Last Friday I did my weekly walk with my nbo Morgan and my granddog Junior. Afterwards, as we were driving back down the Kalama River to where they had left their car, Morg discovered ticks crawling on Jr. I was able to capture 2 of them, and Morg found 4 more in Jr’s ensuing bath and comb out, but Morgan and I managed to avoid any on ourselves. This was a good reminder, both of the fact that Jr’s bug repellents were wearing off, and that ticks may be encountered at any time of the year, not just during what I think of as ‘tick season’ in the spring.

Ixodes pacificus, the Western Black-legged Tick, are the most dangerous of our PNW ticks. They are the primary vector (transmitting something from an infected animal to a non-infected one) for the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) in our region. The good news is that studies have shown that less than 2% of Western Black-legged Ticks are carrying the bacteria (1.48% of 1687 tested in this study). The bad news is that Ixodes pacificus is also a vector for Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which causes anaplasmosis, and Borrelia miyamotoi, which causes a form of relapsing fever, as well as a few other nasty little pathogens.

None of this is said to promote fear of ticks, but it would be foolish to ignore the very real dangers they present. Heavily spraying clothes and footwear with DEET or picaridin containing repellents has proven to be effective at preventing attachment, especially in conjunction with wearing light colored clothing so that hitchhiking ticks may be spotted before they reach the skin. Post hike tick checks are also a very good idea. It usually takes awhile (up to a few hours) for ticks to attach, and supposedly it takes a few more hours (possibly as many as 24) before the pathogens are transmitted to the host.

