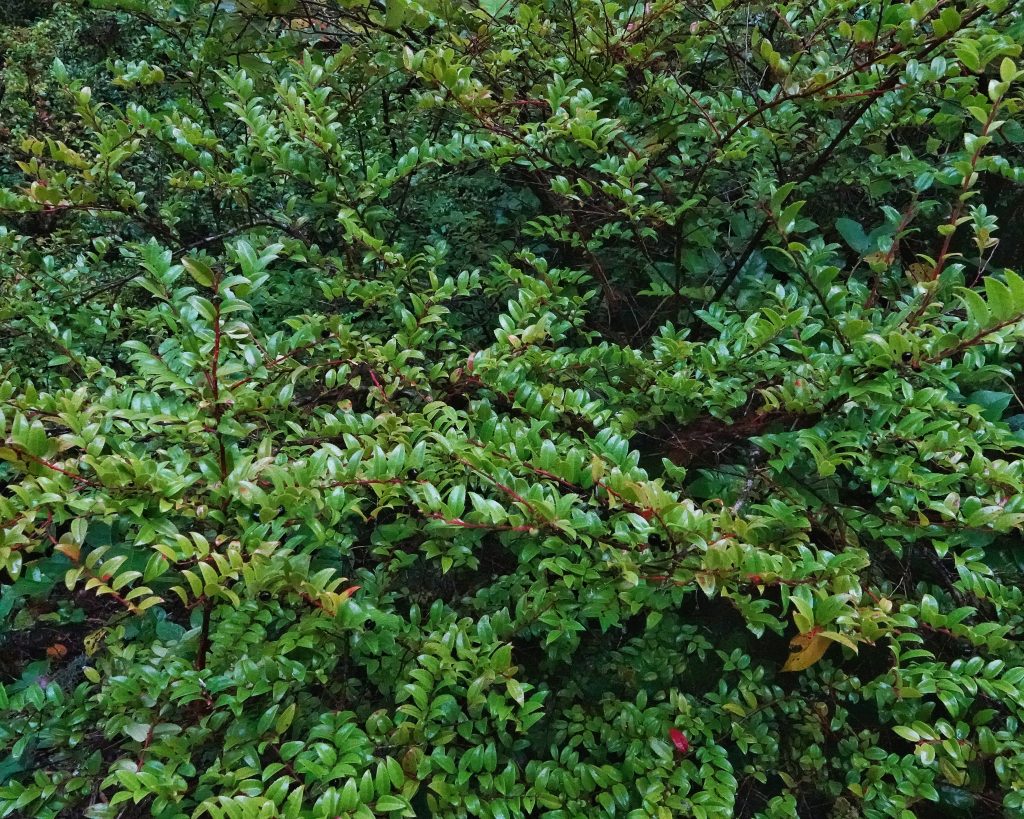

Anyone who has spent time in the coastal forests of our region has undoubtedly seen Vaccinium ovatum (which is also apparently known colloquially as winter huckleberry, cynamoka berry and California huckleberry, although I’ve never heard it referred to as anything but evergreen huckleberry by any non-botanist), which grows abundantly in those regions. Anecdotally I would say that this plant is only eclipsed by salal (both of which are members of the heath family, Ericaceae) in shrub abundance in conifer forests near the coast.

With its handsome, evergreen foliage, pretty flowers, attractive fruit, and wildlife attracting potential, it is no surprise that evergreen huckleberry is a popular plant for landscaping, and it was first introduced into cultivation by David Douglas in 1826. It is also used in restoration projects, and the foliage is much used by florists in arrangements. The berries were an important food source for coastal indigenous peoples, who ate them raw or dried, made them into jams, and baked them into pies and cakes, and they are used in these same ways by modern day foragers. A decoction of leaves was used to treat diabetes, and an infusion of leaves and sugar was given to post-partum mothers to help them regain their strength.

One of the many reasons that modern foragers value evergreen huckleberries is that in addition to calories, vitamin C, and other vitamins and minerals, they contain high levels of the secondary metabolites anthocyanins, and polyphenolics. In fact, as one study (Lee/Finn/Wrolstad; 2013) shows, they contain more of these health boosting metabolites than commercially harvested blueberries, or other wild blueberries, huckleberries, or whortleberries.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Colleen Rossier’s PhD dissertation, “Forests, Fire, and Food: Integrating Indigenous and Western Sciences to Revitalize Evergreen Huckleberries (Vaccinium ovatum) and Enhance Socio-Ecological Resilience in Collaboration with Karuk, Yurok, and Hupa People” (2019). I must admit I haven’t read the whole thing yet, because it’s well over 500 pages long, but I’ve read enough to see that she makes a very good case for the value of the knowledge of cultures that live amidst, and depend upon, such resources. What struck me the most is the way that these people understood what requirements a healthy and productive evergreen huckleberry bush has, how to bring that about, and where they are most likely to be located.

