Let’s talk about slime molds! First off, let me admit that I knew almost nothing about slime molds before researching this, except for the fact that they are not molds, or a fungi of any sort. They are instead protists, a kind of catchall group for eukaryotes (having a nucleus within their cells) that are neither animals nor plants nor fungi. At present they are placed in the phylum Amoebozoa and the class Myxogastria. Traditionally they have been called the Myxomycetes, from the Greek words for slime and fungus, but since they are not, in fact, a fungus, there is movement towards calling them myxogastrids, which translates from the Greek as roughly ‘slime stomach’ and moves away from equating them with some type of fungus.

There are many reasons why that association with fungi was assumed in the first place, starting with the fact that they form fruiting bodies that are superficially mushroom like, and which then produce spores. But as soon as one looks deeper into their lifecycle that association breaks down. Because, just to start with, fungi do not go roaming around! Yep, slime molds move. And do so from birth, or in this case germination of their spore into 1-4 haploid protoplasts (unwalled cells), which can either be amoeboid or flagellate depending on whether there is enough moisture on the substrate to make a tail useful for locomotion. If conditions are not favorable these amoeboflagellate cells go into a reversible dormant phase by secreting a cell wall, thus inhabiting a microcyst, within which they remain viable for a year or more.

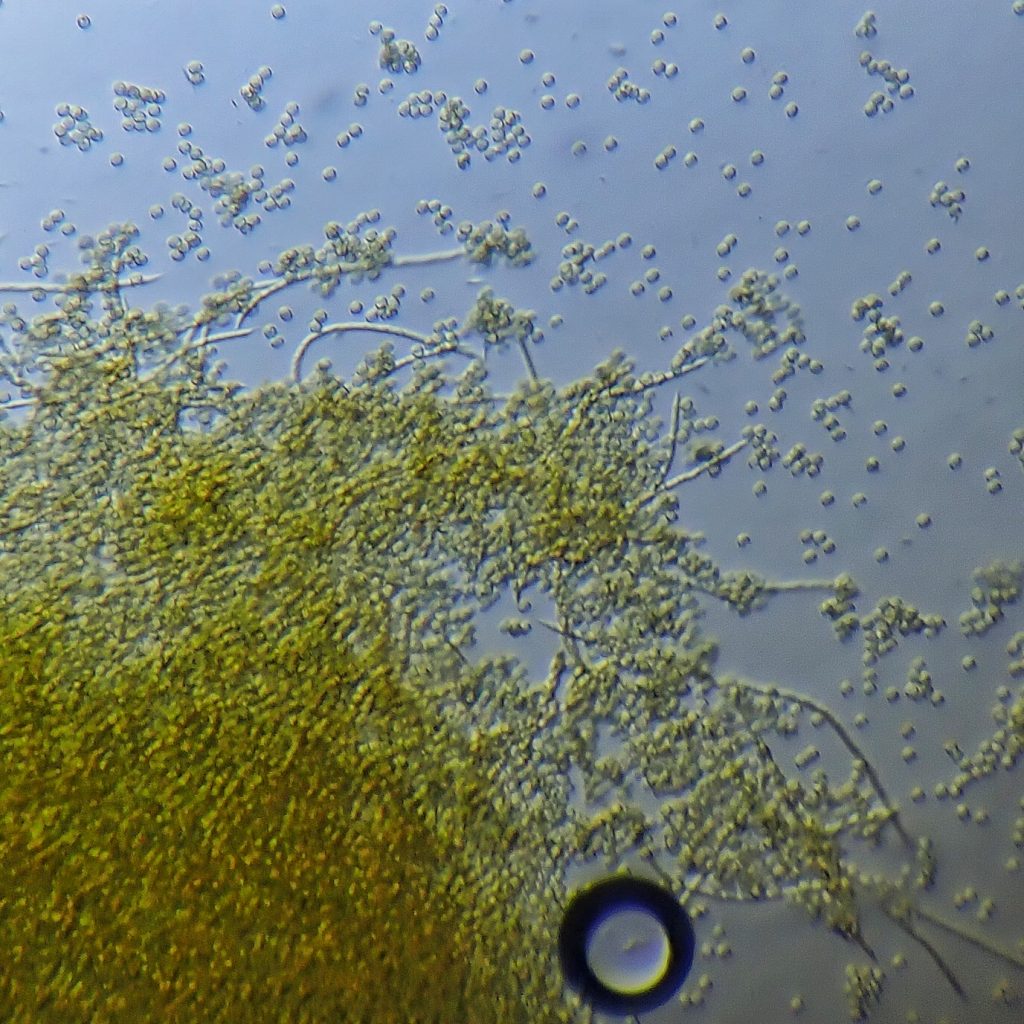

Eventually, if they are lucky, they encounter a compatible amoeboflagellate cell, and fuse both protoplasms and nuclei to become a diploid zygote. Once the zygote begins to grow by dividing its nucleus (and all divisions of the nuclei are synchronized within the cell) it is considered to be a plasmodium (a single cell with multiple nuclei), and myxogastrids are also called acellular slime molds because of this single celled aspect. During the ensuing period the plasmodium wanders around in search of food at a speed of about a millimeter an hour (though a few speedsters can hit 2 centimeters per minute). During cold, drought, and other unfavorable conditions the plasmodium can go dormant by forming macrocysts with hardened walls, and converting into a sclerotium, which will then reform into a plasmodium when conditions improve.

