When I moved to Vancouver, Washington in the late 70s I occasionally went smelt ‘dipping’ with a high school friend and his dad, and these fish were so abundant that the first dip I ever made resulted in a net full of fish, which overflowed the 5 gallon bucket that was considered to be a limit by everyone I knew. Even though that full bucket probably weighed closer to forty pounds than the actual limit of 20, I don’t ever remember a game warden questioning the amount, as long as there was only one bucket per person. And, as near as I can remember, the season was open year around and one could take that limit every day for as long as the run lasted. Considering the vast number of people harvesting these fish, and the fact that they average about 5 to a pound, it is likely that well over a million fish per year were harvested just by recreational dippers, with an additional 10 million by commercial fisheries. To put that in perspective, the entire run for any given year has only topped 11 million three times since 2010, and has never exceeded 18.3 million fish.

These fish in the family Osmeridae (freshwater smelts) have many common names, including eulachon, oolichan, hooligan, candlefish, and fathom fish, although most folks in the PNW simply refer to them by the generic term smelt, since they are the only smelt species that runs upriver to spawn in our region. Many indigenous people called eulachon ‘salvation fish’ because the timing of the runs in mid to late winter often meant the difference between starvation and fulfilling nutrient needs. They are called candlefish because, due to the high fat content of the fish when engaged in their freshwater spawning runs, they could be strung on a wick and dried, and then burned like candles.

As a callow sportsman I didn’t bother to learn much more about those smelt than that they were anadromous, semelparous (dying after they spawn), they tasted good when smoked (although it seemed like a lot of work), and were said to be good sturgeon bait. I always happily donated my catch to my buddy’s dad, except for saving a few dozen fish to use as masking and attracting scent on my trapline. We always went dipping at night, and these were intensely social affairs, with many of the participants warding off the cold with hard liquor which was not offered to us youngsters, and they went against my introverted desire to experience nature and sport from a solitary vantage point, so I eventually quit going.

Presumably due to some combination of over harvest by humans, climate change impacting both freshwater habitat and offshore plankton populations, bycatch of eulachon in offshore shrimp fisheries, and dams and water diversions, the runs dropped off precipitously in the 90s, and by 2010 the fish in the Southern DPS (Distinct Population Segment; these fish run into rivers from, and including, the Skeena River drainage in BC to, and including, those spawning in the Mad River in California) had been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, effectively shutting down any legal harvest within that area.

