Last Thursday, thanks to certification by people who obviously don’t know me at the Universal Life Church (though henceforth I would prefer to be addressed as Reverend Nelson, although Rev Dan would be acceptable 🤣😏😉) I had the honor of officiating at the marriage of my nbo Morgan and their partner Jun. It was a glorious, albeit historically warm, fall day, and it felt good to be in the streaky shade of a huge Oregon white oak as we legally codified the existing commitment and love of these two wonderful people. And, whilst grokking in the fullness of the setting, I noticed that there were a couple Oregon Ash (Fraxinus latifolia) that were standing alone near our temporary cathedral.

I’ve seen many Oregon Ash over the course of time (in fact I planted about 75 of them on MLK day in 2011, as part of the rehabilitation of the former lettuce fields in the greenway along Burnt Bridge Creek in Vancouver , Washington), and it’s possible, even probable, that I’ve seen them isolated from other shrubs and trees. But every time that I’ve noticed them and it has occurred to me to get some photos for a profile, they’ve been crowded by willows, alders, cottonwoods, elderberries, Pacific ninebark, or some other tree or shrub. I’ve wanted to profile Oregon Ash for quite awhile, because they are an integral part of the usually dense, low elevation bottomlands, often vernally wet (but not actual permanent wetlands), woodland ecosystem found along the Lower Columbia River and its sloughs and tidally influenced tributaries, and this is a habitat I frequently visit, because there are large tracts of this relatively wild land that are only a few miles from my home.

As I said, these trees (the only ash tree native to our region, and which shouldn’t be confused with mountain ash, which is in the genus Sorbus in the rose family, while Fraxinus latifolia is in Oleaceae, the olive family) are integral to the ecosystems they inhabit, providing food and shelter to dozens of animal species, both vertebrates and invertebrates. They have a high tolerance for flooding and heavy soils with poor drainage, and are useful soil stabilizing agents in the floodplains where they are frequently found, because of their shallow, but wide spreading root systems, which also protect them from being knocked over in high winds, or the currents associated with flooding. They also have a characteristic that is endearing to birders, which is that they flower before they leaf out, so that they are one of the few trees with unobstructed limbs when the spring migration of birds is moving through.

Ash trees in general are a valuable hardwood species, prized by furniture makers and stair builders for its durability, and it is often used for baseball bats and axe handles. Many early cars (mostly those built by carriage makers) utilized ash for the frame, because of its flexibility. Because it is often located in riparian areas and other sensitive ecosystems, the harvest of Oregon Ash is significantly restricted by regulations governing those areas. Saplings are moderately shade tolerant, but react quite positively to any new openings in the canopy, and these trees grow rapidly for the first 60-80 years, often reaching almost their maximum height in that period, and thereafter mostly add bulk to their trunk and limbs. They may live up to 250 years.

Indigenous people used an infusion of the twigs to treat fevers, an infusion of the bark to treat intestinal worms, and mashed the roots as a poultice for wounds. The wood was used to make canoe paddles, pipes, canes, tools, handles, and digging sticks, and the roots were woven into baskets. It was, and still is, often used as firewood, because it lights fairly easily. Folk wisdom has it that poisonous snakes will not cross an ash branch, and so it was sometimes used as the the bottom of a doorway, and leaves were packed into sandals as a snake repellent.

In June of this year a serious invasive pest of Oregon Ash (and ash trees in general) was found in Forest Grove, Oregon. The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis– often referred to as EAB) is a beautiful but extremely destructive jewel beetle (family Buprestidae) from Asia, that first appeared in North America in the Detroit area in 2002 (for a fuller and more depressing account of this species in North America see Herms/McCullough; 2013). The adults feed on the leaves of the ash, but do little damage. Unfortunately, and unlike most buprestids, EAB often lay eggs on healthy trees, and it’s the larvae that are the problem, because they feed on the phloem, disrupting the flow of water and nutrients. In small numbers they wouldn’t be a problem, but in the absence of their native predators and parasitoids, and because our ash trees haven’t evolved defenses (such as increased tannin) against these attacks (and for some reason seem not to recognize the attack, and thus fail to deploy the defenses they do have , such as a radical increase in sap production which could immobilize or even suffocate the larvae), their numbers can explode, and it’s thought that once a population has been attacked most trees will be dead or dying within 10 years.

