I am somewhat embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know we even had multiple genera of freshwater mussels in our region. I had seen the very dark ones (probably Margaritifera falca) in some faster moving streams, but hadn’t really considered that there might be others, since apparently I don’t spend a lot of time along the Columbia River at low tide, or peering into the shallows of ponds and watercourses. These mollusks are mussels in the family Unionidae (river mussels). The taxonomy of the genus Anodonta is in flux, because genetic research has discovered that several of the species, which had only been identified previously via their highly variable shell morphology, are molecularly very similar. That similarity between these two species is why this profile is titled with two names. The term ‘floaters’ for this genus of mussels comes from the fact that their thin, light (and easily fractured) shell allows them to ‘float’ on a layer of sediment.

Mussels have an interesting life cycle, wherein the larval stage, called glochidia, attach to the fins or gills of a host fish shortly after hatching. They create cysts in which to abide, and derive some nutrition from the fluids of their host, although they don’t seem to damage them, unless the infestation is large enough to disrupt gill functioning. They also get a free ride to locations that are potentially far from their parents, an important dispersal factor for a creature of limited mobility like a mussel, which may pass the remainder of its life within scant yards of where they landed after releasing from their host. Some mussel species are very host specific, but western Anodonta spp. do not seem to be. There is only limited information on hosts of A. nuttalliana/californiensis, but they have been found on Gasterosteus aculeatus (Three-spined Sticklebacks), Ptychocheilus oregonensis (Northern Pikeminnow), and the non-native Lepomis cyanellus (Green Sunfish). Cottus spp. (sculpins) are also likely candidates, since some do host these mussels in the Sacramento River basin.

Freshwater mussels are important in the food webs of the ecosystems they inhabit, due to the fact that they filter algae, bacteria, zooplankton, and suspended particles from the water, and deposit them in larger, somewhat decomposed clumps, within the substrate, where they in turn feed other invertebrates and plant life. They also reduce the turbidity, and regulate the nutrient levels, of the water they inhabit. The shells of both living and dead mussels provide shelter and substrate for algae, moss, and aquatic invertebrates, and they are fed upon by a variety of creatures.

Anodonta were not a major food source for indigenous peoples and early settlers, apparently because they were not particularly tasty. But, since they were always available, they were utilized during times that more palatable food was not available, as evidenced by their presence in shell middens. Freshwater mussels in general face many threats, and Anodonta spp. are no exception, having already been extirpated from many parts of their historic range. These threats include, but are not limited to, dams, impoundments, loss of host fish, dredging and channelization, mining for sand and gravel, pollution, excessive nutrients, higher water temperatures, and livestock encroachment. It is now illegal to harvest (or even possess without a scientific collection permit) any freshwater mussels in Oregon or Washington.

This profile is merely the tip of the iceberg regarding the fascinating lives and ecological value of Anodonta nuttalliana/californiensis. If your interest has been piqued I highly recommend that you check out “Freshwater Mussels of the Pacific Northwest” (Nedeau et. al.; 2009). For a deeper dive it’s definitely worth reading the profile of this clade (Jepsen et. al.) put out by the Xerxes society. And the next time you are wandering the shoreline of a body of water, scan the shallows and see if you can spot any of these remarkable creatures of liquid environments. They’ve certainly opened my eyes!