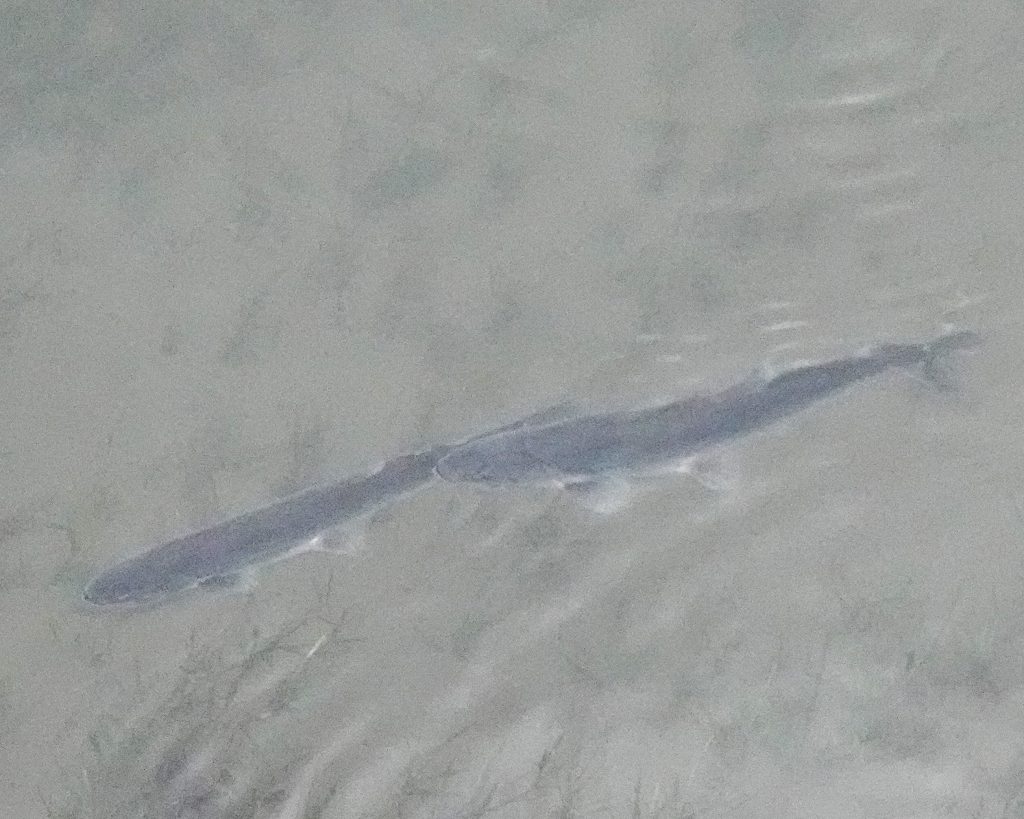

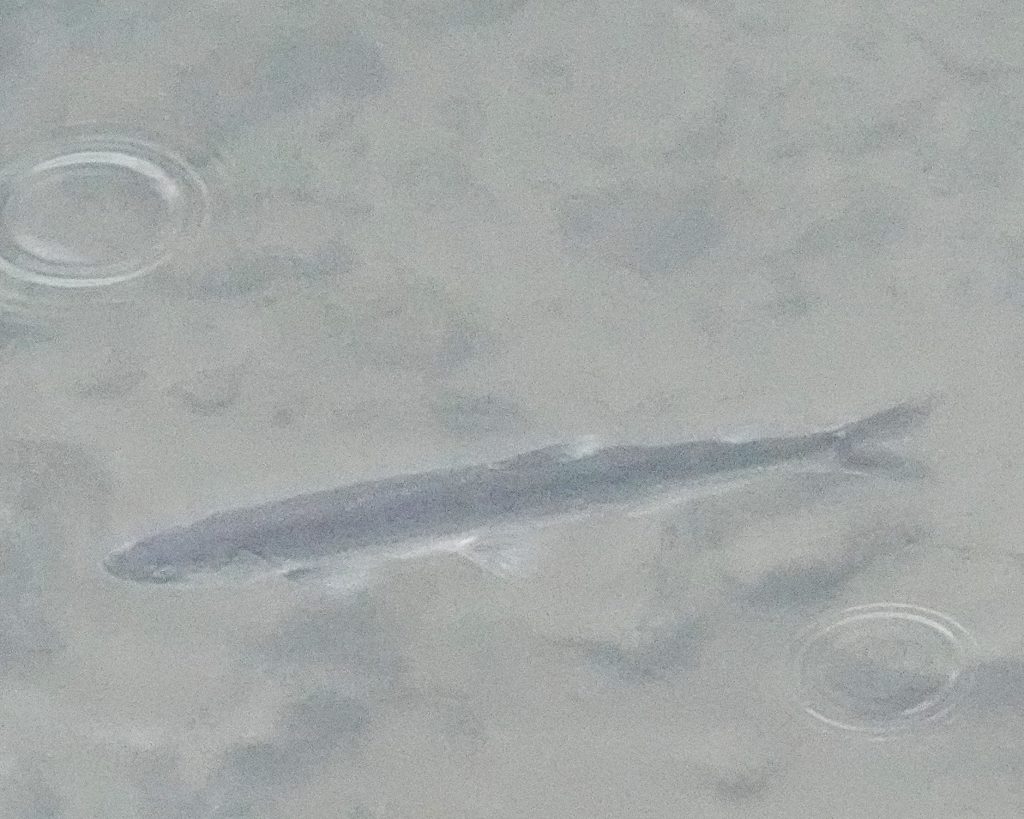

Working in the Longview/Kelso area in late January of 2014, killing time between rides in my job driving medical transportation and with the relatively more mature hobby of being a recreational naturalist, I was attracted to the banks of the Cowlitz River by the barking of sea lions and a plethora of birds wheeling through the air. What I found there was a column at least 2’ in diameter of densely packed eulachon moving upriver about 5’ from shore! I didn’t remember ever seeing them in daylight before, and I was spellbound by the sight, to the point where I actually forgot I was working and ended up being late to my next client.

