I decided to write this blog because, at only 558 species, it is quite likely that many folks will find organisms that are not covered here, and I wanted to delineate the process whereby I go from a sighting of an unknown organism to the information in a profile, so that people can discover these things for themselves in the absence of an extant profile on this site.

First and foremost, one must identify the organism in question, which means either having the specimen in hand, with some sort of magnification available, or really good photos of salient details. I am often surprised at the blurry and/or uncropped photos people post on Facebook, and then they expect someone to be able to identify a fuzzy dot, though I am frankly amazed that some experts are actually able to discern enough information from those photos to offer an identification. However, poor photos are just not going to get it done if you don’t already know what species it is. Since almost everyone nowadays has a camera on their phone, that is a good first option, but a bit of practice is necessary. Before I got my first Olympus TG 5 I took literally thousands of photos with my iPhone, and at first many of those were of small, inanimate objects, so I could get a feel for how to make them turn out well, without the pressure of a interesting/spectacular bug that was going to get away. Then I ran them through the editing app that came with the phone, first cropping them so that the object filled most of the screen, then experimenting with light, contrast, sharpening, and coloration, until details became clear. The photo editing app on the phone has improved, though I now use Snapseed, because it allows me to apply a suite of edits to a string of photos. For me it wasn’t a quick process learning to take good photos of small objects on my phone, but photography for its own sake can be quite rewarding. With practice one can get good resolution photos with an unadorned camera phone of objects as small as 3/8” (9mm). For anything smaller than that you’ll need to either get a macro lens that can be fitted to the phone, or buy a camera with macro settings. I chose the Olympus TG 5 because it has in-camera focus stacking which significantly increased the depth of field for my shots.

There is also the option of bringing the specimen home, although I almost always at least try to get in situ photographs. As I’ve mentioned before, refrigerating invertebrates (I bought a mini-fridge specifically for this purpose) for an hour or more will usually make them quite quiescent, allowing one to get good photographs from various angles. I try to get dorsal, ventral, lateral, and head on photos at a bare minimum. The refrigeration does not harm them as long as they are not frozen, and they can be released once they’ve been identified. Even when it comes to fungi and plants I try to grab a specimen and take it home, both because I can get better photographs in the controlled setting of my study, and because it disrupts the flow of a hike, not to mention greatly irritating your hiking partner if their interests don’t coincide, to break out the books and hand lens and go through the steps needed to positively identify the moss, lichen, or flowering plant in question. Which isn’t to say that I don’t carry and consult various field guides when I’m out and about, especially when I’m camping as opposed to being on a day hike. It’s just that I only use them for preliminary identification, something to get me in the ballpark, and I don’t pack around diagnostic tomes, although I do keep a beat up copy of the first edition of Hitchcock’s Flora of the Pacific Northwest in my van at all times. Although it is best for long term storage to dry and/or press plants, for immediate identification purposes it is best to put them in a slightly damp ziplock bag so they don’t dry out, and do the identification process as soon as possible after getting home, and to refrigerate them if there will be a delay. Even with refrigeration they will mold and wilt in just a day or two. If you will be relying on in situ photographs be sure to get photos of the top and bottom of the leaves, the stem with a focus on leaf axils, and the flowers with views from multiple angles, as well as of the whole plant.

Now that you have these clear photos of the whole organism and it’s salient details you can start the identification process. If you have field guides or other identification books, and you have an idea about what family it’s in, you can start paging through those species to see if you find something that looks right. You can also plug the photos into one of the free identification apps that are available. For general purposes I use the Seek app, available by itself or through iNaturalist. Some folks use Google Lens on the Google home page, and I’ve had some success with that, but it doesn’t seem as complete as the Seek app for invertebrates and wild plants, though it’s at least as good when it comes to vertebrates and ornamental plants, so I often try both. There is also fieldguide.ai, which has a general identification aspect, though I use it primarily for the part dedicated to identifying lepidoptera. There are others as well, but the thing you need to remember is that, as great a tool as these apps are, they are highly fallible and getting identification options from them is just the first step. You have to verify it. And how hard you may have to work at that depends on your answer to the question- ‘How precise does this identification need to be?’