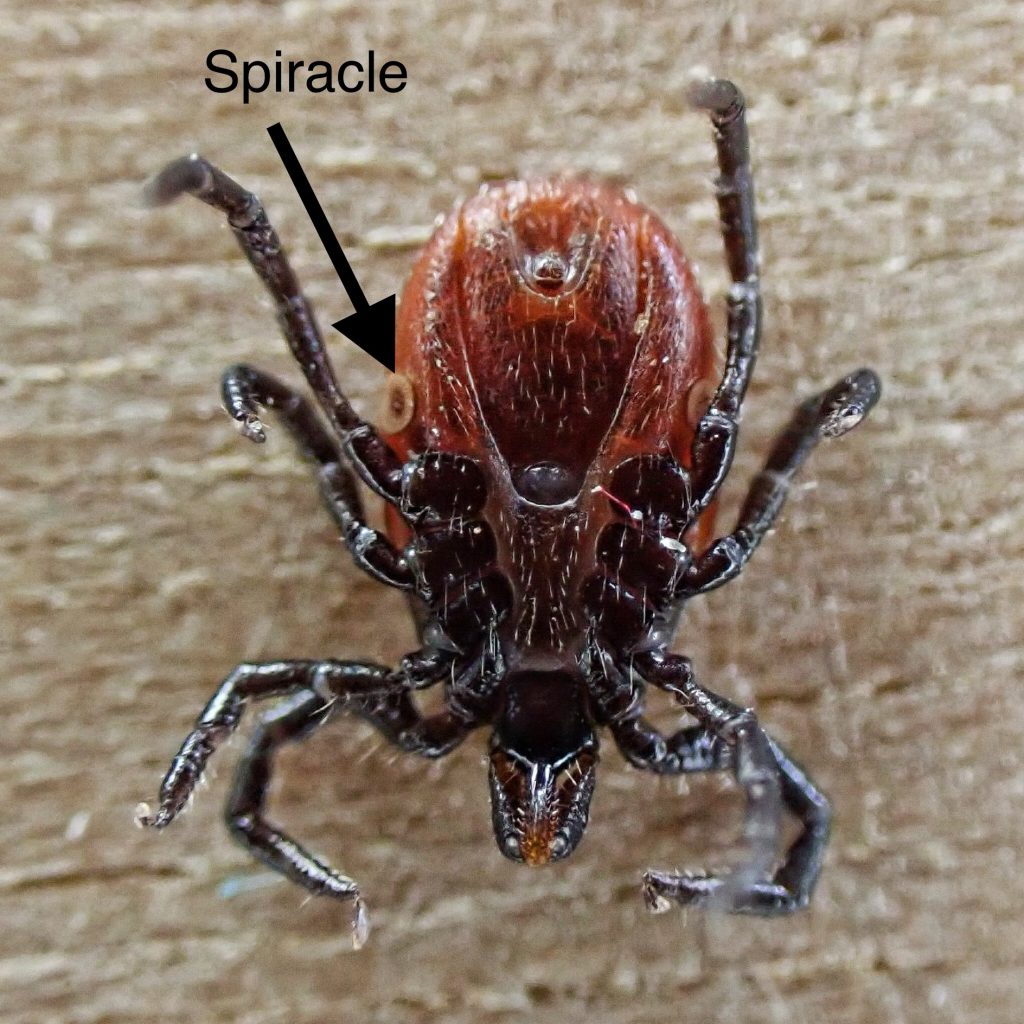

Ticks found crawling on you or a pet should be crushed or put in alcohol (flushing them down a toilet is not a guaranteed way to kill them, because they can close their spiracles and avoid drowning for extended periods). Those found attached should be removed by grasping its head (try not to squeeze the body because that may flood the wound with infected blood) with tweezers and pulling with a twisting motion (and these should always be saved in alcohol so that they can be tested if symptoms occur), and the wound should be cleaned and disinfected. These simple procedures will significantly reduce the risk of contracting a tick borne illness. In 40+ years of tromping through the PNW I have only had 4 ticks attach to me (although I’ve found a few dozen on my clothes and skin), and in none of those cases was I following proper tick repellent protocols.