The plasmodium of myxogastrids is actually capable of things that seem to require some form of intelligence. For one thing they can keep track of time, since, after being subjected twice to a blast of cold air at the top of an hour, they will shrink back just before the next one is due. They can ‘remember’ the locations of food. And they can problem solve. Researchers have created mazes with oatmeal flakes marking preferred destinations and bright light to simulate known obstacles and Physarum polycephala myxogastrids have recreated the Tokyo railway system, the Interstate Highway system in the US, and the roads of the Roman Empire. One enthusiast even used them to figure out the best routes through his local IKEA, a nightmare maze if there ever was one. So how does a creature without a brain do this?

Partly it is because they do possess receptors that can sense chemical signatures for foodstuffs, and partly baecause they can send out multiple exploratory ‘feelers’ at one time. But as one study found, they also somehow utilize Transient receptor potential channels (TRP channels) to sense objects in space, and act on that information without any circuitry to convey it! There is apparently much we can learn about basal cognition from these creatures.

At some point the plasmodium transforms into something capable of producing fruiting bodies. The factors that trigger this may be lack of food, changes in moisture, temperature, or ph, solar cues, some combination of the above or something else entirely. But once sporulation has begun the entire plasmodium is transformed into sporangia, and the bulk of its protoplasm is turned into spores, which are released at maturity. And the cycle begins again.

This was my first myxogastrid identification, but it will not be my last! These fascinating lifeforms have been on the periphery of my radar for a couple of years, but having found one, and seen amazing photos of many more, I will be looking hard for them in the future. If this profile has piqued your interest in these unique creatures, I strongly suggest perusing the material in the many links at the bottom, because I have barely scratched the surface of the myxogastrids!