Over the next several weeks I would usually head to the Cowlitz River when I had time to spare, just to watch the spectacle wrought by the return of these fish, and I would often sit in wonder that all of the things we see as discrete entities or objects, from smelt to people to English daisies to concrete to dirt to rivers to bacteria to molecules, do not exist separately from the rest of the world. Their existence is not as individuals or objects, but is a relationship to each other, and those untold relationships are what make up the world. And though we may see some part of that relationship, e.g, that smelt feed birds, sea lions, and sturgeon, and their post spawning corpses feed microorganisms that in turn feed their progeny, we do not know, and possibly cannot know, the complete web of their interrelationships, or the myriad ways in which a single smelt is vital to the functioning of the world as it presently exists.

That was the first year after the ESA listing that dipping for smelt was allowed on the Cowlitz, though the limit was only 10 pounds and the fishery was only open on Saturday mornings from February 8-March 8. These openings were so popular that I would drive about 6 miles out of my way on Saturdays to avoid the traffic they engendered on the Westside Hwy, a road I drove regularly when transporting people from a particular nursing home to their dialysis appointments. Since then there haven’t been nearly that many openings in a given year, and there was no harvest at all in 2018-19 because of low numbers of returning fish, which seems to correspond to a couple of previous El Niño (an ocean currents pattern that brings warmer Pacific Ocean waters into the north) years, which not only depresses the stocks of copepods and other plankton on which the fish feed, but brings an increased interest from predators because of their limited options, and brings more predators in general who are following the warmer water.