But before you go out and start killing every bug you find on an ash tree (I know that most of my readers would never do such a thing, but there are many reactionary people out there who might stumble upon this site and get all gung-ho and vigilante about wiping out this ‘Asian menace’), I implore you to look at this illustration comparing EABs to the beneficial insects that have been confused with them, as well as these images of EABs from BugGuide. And even if you are fairly positive that you have found an EAB, do not kill it. Collect it, note the location as precisely as possible, and then report it to the Oregon Invasive Species online hotline, or the Washington Invasive Species Council. They will then positively identify your specimen, and initiate a response, if it is appropriate.

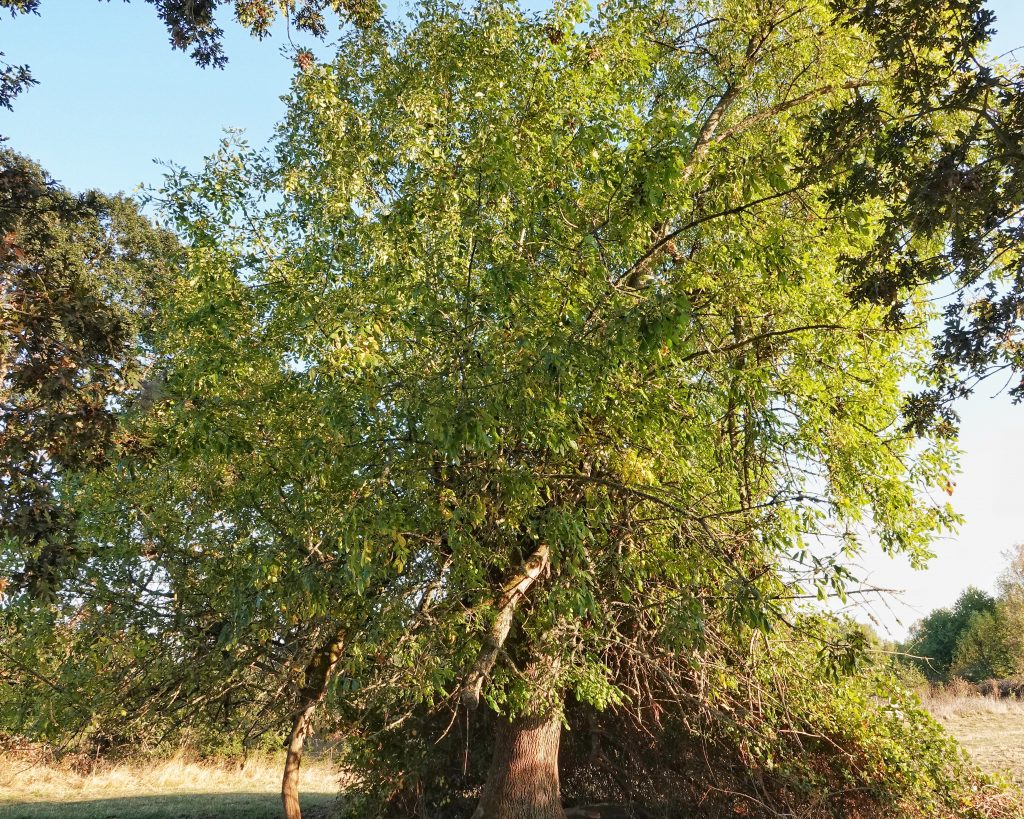

Description– Medium sized (up to 80’ tall, and 2.5’ DBH, which means diameter at breast height- this is where the diameter of trees is measured, because the base of a tree is usually wider, an important distinction with many wide trunked deciduous trees, though less so with most of the conifers I’ve been profiling) deciduous tree with compound leaves and brown bark that looks crosshatched or woven, resulting in narrow, elongated plates between the furrows, which are often curved around branches; leaves are compound, odd pinnate, and usually have 5-7 opposite leaflets, which are sessile, ovate, pointed, about twice as long as wide, and have alternating veins from a central midrib; flowers are small, green, in panicles that appear before the leaves; samaras are single winged; in crowded conditions the develop a narrow crown, but in the open they have a broad, curved crown.

Similar species-Oregon Ash is our only native tree with compound leaves. If you are unsure of how to tell compound leaves from simple leaves, look at the base of the petiole (leaf or leaflet stem). Simple leaves have a bud at the base of the petiole, while compound leaves do not have a bud at the base of the leaflet or leaflet petiole, though there is a bud at the base of the rachis (the stem from which the leaflets branch); the introduced Fraxinus pennsylvanica has petiolulate leaflets, is rare to uncommon, and is found east of the Cascades.

Habitat– Woodlands along rivers lakes, ponds, sloughs, and vernally wet areas; primarily found at low elevations but may be found at up to 3,000’ elevation in the Coast range

Range-Western North America;found west of the Cascades in our region, though mostly absent in Washington state except around the Columbia, Cowlitz, and Chehalis rivers, and the Puget Sound, and present in much of sw Oregon/nw California.

