This appealing myxo in the family Stemonitaceae (order Stemonitales, although there appears to be movement towards changing that back to Stemonitidales, which was apparently misspelled by McBride in his seminal work on myxos in 1899) is sometimes called by the wonderfully evocative common name ‘chocolate tube slime’. However the closely related and very similar Stemonitis axifera also gets labeled that, so it’s not particularly useful for differentiation, which is, after all, the purpose of a label. Stemonitis fusca may be the most widely distributed myxo in the world, being found everywhere there is wood on all of the continents except Antarctica.

Stemonitis fusca can be found at many different levels in wooded areas, from logs on the ground to the canopy. They can even tolerate high levels of salinity, as evidenced by their presence in mangrove swamps. Though their spores are not as small as those of their cousins S. axifera and S. smithii, they are still relatively small compared to, say, Lamproderma sp. or Trichia varia. This helps with their dispersal ability, since small spores are more easily moved by wind and remain aloft for longer periods. It is thought that the long stalks also help with spore dispersal, although the colony I found were all hanging down within a hollow on the underside of a rotten log.

They are also dispersed by the multitude of creatures that feed on this species, with beetles, woodlice, slugs and snails being particularly effective dispersal agents. They are also transported, sometimes long distances, by the predators that feed on the organisms that feed on Stemonitis fusca. Lizards and salamanders are known to be dispersal vectors for Myxogastria spores, as are birds. I would think that woodpeckers, and gleaners such as brown creepers, nuthatches, wrens, warblers, and kinglets would be particularly important in spreading this myxo into a wide diversity of habitats.

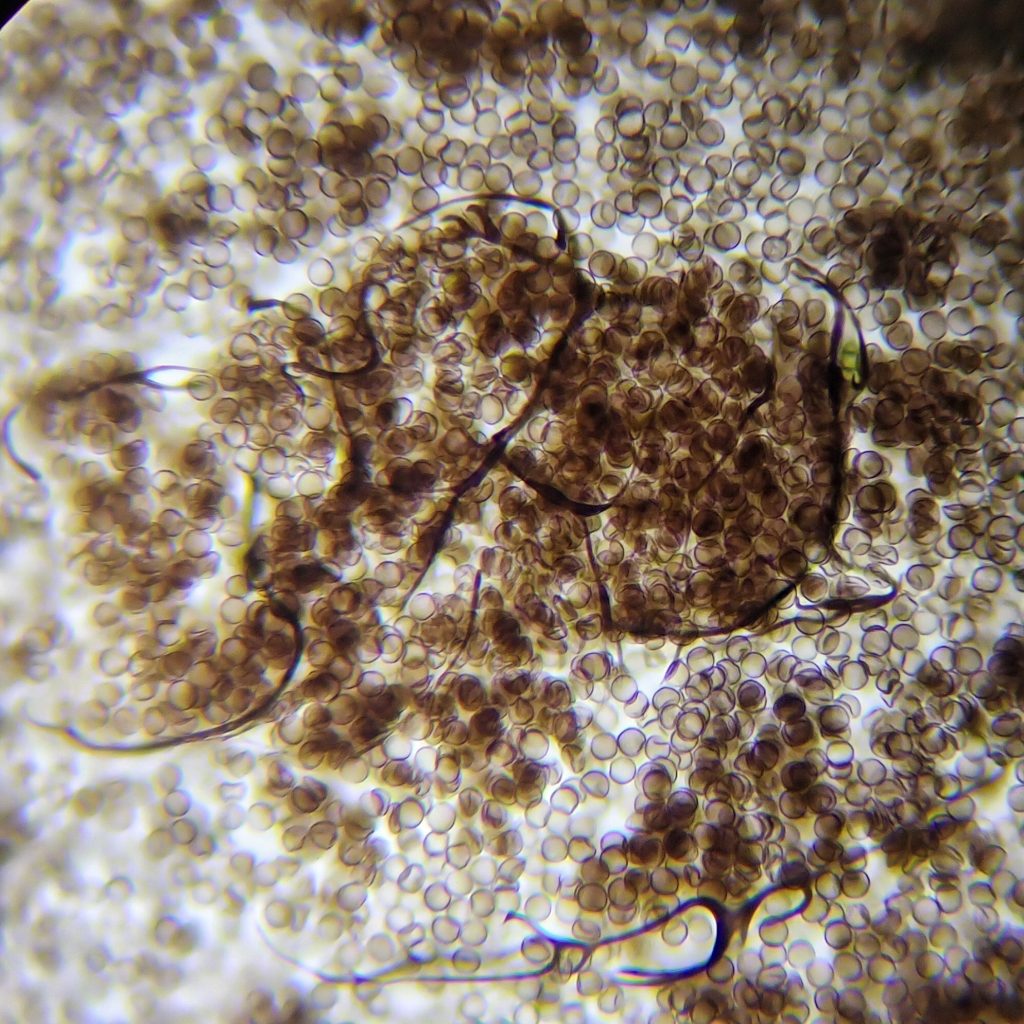

Much like their non-relative the fungi, the shape and colors of the sporangia of myxos are constantly changing, leaving only a fairly narrow window when they appear in their ‘classic’ form. See the website ‘Bizarre Creature of the Day’ for a very nice video of the process. For still shots of every stage from spore to sporangia see Dai/Okorley (2019). The problem is that, even in their classic form, very few myxos can be positively identified with the naked eye. But the good news is that, at any stage of sporulation, microscopic analysis can provide an answer, if you carefully follow a good key, such as this one.

Description-Relatively large (up to 20mm tall) chocolate brown to black cylindrical sporangia on a black stalk that is 1/4 to 1/2 of the total height; spores very dark in mass, warted to reticulate, 7.5-9μm in diameter; finely meshed surface net; in clusters of touching but not connected sporangia.

Similar species–Stemonitis axifera tends to be redder, with fairly smooth spores 5-7μm in diameter;S. nigrescens and S. trechispora have much shorter sporangia on much shorter stalks; S. splendens is often in larger clusters, with wide meshed surface net and fairly smooth spores; S. smithii has much smaller spores.

Habitat-Decaying wood or bark in forests and woodlands.

Range-Cosmopolitan; probably found region wide in appropriate habitats.

Eats-Bacteria, especially those feeding on decaying wood.

Eaten by-Parasitized by the fungi Nectriopsis candicans and Acrodontium myxomyceticola; Anisitoma sp. and Agathidium sp. and family Latridiidae beetles, as well as members of at least 6 other families of beetles; woodlice (including Oniscus asellus), some millipedes, a wide range of flies, various mites, nematode worms, and slugs and snails; sometimes grazed by mice.

Life cycle-According to one study (Dai/Okorley, et al; 2019) Stemonitis fusca can complete its entire life cycle, from spore to having mature spores, in 12 days; formation of sporangia is triggered by some combination of optimal growth being reached and the depletion of food resources, dark incubation time, the presence of niacin, and a substrate ph between 4.0-5.0.

Etymology of names–Stemonitis comes from the Greek words for ‘thread/stamen’ and inflammation/disease, but I cannot ascertain to what Gleditsch was referring. The specific epithet fusca is from the Latin for ‘dusky/brown/dark, and probably refers to the color of the maturing sporangia.

http://ncrfungi.uark.edu/species/20_stemonitisFusca/stemonitisFusca.html

https://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?search=Stemonitis+fusca

http://bizarrecreature.blogspot.com/2015/02/creature-139-stemonitis-fusca.html?m=1

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6973090/

https://www.myxotropic.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/MyxoKeys.pdf#page32