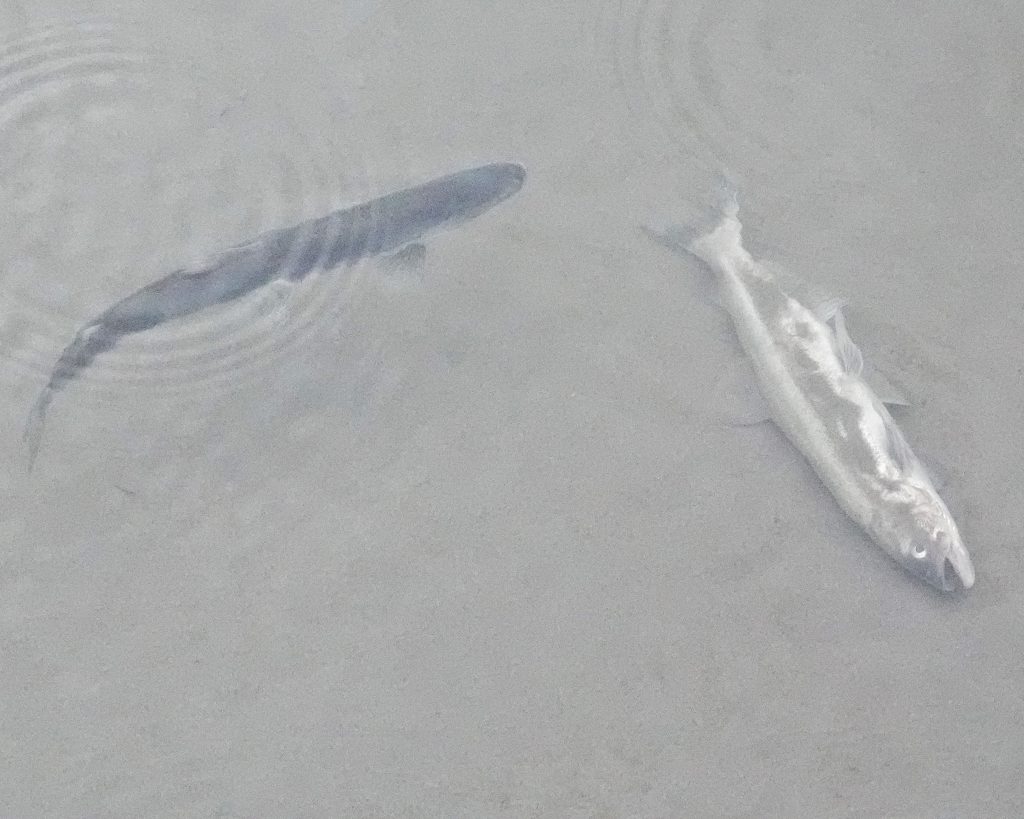

On a recent walk with my nbo Morgan we visited the Cowlitz because I was curious about whether there would be smelt. I didn’t have my hopes up because there didn’t seem to be many birds around (a couple immature gulls and a few common mergansers) and no sea lions, but as soon as I got near the rivers edge I could see small groups of eulachon swimming upstream, as well as a fair number of dead ones on shore. As I mentioned above, eulachon die after spawning (not surprising since they do not feed on their spawning runs, although American shad and steelhead also do not feed on their upstream spawning runs and some of them live through the experience), but I’m not used to seeing dead ones on the banks, which I had always attributed to the scavenging of birds and sea lions. Plus I had always assumed that they spawned far upriver from where I observed them on the lower Cowlitz River. But I was puzzled by the lack of sea lions and birds, and since I hadn’t heard of an opening on the Cowlitz this year I wondered whether this was the very beginning, or nearing the end of the run, since the timing varies from year to year.

So I took a flier and called the Region 5 office of the WDFW, where I was directed to Laura Heironimus, who is the lead for WDFW’s Sturgeon, Smelt, and Lamprey Unit (as well as a co-author of the ‘Washington and Oregon Eulachon Management Plan; 2nd edition’; 2023, and a number of other smelt studies such as this and this). She was doing field research at the time, but was gracious enough to respond the next day to the message I had left, as well as to an email I subsequently sent her. It turns out that I was grossly mistaken in thinking that eulachon spawned far upstream. According to Laura they may spawn anywhere they find suitable conditions during their upstream migration, including in the main stem of the Lower Columbia. So it is possible to find spawned out and dying or dead fish anywhere along their route. She also pointed out that water releases from the dams on the upper Cowltz can fluctuate, stranding dead and dying fish that were in the shallows when the water level dropped.

She told me that birds and sea lions were moving into the Cowlitz, but that there were still large numbers of them in the Columbia River, because the bulk of the smelt run hadn’t moved into the tributaries yet (tributaries of the Columbia that have smelt runs include Grays River, the Cowlitz, Kalama, and N.F. Lewis rivers on the Washington side, and the Sandy River in Oregon). Eulachon appear to prefer to run in water that is over 39.2⁰F (4⁰C), and the rivers have been above that all winter (although not by much- the water temperature the day we were there appears to have been about 43⁰F) so small numbers of fish have been moving into the tributaries for a few weeks. But the timing is also influenced by turbidity (water clarity), because the fish feel safer from predators in water with less visibility, and there was at least 3-6’ of visibility on the Cowlitz the day we were there, which is pretty clear water for that river at that time of year. Laura also mentioned that eulachon have a decided preference for moving into rivers under the cover of darkness.

As I mentioned, eulachon are anadromous, but they spend about 95% of their lives in salt water. Almost immediately after hatching the larvae begin drifting downstream, eventually settling in the estuary near the mouth of their natal river system. After adjusting to the saline conditions and growing to about 30mm, larvae morph into juveniles, which soon head to the open ocean in schools, and congregate near the sea floor along the Continental Shelf in water 50-600’ deep. When they are between 2 and 3 years old they become sexually mature, and that winter they migrate back into their natal river systems to spawn, with the males leading the charge. It is interesting to note that they seem to key on their natal estuary, and move through it into freshwater, but, unlike salmonids, they do not display faithfulness to their natal river, although the mechanism by which they choose their spawning grounds is unknown.

Eulachon eggs have a double membrane, and after fertilization the outer layer ruptures to form an adhesive surface which often attaches to some portion of the substrate. But, according to “Eulachon: A Review Of Biology And An Annotated Bibliography” ( Wilson et al.; 2006)https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/8587/noaa_8587_DS1.pdf, there is a trade off, in that being anchored appears to lead to higher mortality amongst the eggs as opposed to being free floating. However salinity greatly influences survival of the eggs, with levels higher than 16 parts per thousand being lethal, so that in the lower portions of a river the benefits of anchoring to remain outside those saline percentages would outweigh the predation risks of remaining in one spot. Wilson et al.’s paper was also quite interesting for the contradictions and conflicting data sets it presented, showing just how rudimentary our knowledge actually is of eulachon biology and life history.

