work now.