For example; “…higher quality and quantity V. ovatum patches are significantly correlated with 60% canopy closure, Northeast facing aspects, shorter distances to the nearest canopy gaps (<27m), lower altitude (<500m above sea-level), clay soils, and understory plant species richness. Combined litter and duff depth was negatively correlated while the number of large (>50cm DBH) tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) trees was positively correlated with HPQ [Huckleberry Patch Quality], though neither were significant.” This sort of knowledge requires an intimacy with the plant that western science is simply not often able to achieve because of limited time and resources, but that is second nature within cultures that have lived with them for centuries. And, possibly most compelling to me, was that these native peoples strive to enhance these resources for the benefit of the animals, as well as for that of the tribe.

Description-Medium sized (2-10’ tall) shrub with evergreen leaves that are in two rows, alternating, and have serrate margins; leaves are dark green above and lighter green and hairy below, egg-shaped to broadly lanceolate, with a pointed tip, leathery, 1-2” long, and form flat sprays; flowers are bell shaped, white to pink with red sepals, in clusters in leaf axils; fruits are usually purplish black, but sometimes reddish brown, 5-8mm in diameter, and sometimes have a pruinosity similar to blueberries.

Similar species-Other Vaccinium with evergreen leaves are much shorter, have much smaller leaves, are usually found in bogs, and are called cranberries; Paxistima myrsinites (Oregon boxwood) has opposite leaves that are smaller and usually lance-shaped.

Habitat– Maritime influenced conifer and mixed forests, under 2400’ elevation.

Range-Native to the Pacific coast of North America from BC to Mexico; native populations are usually very near the ocean from BC to the central Oregon coast, and in Southern California, but in Northern California and Mexico they may be 50 miles from the sea, and in southern Oregon they can be found up to 60 miles inland.

Eaten by-The leaf beetle Timarcha intricata; adults of the shield bug Elasmostethus interstinctus; larval host for the butterfly Echo Azure, as well as the moths Lotisma trigonana, Eulithis destinata, Neoalcis californiaria, Adelphagrotis stellaris, Phlogophora periculosa, Argyrotaenia franciscana, Eucalantica polita and the leaf miners Cameraria gaultheriella, and unspecified Marmara; the leaves are browsed by elk, and occasionally deer; robins and other thrush, waxwings, towhees, grouse, and other birds consume the berries, as do bears, chipmunks, squirrels, skunks, foxes, and other mammals.

Reproductive timing-Blooms March into July, fruits ripen in August-September, but often remain on the plant into December

Etymology of names–Vaccinium is from the Latin word for whortleberry, Vaccinium myrtillus. The specific epithet ovatum is from the Latin word for egg-shaped, and refers to the shape of the leaves.

Evergreen Huckleberry, Vaccinium ovatum | Native Plants PNW

BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/37108/PDF/2004JAgricFoodChem52_7039_7044.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5613902/

And evergreen huckleberry is one of the most common Vaccinium hosts for the fir-blueberry rust (Pucciniastrum goeppertianum), at least in southwestern British Columbia.

That’s interesting information, Andy! I wasn’t aware of that. I’ll keep an eye out for it. Thanks!

It wasn’t until a friend from India picked up a fallen leaf (and was amazed) from a big leaf maple on a trip to see Mt. Saint Helens many years that I realized once again, how special the world we take for granted or ignore, around us is. thank you

You are so right, Kim. Thanks for your appreciation!

Living on the coast, this one’s a real favorite of mine! Nice to see someone else appreciating it in spite of its ubiquity.

I have a friend near with about 10 acres near Oysterville, and they have even more evergreen huckleberry than they do salal, by a 2-1 margin! This is such a valuable plant!

I’ve only been to Vashon Island a handful of times but on one visit I was astounded to see 20 ft. tall specimens showing great vigor. At least that’s my honest recollection. To me a very much favored plant; I have many several but no big ones in north Seattle. Thank you for the post.

The last picture was the best! Love the tiny redwood cone.

Thanks, Cecilia! Glad you enjoyed it!

Evergreen huckleberry turns out to be a good plant for human yards. The question is: How good is the habitat we’re planting, by planting them? I’ve seen golden-crowned kinglets feeding on my urban evergreen huckleberries, so evidently there are small, soft arthopods there. I was very interested in your list of insects, especially lepidoptera hosted by evergreen huckleberries. But clicking on your reference sites, I couldn’t find the information. Please, where did you get your list?

There is a lot of searching that I do when trying to determine what eats a given plant, and some of it comes from books I own. But for leps I always check https://www.cnps-scv.org/images/handouts/CaliforniaPlantsforLepidoptera2014.pdf ; for stink bugs and their ilk (Pentatomiodea) I use https://www.ndsu.edu/pubweb/~rider/Pentatomoidea/Hosts/plant_records_byhost.htm ; for leaf beetles I check https://www.zin.ru/animalia/coleoptera/pdf/clark_ledoux_et_al_2004.pdf . I’m thinking about doing a blog on identification and research for the profiles and I’ll have a more complete list in that.