Last week I decided to start taking my Olympus TG5 to work with me, because sometimes I see interesting critters and other lifeforms, and I’m never satisfied by the macro shots my phone takes. Not that they are horrible. It’s just that I’ve become spoiled by the in-camera focus stacking ability of the TG5. That camera makes me look like a much better photographer than I really am. If this sounds like I’m doing a commercial for Olympus, I’m not. Nobody is paying me to shill for them, though I would if they asked.

My day job is driving medical transportation. Basically I take people to doctors appointments and medical treatments. Most of them are in wheelchairs, many of them live in facilities of some sort, and few of them are actually ready to go when I arrive. During this pandemic, because I’m seldom permitted to enter these facilities, I spend a lot of time in entryways and on porches. And the lights there attract bugs, which often remain during daylight hours because the area is sheltered.

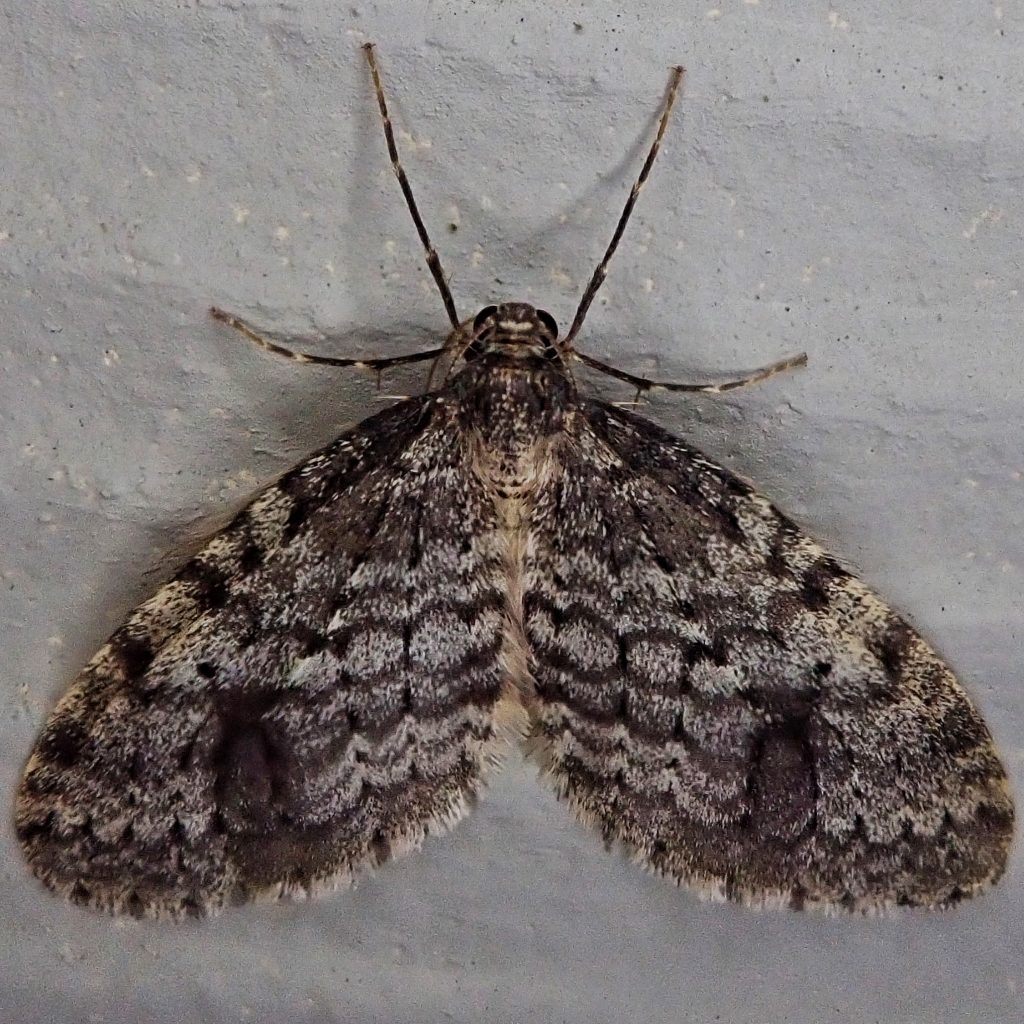

Which is what I encountered on Tuesday, when I found three different specimens of one of our few winter flying moths, the Geometrid Operophtera occidentalis (recently elevated to full species status after being O. bruceata ssp occidentalis for decades). And I do mean different! One might be tempted to think these are 3 different species based on the scale patterns (maculation). And I have to confess that I at first thought the lightest colored one, with the bold transverse lines, was O. danbyi. But before being slapped down by the misidentification police, in the form of Tomas Mustelin (who confirmed all 3 as Operophtera occidentalis), I pored over dozens of photos of the variation in this species, and realized my mistake on my own.

One of the reasons for the extreme variability in this species is that it is prone to ‘industrial melanism’. Specimens tend to be much darker in urban areas, a camouflage adaptation that allows them to blend in better in sootier urban environments. This adaptation was most famously noted in Biston betularia (Peppered Moths) in the late 1800s, and was hailed as a real time example of natural selection in action, lending credence to Darwin’s shocking, at that time, revelations about evolution.

So, dividends reaped by having my great little camera with me, and irritated impatience averted. That’s what I call a win, win situation!

Description– The females have only vestigial wings, like other members of this genus; Males are shades of brown and gray, with a single row of black dots delineating the terminal line, and black veins running down the wing.

Similar species– Epirrita autumnata has paired spots on the terminal line, and flies earlier in the fall; Operophtera brumata has less pronounced black veins and terminal spots, and usually has a darker or lighter swath running transversely through the middle of the wing. O. danbyi has more jagged and irregular scalloping of the transverse lines, and they are spaced more widely apart.

Habitat– Woodlands and forests containing alder, willow, maple and other larval hosts.

Range-West of the Cascades.

Eats-Larval hosts include maples, alders, and willows.

Adults active– October to January

Etymology of names– The only definitive answer I can find on the meaning of Operophtera is that it is a misspelling. Of what they don’t say. My guess would be ‘operoptera’ which would break down into ‘work wing’, but again, I don’t know what that might reference. The species epithet occidentalis is a common appellation for western, and this recently elevated species is only found in far western North America.

https://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/forest_health/insects/bruce_spanworm.htm

https://www.forestpests.org/vd/195.html

https://bugguide.net/node/view/9745

http://mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu/species.php?hodges=7437

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peppered_moth_evolution

Great pictures of beautiful moths! 👍

Thank You for sharing all that you do educational kindness great pics

Thank you for your appreciation!