Reproductive timing– Flowers March-May, before the leaves appear; samaras mature in August-September; usually doesn’t begin producing seed until it’s about 30 years old; when relatively isolated it produces seed every year, but in denser stands it only produces seed every 3-5 years.

Eaten by– The Emerald Ash Borer, as discussed above; ash seed weevils (Lignyodes spp) eat the seeds, and can be a destructive pest; the bark beetles Hylesinus oregonus and H. californicus feed on the phloem, but are not considered to be a pest; the lace bug Leptoypha minor, the plant bug Tropidosteptes pacificus, the tree cricket Oecanthus fultoni, and stink bugs in Brochymena feed on the leaves and twigs; I couldn’t find anything specific to this tree for the leaf beetles, which is odd since there are at least a dozen species known to feed on ash trees; larval host for the swallowtail butterflies Papilio rutulus and P. multicaudata, and the moths Hyphantria cunea, Eupithecia maestosa, Operophtera danybi, Philtraea latifoliae, Tetracis jubararia, Egira hiemalis, Lithophane georgii, Sympistis fortis, Sphinx chersis, and Archips argyrospila, as well as the leaf mining moth Prays fraxinella and those in Marmara and Caloptilia; many species of aphids and fungi attack these trees; beaver and nutria feed on all parts of the tree (usually small trees or those felled by the beaver), many birds and squirrels feed on the seeds, and deer and elk browse the foliage; larvae of the longhorn beetles Brothylus conspersus and Phymatodes vulneratus feed on dead or dying trees, as does the powder post beetle Ptilinus basalis.

Etymology of names–Fraxinus is the Latin word for ash trees. The specific epithet latifolia is from the Latin words for ‘broad leaves’, since it has broader leaves than many ashes, although this species is not markedly broader leaved than F. americana or F. pennsylvanica. The common name ‘ash’ for this group traces back to the Old English word for these trees, which itself came from an Indo-European word for ‘spear’, a common medieval use for this wood.

Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia) | Oregon Wood Innovation Center

pests of fraxinus latifolia – Google Scholar

Oregon Ash, Fraxinus latifolia | Native Plants PNW

BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

Burke Herbarium Image Collection

Species Agrilus planipennis – Emerald Ash Borer – BugGuide.Net

Species Agrilus planipennis – Emerald Ash Borer – BugGuide.Net

https://extension.oregonstate.edu/eab

WISC – Washington Invasive Species Council