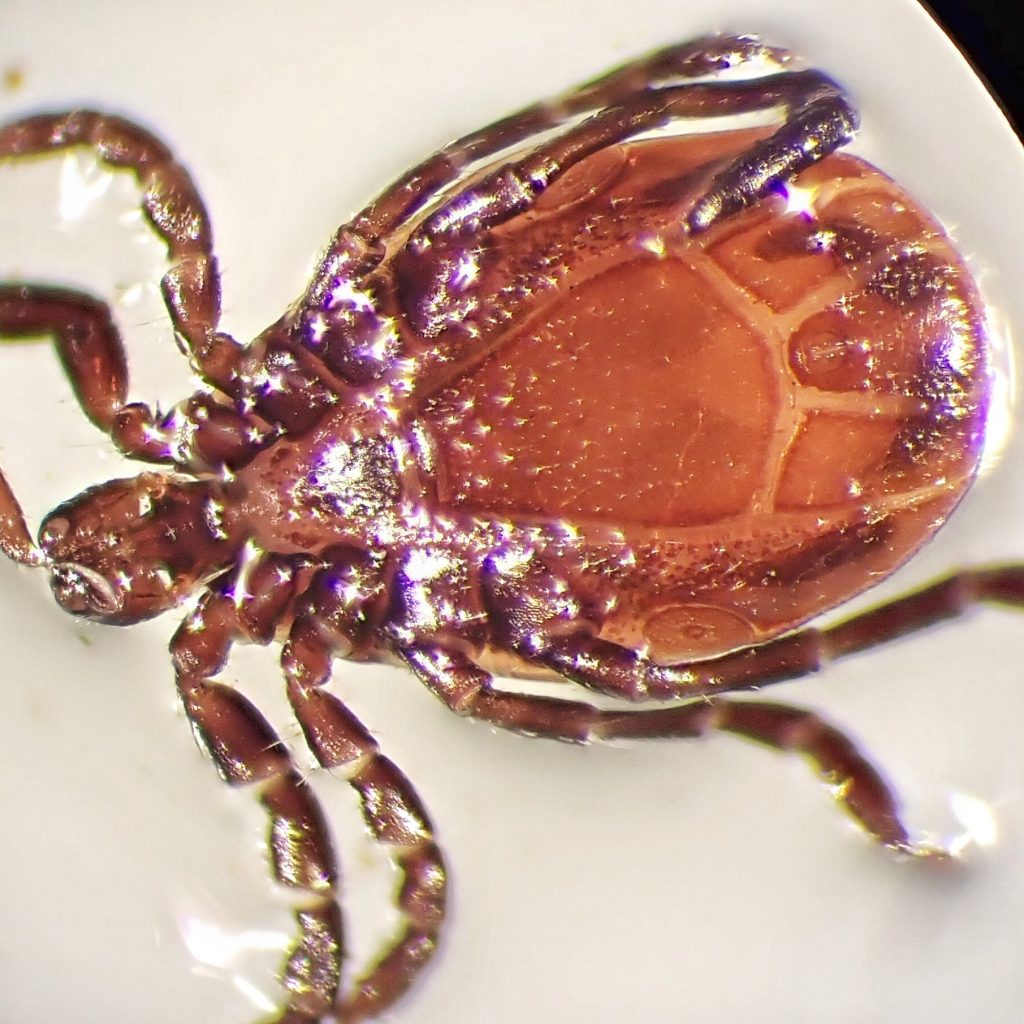

So, enough gloom and doom. Because these arachnids are actually very cool, at least from a creepy bug with a bizarre lifecycle perspective. Adult Ixodes pacificus become active in late fall or early winter. It is believed that breeding begins then. Once inseminated, the females (which can be differentiated from the males by having a circular scutum [also called dorsal shield; think carapace or pronotum] that does not extend over the abdomen) begin to seek a host (usually a deer, but they also utilize coyotes, bobcats, ground squirrels and many other mammals, including of course, humans, dogs, cats, and livestock). They do this by perching on grasses, and branches and leaf tips, front legs outstretched to clasp anything that brushes their perch.

If they are successful at finding a host, then after they are replete (which takes about 10-12 days wherein they consume 50-75 times their body weight in blood) they either enter diapause and delay ovipositing (if it is still winter conditions and unfavorable for the eggs to survive) or begin ovipositing into the soil and leaf litter. Females may lay 800-1300 eggs in the next month. Those eggs hatch in 7-8 weeks, usually from mid July through August. It appears that the females die shortly after ovipositing, and adult males may die after breeding.

The larval hatchlings (which only have 6 legs, rather than the 8 of nymphs and adults) go into a period of quiescence, and do not seek a blood meal until the following late winter/early spring. After they are replete they drop from their host, and moult into nymphs in mid summer. The nymphs also are quiescent after the moult, and don’t seek a host until the following late winter. Unlike the adults, larval and nymphal ticks most commonly search for a host from within leaf litter, or on moss logs and rocks. This is because the larvae and nymphs are most active during the drier months, and need the humidity inherent to the forest floor. Adults are active during wetter times and don’t need as much shelter to prevent desiccation.

At these early stages their preferred hosts are primarily mice, ground foraging birds, and lizards, and the blood ofSceloporus occidentalis (Western Fence Lizards) contains a protein which kills off the bacteria responsible for Lyme disease. This is one of the primary reasons Ixodes pacificus has a much lower infection rate than Ixodes scapularis (known as the Deer Tick or Eastern Black-legged Tick, and only found east of the 100th meridian, said to be ‘where the Great Plains begin’)(any Tragically Hip fans out there?) which has infection rates from 15-30%. Nymphs moult and become adults in mid summer, but those adults are quiescent until late fall, when the whole cycle begins again.

And, just as a final set of visuals, here is the process by which a Western Black-legged Tick attaches to its host. Ixodes pacificus are eyeless, but on the tarsi of their front legs they have heat and CO2 sensors (Haller’s organs) that can detect these qualities from yards away. Once activated the tick begins clawing the air with those front legs, and, if it is lucky, they contact and clasp some part of a potential host. Then it crawls around, searching for a secluded spot where it won’t be disturbed, preferably one with some cover, like an armpit, the hairline on the back of the neck, or other hirsute areas (although I have had one attached near my hip, and one at the base of the shoulder blade on my back). Then it inserts its barbed feeding tube (hypostome), which also acts as an anchor, and for good measure cements it it place, all the while secreting an anticoagulant saliva to keep the blood flowing. And an anesthetic so the host doesn’t feel the full extent of the invasion. Kind of a thoughtful touch, that, though its purpose is to help the tick avoid detection. They only take a few drops, really. Less than I’d lose with a shaving nick. If it wasn’t for the whole transmission-of-a-horrible-disease thing, I’d be willing to share. It would be like having a pet vampire. I (thanks go to Craig Sondergaard for this idea) could hang them on my earlobes like jewelry…

