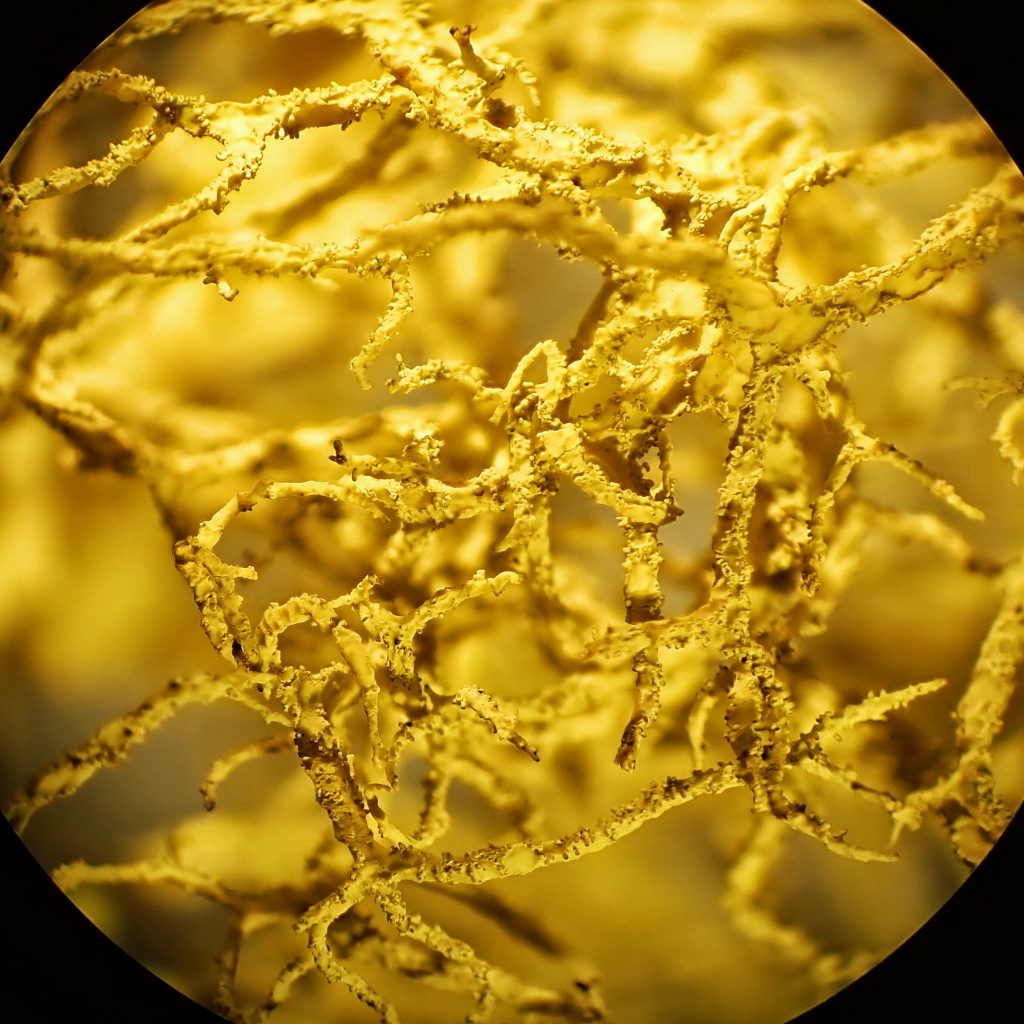

This is the other yellow/chartreuse, vulpinic acid producing lichen I found near Catherine Creek. I had been positive that it was Letharia vulpina when I first spotted it, but in doing research for this post I came across a paper which presented compelling evidence for splitting it into L. vulpina (Wolf Lichen) and L. lupina (Mountain Wolf Lichen), based on which clade of the algal partner Trebouxia jamesii they utilize as a photobiont. However it appears that they can’t be consistently differentiated by morphology. Thus one must identify the algal photobiont, and that is way beyond my capabilities. So we’ll have to call this Letharia vulpina complex, or maybe Letharia vulpina sensu lato (sensu lato means ‘in the broad sense’, and includes all associated taxa).

