Last Sunday I made the leap and took a grass workshop with Cindy Roché (co-author of the wonderful book “Field Guide to the Grasses of Oregon and Washington”, 2019). It has long been my contention that grasses are just too hard to identify, and ‘that way lies madness’. But since moss identification has already lead me down a path into the abyss of insanity (and I had found that I liked the view), I decided to see what other trails there were in the area.

I made two big mistakes as regards this class. The first only really effects my ability to profile species, and that is that I failed to get in situ photos of most of the grasses we identified. The second was more egregious. I was woefully unprepared for this class, having only glanced over the vastly different terminology used in grass identification, and I didn’t do the work necessary to truly familiarize myself with the terms. This resulted in my quickly being multiple steps behind the class with each grass we looked at.

Cindy, who is an excellent teacher with a tremendous amount of knowledge and patience, was willing to slow things down to accommodate my ignorance. But that didn’t seem fair to the rest of the class, who were all much more knowledgeable than I. I still learned far more during this class than I came into it knowing, and will certainly know much more before the next time I take a grass workshop. And it did awaken in me an interest in trying to figure out at least some of the common grasses I encounter.

Grasses are angiosperms, which means they are fruiting (flowering) plants (technically it means they have seeds that are fertilized while enclosed by an ovary, unlike gymnosperms [literally ‘naked seed’ in Greek], like conifers, which have an exposed seed that is directly fertilized).

They are monocots, which means they have a single embryonic vein leading to a single embryonic leaf, or cotyledon (as opposed to dicots [which comprise the bulk of what we think of as flowering plants, shrubs, and trees, such as roses, sunflowers, heaths, mustards, peas, and dozens more families] which have 2 veins and therefore 2 cotyledons). They also usually have parallel rather than diverging leaf veins. Monocots that may surprise you by being un-grasslike include the lilies, irises, and orchids.

From here we jump to the order Poales, which includes the grasses, sedges, and rushes. As the old rhyme goes, ‘Sedges have edges, Rushes are round, Grasses have nodes from the top to the ground’. Rushes and sedges do not have joints (nodes) in the stem (culm), and sedges have a solid culm (which is usually triangular).

Finally we are in the family Poaceae, the grasses, which have a whole different, specialized terminology (quick glossary here), for structures that may be analogous to other orders of plants, but are certainly not the same. Grass nodes are solid joints in the culm from which the leaf sheath issues, and the extent to which the sheath is open or closed is an important identification trait. The sheath becomes a collar where the blade of the leaf extends away from the culm, and on the inside of the collar are little projections called ligules.