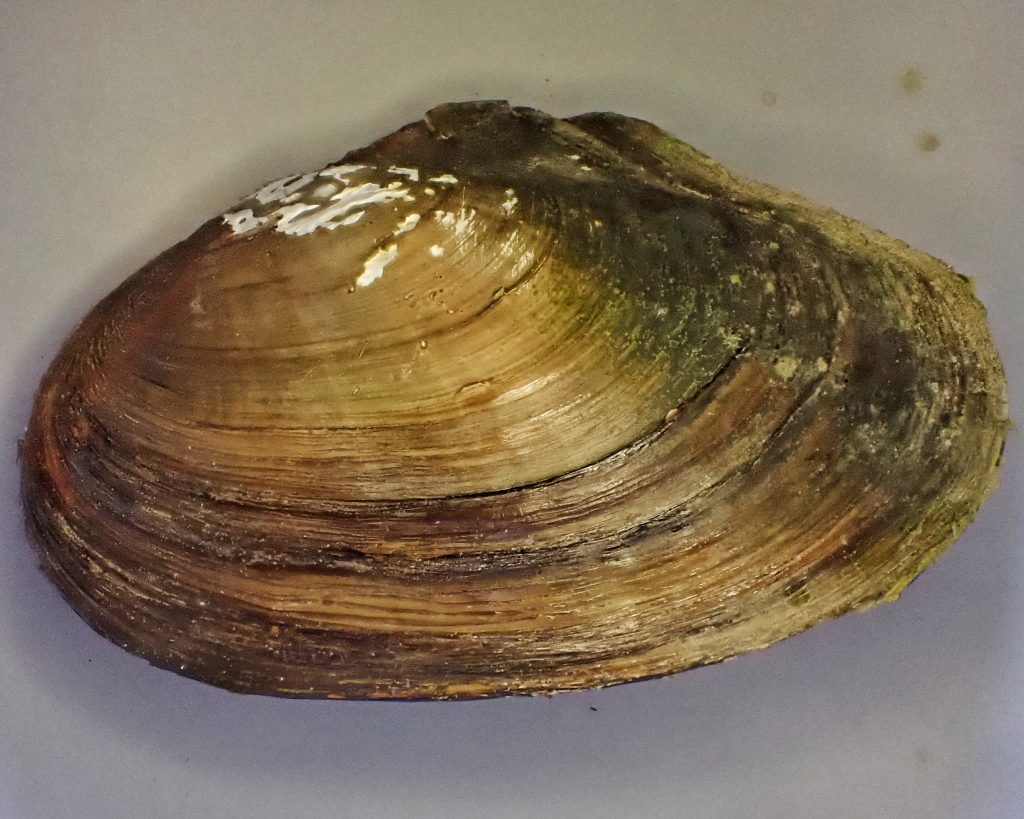

Description-Medium sized (up to 5”) mussel that is only about 1.5x as long as tall; Periostracum (outer surface of the valve [shell]) variably colored yellow, green, brown, red, black, or combinations and shadings of any or all of those; beak (shell apex) is small, domed, only slightly higher than the hinge; there is a variably sized ‘wing’ where the valves are compressed near the hinge; nacre (shell interior) usually white, sometimes with a salmon, purple, or blue tint.

Similar species–A. oregonensis/kennerlyi usually at least twice as long as wide, and the wing is lacking or much reduced; Margaritifera falcata is uniform dark brown to black; Gonidea angulata is uniform brown to black, with an angular ridge that runs from the beak to the margin.

Habitat– Silty and sandy portions of low gradient rivers, lakes, and reservoirs; may be found in faster streams and rivers with sandy pools and other slow moving sections.

Range-Western North America; Columbia River and its tributaries, and in appropriate habitat scattered throughout our region.

Eats-Glochidia (larvae) feed on their piscean hosts; after dropping from the fish to the substrate they are filter feeders, consuming zoo- and phytoplankton, and floating detritus.

Eaten by– Carp, catfish, muskrats and river otters feed on the submerged mussels, and gulls, shorebirds, raccoons, skunks and other mammals feed on those that become exposed, although the birds mostly scavenge dead ones.

Reproduction-Generally have two sexes, but occasionally hermaphroditic; males ‘exhale’ sperm into the water, and if they’re lucky, fertile females ‘inhale’ them; spawning usually takes place in summer, and glochidia are released in late fall or early spring; glochidia lucky enough to find a host attach to it and encyst in 2-36 hrs; those that attach to a host in the fall may overwinter encysted, while those that attach during warmer months may metamorphose fairly rapidly; sexual maturity usually occurs in 4-5 years, and lifespan of the mussel may be 15 years.

Adults active-Siphon usually exposed during all of the warmer months, and the mussel is often buried in the silt during colder periods.

Etymology of names–Anodonta is from the Latin for ‘without teeth’, and refers to the lack of teeth on the hinge. The specific epithets nuttalliana and californiensis refer to the naturalist Thomas Nuttall, and to the location of the type specimen in the state of California, respectively

https://www.fws.gov/columbiariver/mwg/pdfdocs/Pacific_Northwest_Mussel_Guide.pdf

http://xerces.org/sites/default/files/publications/10-029.pdf

Perfect,

As always!

Thanks. Keep it up. Very much apprecited!

Jochen