As might be expected from something called ‘salvation fish’ by some tribes, eulachon were culturally important to many indigenous peoples, ceremonially, nutritionally, practically, and medicinally. Beyond the facts that these fish arrived at a critical juncture in the food harvest vs. food consumption cycle for the year, and that they inspired ceremonial feasts (the Nisga’a tribe in central BC considered the arrival of eulachon to be the start of the new year, initiating a festival called Hoobiyee), the fish are a storehouse of vital nutrients, including omega-3 fatty acids, Vitamins A, E, and K,protein, and iron. But arguably the most important use of these fish was for their oil, which was simply called grease.

There were various techniques for rendering the grease, but almost all of them involved letting the fish decompose for a few to several days in a contained area, and then using boiling water to separate the grease from the fish, and ladling the congealed grease from the surface of the water. This highly nutritious grease was used as a condiment similar to butter by almost every tribe in the PNW, as well as being used medicinally to treat skin ailments and intestinal disorders. It was so valuable that extensive trade routes, called grease trails, developed between interior and coastal tribes, and it was a mainstay of intertribal trade economies.

It is heartening to see that eulachon are making some kind of a comeback, although I found it very distressing to read that even after their numbers began to plummet and tribal officials began calling for a listing under the ESA, Oregon wildlife officials imposed almost no additional restrictions on the harvest of these fish. WDFW was quicker to get on board and shortened seasons and lowered bag limits as early as 1998. One of the many benefits of the 2010 listing of eulachon as threatened is that it freed up federal money to study these fish. But the incremental increase in the numbers of these fish even after strictly regulating their harvest shows that many, if not most, of the dangers that their recovery faces lie in the ocean, and with accelerating climate change, El Niño events pushing warmer water northward, and a multitude of variables which we still do not understand, it seems that the populations of these fish in California, Oregon, Washington, and southern BC, which are a critical element in the lives of so many organisms in the PNW, are still on the cusp of oblivion.