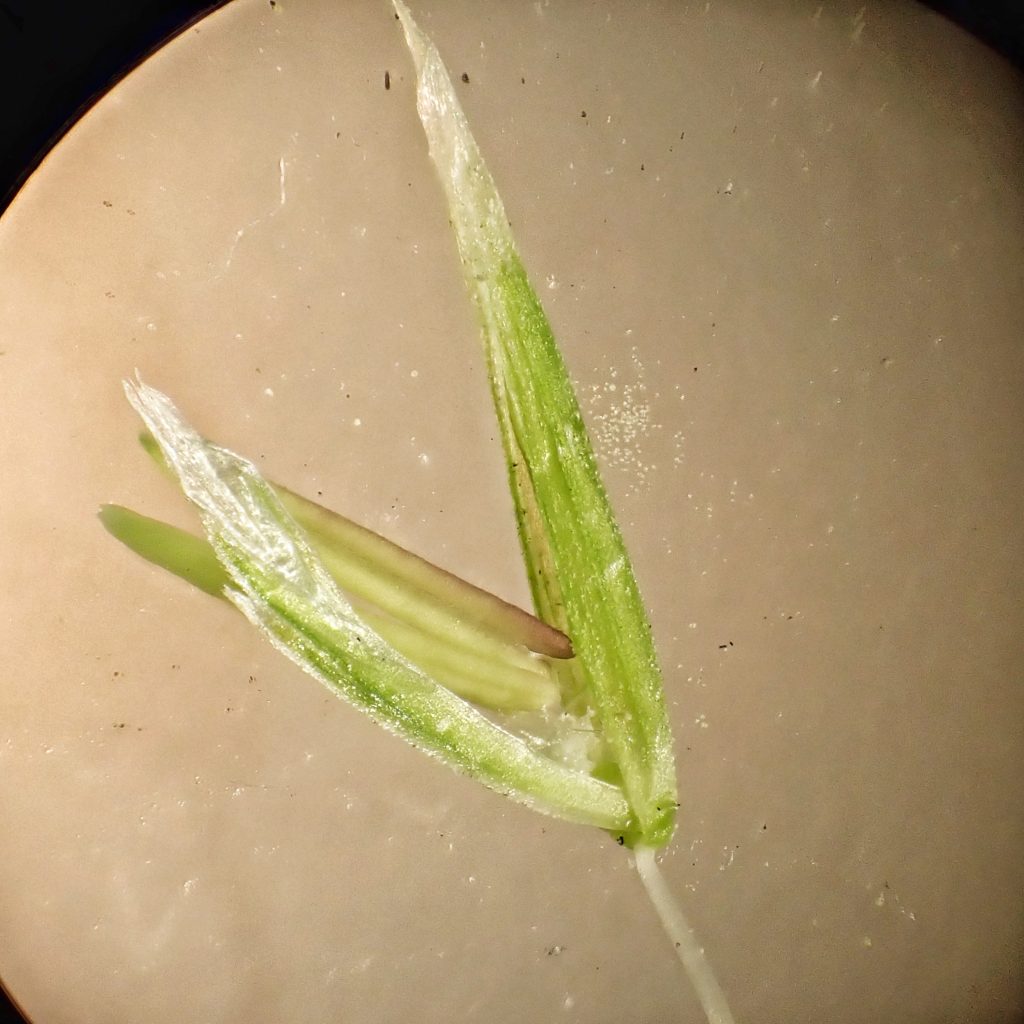

The parts of the inflorescence are called spikelets, and the arrangement of spikelets is described in conventional botanical terms such as spike, raceme, and panicle. The spikelets themselves consist of a pair of bracts called glumes, which are at the base of the string of florets. Each floret has two bracts, called the lemma and palea. All of these bracts may or may not be awned, and those distinctions are usually critical to identification. Within the lemma and palea is the flower, which is mostly described using conventional botanical terms. One thing to notice is that the stigmas of a grass flower look like tufts of cotton wool.

If one decides to try to identify grasses I would highly recommend “Field Guide to the Grasses of Oregon and Washington “ (Roché, Brainerd, Wilson, Otting, Korfhage; 2019). Cindy et al. have written a comprehensive book which includes 376 species, virtually all of the grasses one might find growing wild in Oregon and Washington, along with a full glossary, some history of human usage, a well thought out and relatively straightforward key, and an alphabetical layout that makes finding keys to genera, and the species therein, a breeze. You will also need a good hand lens or stereoscope, probably a chair or stool if doing field identification, and more than a little patience. But I think this will be a rewarding venture.

Description-Perennial with rhizomes; fairly tall (up to 60”) grass with spikelets all on one side of the stem, which bends (nods) as the tip matures ; sheath is open almost to the base; leaf blades up to 14mm wide, end in a point or a tiny (less than 3mm) awn; palea has triangular appendage; lemma with long (up to 20mm) awn.

Similar species–P. oregonus, is rare (presently known only from a few spots in e Oregon), usually has longer spikelets (up to 50mm long), has awned palea, and often has awns on the leaftips.

Habitat-Widespread but uncommon in moist areas in meadows and shaded woods, and along streams, up to 5,000’.

Range-Native from BC to n California; primarily west of the Cascades in our region, with some extension to the east slope of the Cascades. According to Cindy the population along the Metolius River is, to her knowledge, the farthest east this species reaches.

Reproductive timing-May to August

Eaten by-Many Lepidoptera utilize grasses as larval hosts, but there doesn’t seem to be a lot of information about specific species of plant or insect; various herbivores, both vertebrate and invertebrate, also graze a wide variety of grasses, but specific information is negligible.

Etymology of names–Pleuropogon means ‘side beard’ in Greek, and refers to the spikelets all being on one side of the stem. The specific epithet refractus means ‘stubborn/contentious’ in Latin, but I can’t ascertain what that references

OregonFlora Pleuropogon refractus

https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=38716

https://cals.arizona.edu/yavapaiplants/Grasses/GrassGlossary.php

The sedges is where it’s at.

Well, I’ll be going there too. I know there are lots of bugs that eat sedges. Looking forward to it!

I thoroughly enjoyed your sharing your view from the “abyss of insanity “! You may as well go all in, not a lot of sanity to protect! 🤣 Seriously, though, I love the delicate quality of the photos. Well done 👍 & thank you ☺️

You are being too rough on yourself in describing your “big mistakes.” First, almost no one memorizes the names of grass parts before they really understand how they will use this knowledge. This is why I don’t lecture on the topic for a couple of hours at the start of the workshop. Second, photographing the “gestalt” in situ is extremely difficult for most grasses. They blend into the background or mingle with each other to the point that you will not be able to pick them out through the camera lens. Only when you have an uncluttered background or a grass that is bulky enough to focus on will you be able to see the individual plant. You’ve done extremely well for the first encounter with curing grass blindness.

Thank you, Cindy! It was, and will continue to be, a fascinating immersion.