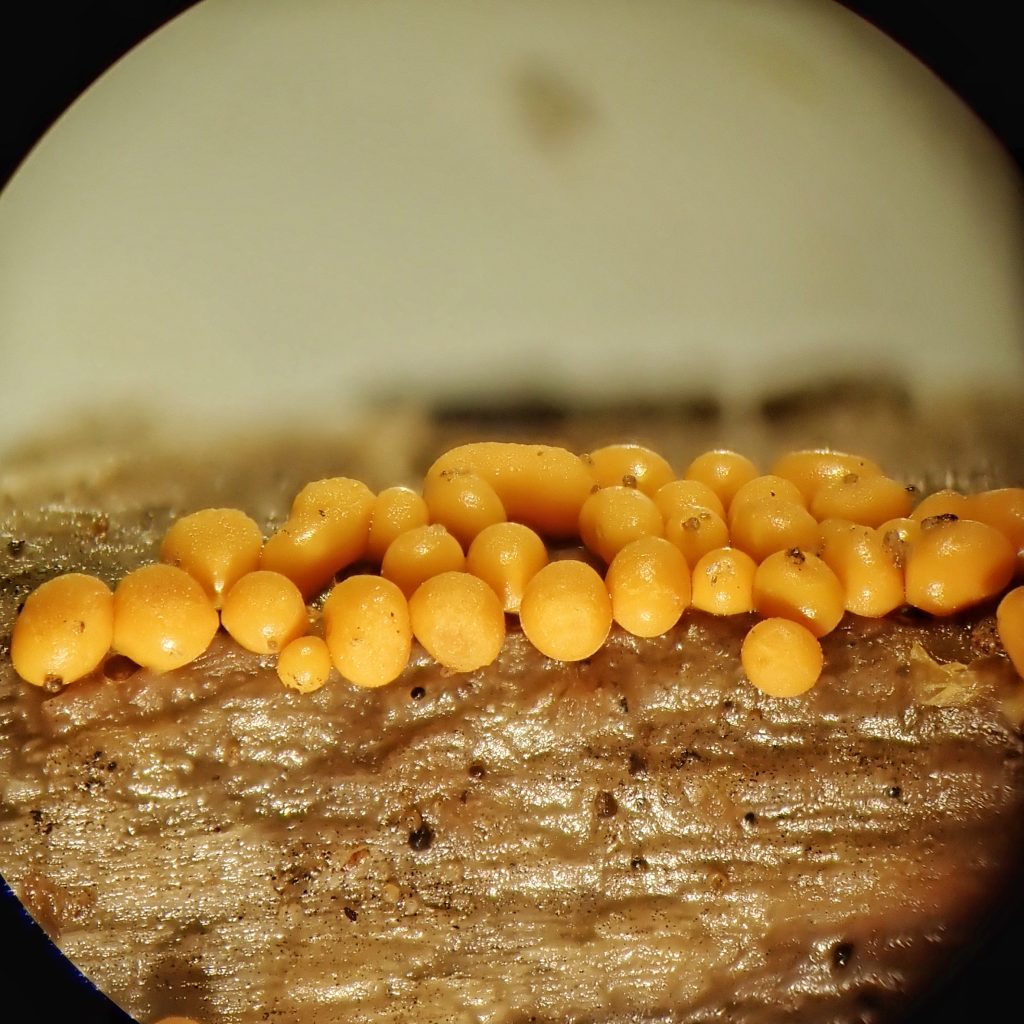

Description-Medium sized (for a slime mold- .5-1mm diameter) dull (when dry) yellow to greenish or brownish yellow sporangia; sporangia sessile (without a stalk), or on very short stalks; has 2-3 spiral bands on each elater; spores spherical, warted on the margin, 12-14 μm in diameter; the plasmodium is white, and as it forms into sporangia it remains white, before turning yellow brown as the peridium (covering over the spore mass) forms.

Similar species-Positive identification of most slime molds will require a good microscope and a key (such as this excellent one), and anything offered here is just as a starting point for in-the-field identification; Trichia favoginea is bright, shiny and even iridescent, yellow; T. lutescens sporangia smaller (.1-.5mm diameter); other sessile Trichia much darker in color; other brownish yellow Trichia have noticeably stalked sporangia; Oligonema spp. Tend to have sporangia densely crowded or heaped.

Habitat-Decaying wood, and rarely on bark.

Range-Worldwide; probably found region wide except for shrub steppe and other open, arid habitats.

Eats-Primarily bacteria, but may also consume various spores, yeasts, and algal cells, and probably extracts some nutrition from its substrate.

Eaten by– Round fungus beetles (family Leiodidae) in the genus Agathidium, and many woodlice, including Oniscus asellus, feed on this species; other known consumers of myxogastrids are Collembola (I’m guessing the little globular springtails in my photographs weren’t there for the view), some millipedes, a wide range of beetles and flies, various mites, nematode worms, and slugs and snails; most of these predators also probably do somewhat pay back the myxogastrids by functioning as spore dispersers.

Reproductive timing– Tends to form sporangia in the fall.

Etymology of names– Trichia is from the Greek word for ‘hair’, and probably refers to the hair-like elaters surrounding the capillitium. The specific epithet varia is from the Latin for ‘different’, and may refer to the varying forms of this species.

http://www.hiddenforest.co.nz/slime/family/trichiaceae/trich10.htm

http://museumofdust.blogspot.com/2006/05/garden-slime-molds.html?m=1

https://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?search=Trichia+varia

Can Slime Molds Think? | Harvard Magazine

https://abneyfungi.wordpress.com/2012/10/19/trichia-varia-a-slime-mold-2/amp/

Slime Molds (U.S. National Park Service)

http://plantclinic.cornell.edu/factsheets/slimemolds.pdf

https://www.projectnoah.org/spottings/9354089

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15572536.2003.11833169?needAccess=true

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plasmodium_(life_cycle)

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transient_receptor_potential_channel

very interesting – thoroughly enjoyed your contribution, many thanks

Thank you, Theresa!

Glorious

Thanks Ray! Do you remember what species your pets were back in college?

Hi Dan

I work to combine PNW ecology with adventure in my books. I recently published “The Slime Mold Murder,” which has illustrations of regional slime molds by Olympia artist Duncan Sheffels. You might enjoy it.

Thanks so much for your informative posts!

Thank you Ellen! I read your novel Evoangel. It was good! Entertaining and informative both. I’ll look into ‘The Slime Mold Murders’.