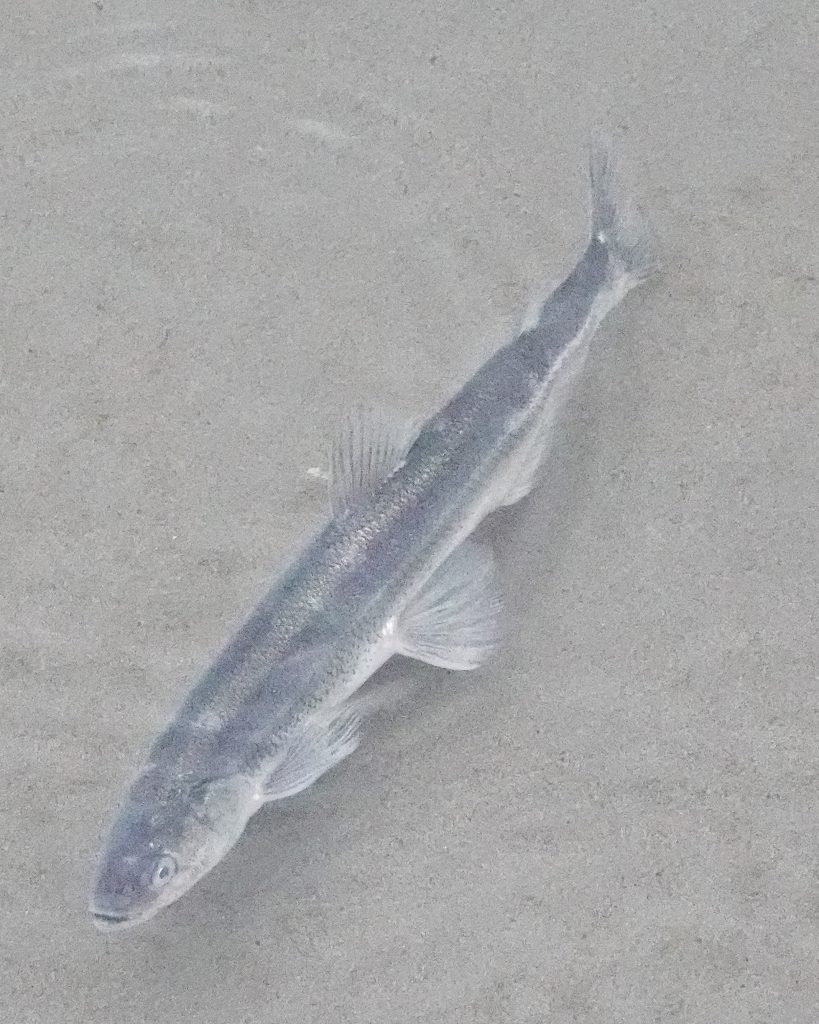

Description-Small (6-10” in length) anadromous fish that are blue to dark grey above and silver below, with an obvious adipose fin, a forked tail, and an anal fin that reaches almost to the tail; they are narrow side to side and quite streamlined in shape; spawning males have rougher skin than females, due to tubercles on their scales, and have a lateral ridge that females lack.

Similar species-Trout/char are more colorful, usually have spots, are thicker side to side and more oval in shape, and their anal fin extends only a short ways towards the tail; sardines and other members of the herring family lack adipose fins.

Habitat-Larvae and early juveniles are found in estuaries, with older juveniles and pre-spawning adults found in the open ocean along the continental shelf in 50-600’ of water; it seems that freshwater spawning takes place primarily in river systems that end in extensive estuaries, such as that of the Columbia River, and those waters culminating in Coos Bay, Winchester Bay, Willapa Bay, and Grays Harbor, amongst others. ETA- I have been informed by retired WDFW biologist Olaf Langness that eulachon do spawn in some coastal river systems that do not have significant estuaries.

Range– Near shore areas of the northeast Pacific Ocean from Monterey Bay north to the southeast Bering Sea; spawn in rivers from the Cook Inlet in Alaska to the Mad River in California; historically both freshwater and saltwater distribution extended southward to Baja California, but the fish have been extirpated from south of Monterey Bay.

Eats-Adults do not feed in freshwater; larvae and juveniles feed on planktonic crustaceans, especially copepods; adults feed on cumaceans, copepods, and especially krill (euphausiids); unlike many plankton and the animals that feed on them, they do not engage in diel vertical migration, which means they do not move towards the waters surface after dark.

Eaten by– Carnivores of all classes, including loons, grebes, cormorants, mergansers, gulls, otters, sea lions, seals, sturgeon, salmon, marine fishes, and probably anything else that can catch them; spawned out corpses are scavenged by various birds and mammals.

Adults active– Year around, but only found in freshwater in mid to late winter.

Life cycle– May be sexually mature at 2 years old, but usually spawn when they are 3; males usually are the first to begin the spawning run; eggs and milt are broadcast over areas of sand and coarse gravel; females release 7,000-60,000 eggs; outer membrane of the eggs ruptures and becomes adhesive after fertilization, and the eggs hatch in 3-8 weeks, depending on the temperature; larvae (4-8mm long) are carried downstream to estuaries by river flow; juveniles disperse to the open ocean within a year of hatching, where they live near the sea floor of the continental shelf in 50-600’ of water; almost always die after spawning, but occasionally, though quite rarely, may survive to spawn again

Etymology of names–Thaleichthys appears to be from the Greek words for ‘luxurious/rich’ and ‘fish’, and probably refers to the sheer abundance of the smelts on their spawning runs, although there are some who think it refers the the oil laden richness of their flesh. The specific epithet pacificus refers to the Pacific Ocean, in which they spend the majority of the lives.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/eulachon

https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=34431

http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=eulachon.printerfriendly

https://www.fishbase.se/summary/thaleichthys-pacificus.html

What is an “oolichan?” | Office for Science and Society – McGill University

Oolichan… more than just a fish – WWF.CA

The Saviour Fish: Protecting Nisga’a Connection to Oolichan | Coast Funds

Smelt runs rebound, but don’t grab that net yet | KATU

https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2023-01/draft-plan-draft-2023-eulachon-management-plan.pdf

https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/02180/wdfw02180.pdf

Prospects good for at least 1 Cowlitz River smelt dip – The Columbian

Q&A With WDFW’s Smelt Biologist –

https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/8587/noaa_8587_DS1.pdf

https://sci.bban.top/pdf/10.1139/f64-112.pdf?download=true

Dan, what a fantastic profile! Thank you. I especially appreciate when you are able to weave in personal and local history, what the colloquial names and approaches to these animals are, how they fit into the seasonal cycle. Just such valuable transfer of knowledge. Chris

Thank you so much, Chris! I’m really glad you enjoyed it!