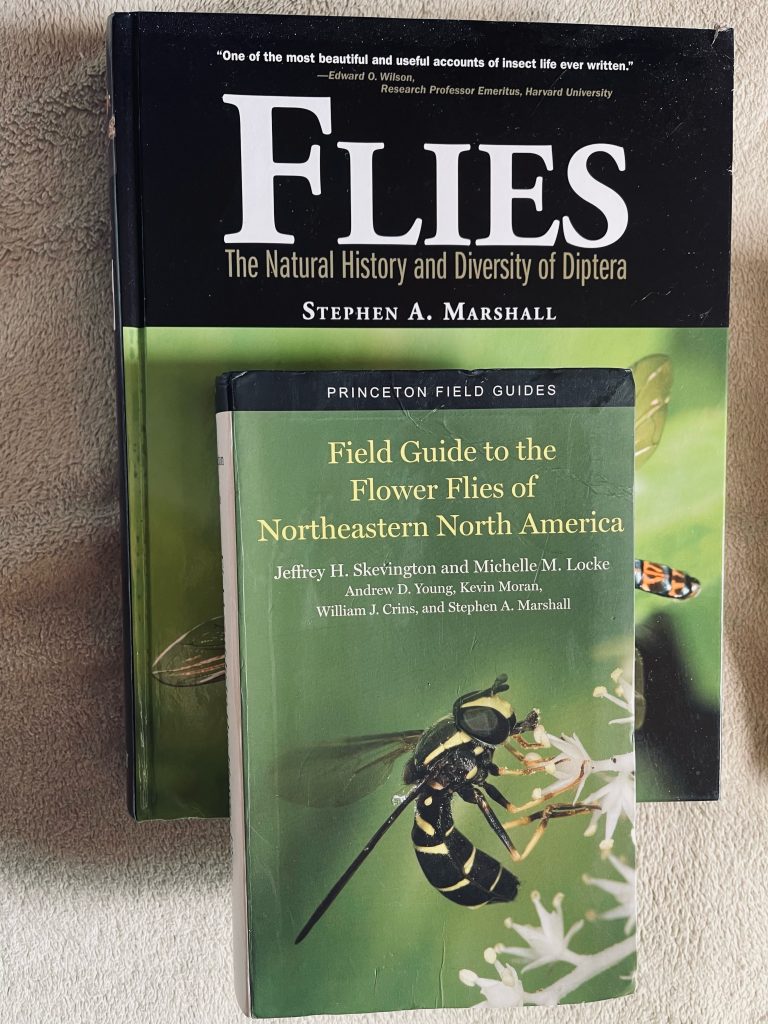

If you’re satisfied to know that that flower is a shooting star in the genus Dodecatheon, that will be fairly simple to verify. But if you want to know which of the 9 shooting stars we have in this region it is, you’ll need to do some digging, and if you want to verify that it is Dodecatheon pulchellum you will probably have to dig deep, since its range overlaps every other shooting star in this region. Even before starting this website I liked to try to get things to species, and it’s even more important to me now, although I have learned that sometimes settling for knowing the genus is good for my sanity. I love books, and have a variety of identification manuals, but if you prefer to do things online Oregon Flora is a great place to start comparing the options you got on the identification app if it’s a plant you’re trying to identify, and BugGuide is the place to start if you have a bug.

For me the importance of identifying something to the species level lies in the fact that you can’t really understand, or even research, the relationships between an organism and its environment unless you know what species it is. In reality a species is just a concept, which is defined by its interrelationships with soil, moisture, and all of the rest of the organisms in its ecosystem. And but, to consistently identify organisms to the species level, at least when it comes to arthropods, fungi, and many plants, magnification and a good key is going to be required. Which means that one is often going to have to kill the bug or pick the flower, since it is problematic to carry a microscope into the woods and fields, and most bugs will not put up with examining their genitalia unless they have been euthanized.

Keying things out (the process of going through a dichotomous key and, based on which half of a couplet of questions best fits the specimen in hand, moving through the sections until you reach a probable species identification) can be tedious, or it can be fun, and is usually both, depending on how well one can see and define a given characteristic, and how many times one has to refer back to a glossary to try to figure out exactly what one is looking for, which for me is often dozens. But it is always fascinating to look through a stereoscope/microscope and find these delicate little structures magnified to the point where one can really see them in all their glory. I usually spend far more time geeking out on the details and sheer beauty revealed by the ‘scope, than I do on actually trying to figure out which couplet will send me in the right direction.

One trick to use when trying to key things from family to genus, or genus to species, is to try to find photos and range descriptions for the other possibilities, so you can eliminate some choices as you go through the key. You can’t always trust the identification of photos one finds on the internet, but there are very few organisms that one cannot find some sort of illustration for. Google scholar is an amateur’s best friend in finding keys, though access is often a problem. But Sci-Hub is a great resource for gaining access to dichotomous keys and scientific papers that are beyond a paywall. Just copy and paste the url or doi into their search box, and, in most cases, you will be able to find the resource.

I know that many, maybe most, of the people reading this will not be inclined to go through all of these processes. And that is okay! The simplest, least time consuming, and possibly most fun (although I really can’t stress enough just how incredibly cool things look through a microscope!) (and I also can’t stress enough how cool owning field guides can be, which can be operated without electricity or an internet connection, and which can be browsed at one’s leisure when being out in the field is not possible) process is to get a good, clear, well cropped photo, run it through a quality identification app, and then do a Google, Google Scholar, Bing, and Ecosia etc search and see what turns up. Compare your specimen to other species. Read the information on whatever you find. And, most importantly, try to open your mind to the relationships that the living organism you have found has with all of the other living organisms with which it interacts.

General identification apps

https://www.appurse.com/org.inaturalist.seek.html

Plant resources

Wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest

https://www.burkemuseum.org/collections-and-research/collections-databases

Flora of North America

BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

Plants for a Future

Silvics of North America, volume 1; Conifers

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/vol1_table_of_contents.htm

Silvics of North America, volume 2; Hardwoods

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/silvics_v2.pdf

Arthropod resources

Pentatomidae

Plant Host Records List by Host Species

Chrysomelidae hosts

https://www.zin.ru/animalia/coleoptera/pdf/clark_ledoux_et_al_2004.pdf

Lepidoptera hosts

https://www.cnps-scv.org/images/handouts/CaliforniaPlantsforLepidoptera2014.pdf

Well done! It gives us an idea of your meticulous process.

Thanks, Michael!

You bum! Elegantly and thoroughly presented, as always.

Thanks, Brooke!

This is so fabulous. I finally re-read it all at a more leisurely pace and it’s full of so much info. Thanks! I’ll bookmark this post for the next time I see something I don’t know (which is often!). Thanks for all the work you do to make this one of the best places on the internet.

Thank you so much for saying all of that, Bonnie Rae! Really glad to hear you found it useful! And thanks for your kudos on the site!

I have been enjoying your blog for quite some time. I love what you are doing. And this resource list is amazing. Being curious about our world is so important. Thank you for helping is all learn about what surrounds us in the lovely part of the universe we call home.

Thank you so much for your kind words and your appreciation, Julie! Glad you are enjoying this site!

Great post, thanks Dan. Are you happy with the Olympus camera?

Very happy, Chris! I own 3 of them. They make me look like a much better photographer than I really am. 😀Thanks for your appreciation!