Description-Small (adults are 2.5-3.5mm long and 1.5-2.5mm wide) tick with black legs; females have a circular black scutum and red abdomen, and males have an elongated black scutum, with a red abdominal margin; inner spur on 1st coxa much longer than the outer one, and it extends past the edge of the 2nd coxa.

Similar species–I. spinipalpis has scutum longer than wide in females; I. angustus with spurs on 1st coxa the same size; Dermacentor sp. usually brown, with a light colored scutum.

Habitat-Brushy open areas near moist to mesic forests and woodlands.

Range-West Coast of North America; in our region they are found from the Cacades west, in the Columbia River Gorge, and in sw Oregon/nw California.

Eats-Blood; hosts are primarily lizards, small mammals, and ground feeding birds as larvae and nymphs, and larger mammals as adults.

Eaten by-Insectivores (although they are arachnids) of all classes.

Adults active-Late fall through late spring.

Life cycle-Larvae to nymph to adult; one stage per year, thus 2+ years for a lifespan.

Etymology of names–Ixodes is from the Greek words for ‘like birdlime’, which is an adhesive agent used to trap birds. I have no idea what the reference is. The specific epithet pacificus has to do with this being a strictly western species.

https://bugguide.net/node/view/43665

https://academic.oup.com/jme/article/38/5/684/908383

https://www.tickcheck.com/info/tick-identification

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/surveillance/WesternBlackleggedTick.html

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/resources/TickSurveillance_Ipacificus-P.pdf

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3898886/

https://www.ticklab.org/western-blacklegged-tick

https://academic.oup.com/jme/article/53/2/250/2459687

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anaplasma_phagocytophilum

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relapsing_fever

Here in the east we have our own blacklegged tick (usually called the deer tick) which evidently is much more effective in transmitting Lyme Disease. After working in the woods, I have found as many as 25 on my clothes and wandering around on my person. A colleague gave me a tip about treating field clothes with permethrin, which affords several weeks of protection. It works! Another strategy to reduce tick populations relies on the fact that their hosts are mostly mice (not deer). PVC tube stuffed with permethrin treated cotton are scattered about the area. The mice collect the cotton for their nests, and both the mice and the nests pick up the permethrin, which kills any ticks that come in contact with it. Another story often heard is that opossums eat loads of ticks. They do, but only those that get on them; they don’t seek out ticks as food.

Thanks for that information, Bill! I did the permethrin thing a couple years ago, and it worked very well. Until I finally had to wash the clothes. I’m going to do that again this spring. Very interesting about permethrin treated cotton. I didn’t know it would also kill them.

Wow! Very interesting, but spooky, information, Dan! I lived on the west side of the state for over 45 years. For 20 of those years I was a habitat specialist and fish biologist with the State of Washington. I was out in the woods, farm lands and along many streams as part of my job. I never saw a tick until I moved to Spokane in 1993. I also worked here as a fish habitat specialist until 2006. During that time I did a lot of hiking in tick-infested land along many streams in Eastern Washington and Idaho. During these forays into the brush most of my comrades, at the end of the day, would find 2-3 ticks beginning to attach but I have seen only ONE tick trying to attach to me since I have lived here! It must be my body scent or maybe ticks don’t like fish biologists!

Thanks Mark! Are you by chance a big fan of garlic? A lot of old timers swear by its efficacy as a tick repellent. Which is another good reason to eat a lot of garlic, not that I needed one. My wife has the opposite problem. When we first got together, and I was tick ignorant, she often found several on her, and I wouldn’t have 1. And they would often attach to her in minutes!