I so enjoyed this profile to start my day, a fascinating read! I second Chris’s thoughts about the added dimension personal and local history provides.

Thank you for your appreciation, Karen!

I would like to point out that Eulachon are not the only smelt in our region. There are several species, mostly restricted to the ocean and lower estuaries, but there is the Longfin smelt that does spawn above the estuary boundary, at a similar time as Eulachon. Their larvae are near impossible to distinguish without doing genetic testing. Fortunately, these larvae only overlap with the Eulachon for the early outmigration in some years, so corrections to the spawning stock biomass for the Columbia River and Chehalis River were considered unnecessary.

Also, to my knowledge there was no evidence that these feeble 7-9 mm larvae had the capacity to fight the Columbia River flow. It is estimated that they get flushed out in the Columbia River plume, buttoning up (egg sac absorbed) about that time, hence beginning endogenous feeding in marine waters. Perhaps new studies (since mid 2020) support the rearing in the estuary hypothesis, but I would be surprised. Eulachon spawn in various coastal watersheds, and many of those have insignificant estuaries.

You may well be correct, Olaf, about all of the things you say, but that wasn’t the information that I found. But as far as the estuary of the Columbia, on an incoming tide even weak swimming larvae would be able to move to the slack water on the margins. And I did say that the juveniles soon head for the sea. However I did mean to say that they were the only smelt in our region to run upriver, and I amended the profile to reflect this.

Before I retired, we were wanting to better understand to what extent some or all larvae may become estuary residents or in some way delayed by incoming tides before flushing out in the plume. Funding such research was an issue at the time, especially given what was known from water particle travel studies and the passive migration of the minuscule Eulachon larvae. It has been three years, so maybe that has been explored by Dr. Jeannette Zamon or her colleagues at the NMFS Point Adams Research Station in Hammond, Oregon.

It is always a concern for me as to whether I’m finding accurate information, since I am neither an expert on anything, nor educated in the fields which I’m interested in. I just gather what I can find in a reasonable amount of time, and summarize it to the best of my ability, and put it out there. My primary goal is not to write a treatise, but to spark appreciation and pique interest. Thanks for your comments, Olaf!

I also amended the post to say you had told me that they do spawn in coastal rivers without significant estuaries. What was your post with Fish and Game?

I worked the last 20 years at WDFW in the Sturgeon and Smelt unit as the Fish and Wildlife Biologist 3. Given my experience with ESA salmon species (analytical analysis of the removal of Snake River dams, etc.), I tended to be the agency contact for the listed Green Sturgeon and Eulachon (serving on various federal recovery teams). It was a rewarding experience, and proud to say my daughter followed in my footsteps and is currently a FWB3 for WDFW working on pollution issues in Puget Sound.

Sounds like a cool job! Thanks, Olaf!

Thank you Dan, I enjoyed your information. I too have similar memories of this fish in Northern California with the beach covered with fish and my family using nets between two large poles to dip into the incoming waves to fill buckets. I have spent time on the Mad River and didn’t know then the connection it had with this little fish.

Sounds like a fun time, Teri! Thanks for your appreciation!

Thanks for this profile, our son is a sturgeon and smelt researcher for the WDF&W in Region 5. I grew up eating smelt as did he. There used to be a run of them in the Washougal River before Highway 14 was built crossing Lady Island on a causeway on the east end of the island changing where the flow of the river went into the Columbia River.

I remember people saying there used to be smelt in the Washougal, but I never knew why they disappeared. Thanks for the info, Wilson!

This is my favorite profile of yours yet–such a great blend of story and information, past, present–and potential future. I admit I didn’t know as much about these fish as the salmon, but this helped fill in some blanks.