Another thing I learned in researching this post is that researchers have found an additional species of yeast that is always present in the cortex of Letharia spp. That makes 3 fungal components and an algal one, so far. Who knows what else they’ll find. Apparently it doesn’t take a village to raise a lichen; it takes a village to be a lichen.

Lichen in the L. vulpina complex tend to reproduce asexually (although it gets even more complicated because the fungal lineages that produce Letharia vulpina and L. lupina both come from evolutionary branching of Letharia columbiana, which usually reproduces sexually via spores formed in apothecia; L. vulpina and L. lupina seldom develop apothecia). They do this by producing vegetative propagules capable of germinating and forming a genetic clone of the plant.

There are two types of these propagules. Soredia are minute, powdery propagules which consist of a few strands of hyphae surrounding a cell of the algal photobiont. Isidia are larger and usually are composed of extrusions of cortical fungal tissue surrounding multiple cells of the photobiont. Soredia are usually disbursed by wind and rain, whereas isidia are more often broken off by some sort of physical interaction, such as animals or limbs brushing against the lichen. Isidia which are not dislodged have the added benefit of increasing the surface area of the lichen, thereby increasing the amount of photosynthesis which can occur.

One of the morphological differences in populations of Letharia vulpina sensu lato which Trevor Goward noticed, and that led him to wonder if there might be separate species, was that one group, which seems to fall into the L. vulpina category, had a much higher production of isidia, whereas the other, which appear to be L. lupina, had a much higher proportion of soredia production. But there is much intergrading of these characteristics, especially where they occur together (are sympatric).

Regardless of which Wolf Lichen is pictured here (and it may be both; the middle Columbia River Gorge appears to be an overlap area), they are a welcome sight, their bright chartreuse adding a festive ambiance to the dark earth tones of wintertime Ponderosa Pines and old fencing.

Description– Coral-like, bushy growth structure (fruticose), usually a vivid lemon yellow to chartreuse in healthy specimens; usually in small (up to tennis ball sized) clumps, but the clumps often aggregate to cover entire branches of trees; usually well represented with isidia and/or soredia; seldom have apothecia.

Similar species– Species in this complex cannot reliably be differentiated without molecular analysis; Letharia columbiana and L. gracilis usually have apothecia, and lack isidia and soredia. In our region there is nothing outside of the genus Letharia that is fruticose and yellow/chartreuse.

Habitat– On barkless (decorticate) branches, twigs and trunks of living, or especially on dead, pines and other conifers. Also common on fence boards. Uncommon to occasional on deciduous trees. Even rarer on rock. From low to mid elevations in open forests, or dryer microclimates of denser forests.

Range– Region wide, but much more common east of the Cascades.

Eaten by– Nothing with any sense. Contains the toxin vulpinic acid, which was used to kill wolves as well as foxes, although it’s possible that the ground glass it was mixed with was as responsible for their death as the Letharia. It does have known insecticidal, as well as insect repellent, qualities. Native Americans used it to make a yellow dye. It’s a popular addition to some types of bouquets and flower arrangements, and some populations have been decimated by the floral trade.

Etymology of names– Letharia is from the Latin for ‘very deadly’, in reference to the toxicity of vulpinic acid. The species epithets vulpina and lupina refer to foxes and wolves respectively, the most common animals that it has been used to poison.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letharia_vulpina

https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/not-one–not-two–but-three-fungi-present-in-lichen-65333

https://www.waysofenlichenment.net/public/susi_alterman_thesis.pdf

Quite informative! ☺️

It is amazing to me that scientists have figured out a much as they have about such complex yet not particularly “prestigious” organisms!