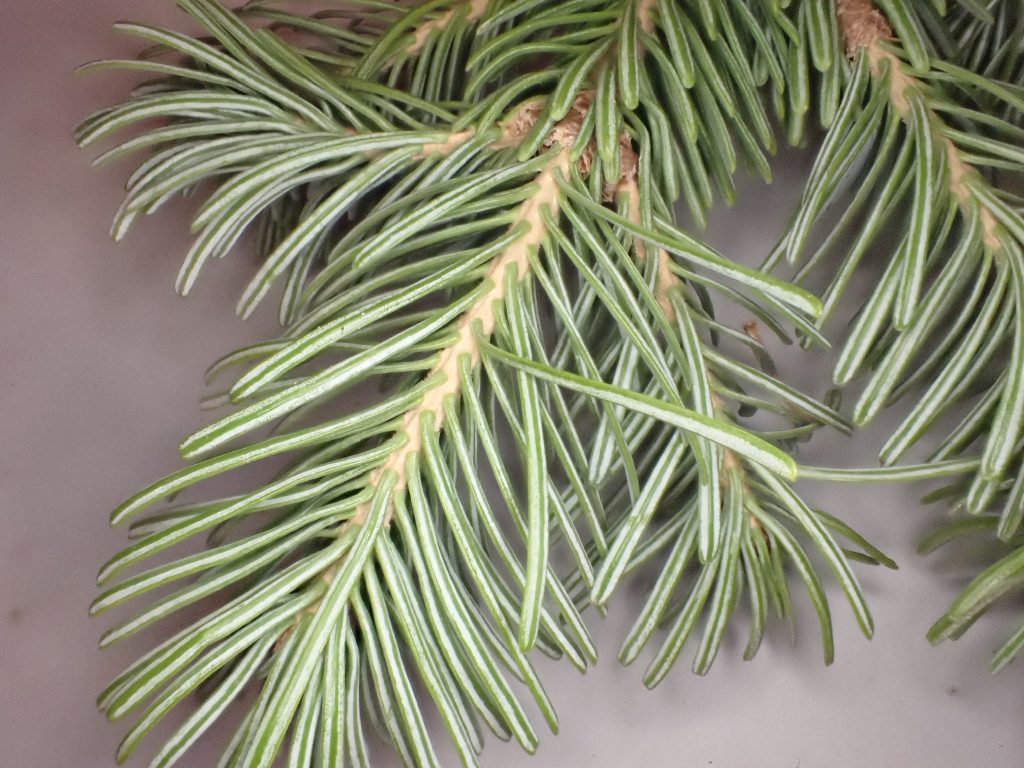

Now we turn our attention to Abies lasiocarpa (subalpine fir, which used to be called alpine fir, until someone pointed out that alpine means the region above timberline) the other common true fir in our region that has stomatal bloom on both sides of the needles. It is not difficult to examine the needles of subalpine fir, because they almost always have branches that grow all the way to the ground. And though the needles of both Abies lasiocarpa and A. procera are 20-40mm long, are massed on the top of the twig, and tend toward blue green in color, those of subalpine fir have only a single wide band of stomatal bloom spreading across a trough on the dorsal surface, as well as a pair of lines of stomatal bloom on the underside, while noble fir have two lines of stomatal bloom on top and bottom of the needle (separated by a groove on the top side and by a ridge underneath). This difference is easily noted with the naked eye.

These two species are also readily segregated on the basis of their cones, with those of Abies lasiocarpa being purple to indigo blue, with bracts that are shorter than the scales, and are 2.5-4” long, whilst those of A. procera are straw to olive colored because of exserted bracts that cover most of the scales and are reflexed (giving them a spiky or shaggy look), and are 4-6” long. Even from a distance one can often identify subalpine fir, because of their very narrow profile and the aforementioned branches going all the way to the ground (though Engelmann spruce also have a narrow profile it is seldom as narrow and is more bullet shaped, as opposed to the acute isosceles triangle of subalpine fir) whereas mature noble fir often have a clean bole for 1/2-2/3 of their length.

Because of their thin bark, subalpine fir are not resistant to fire, and their low hanging branches usually carry even moderate fires into the crown. Due to their shallow roots, they are also prone to being knocked down in high winds (technically this is called windthrow), although root configuration usually has much to do with the rocky, mineral soils in which they can grow. This species often establishes in areas where few other trees could grow, such as exposed ridges, lava beds, and avalanche corridors, although it establishes best in moist humus in moderate shade. This is a slow growing species, but it may produce seed after it is twenty years old, and though trees around 500 years old have been found, those over 250 are rare. For a more complete account of the ecology and silviculture of Abies lasiocarpa, I suggest visiting Alexander/Shearer/Shepperd’s treatment at Abies lasiocarpa (Hook

Because it often grows in inaccessible areas, subalpine fir is not often targeted for commercial harvest. But as a byproduct of clearcutting other timber it is sometimes used for dimensional lumber, although most often it goes into pulp. Indigenous peoples had many uses for this tree, including eating the inner bark and seeds, chewing hardened pitch as gum, and grinding cone fragments into powder, mixing it with fat and marrow, and eating it as a confection at social gatherings (it was said to also help digestion). The boughs and branches were used to floor sweat lodges, as a base for bedding, and to walk on after swimming to keep the feet clean. The wood was used for furniture, and for insect resistant boxes in which to store ceremonial clothing. They also used it for a variety of medicinal purposes, including using bark, needles, and pitch in various forms to treat stomach ailments, bruising, tuberculosis, colds, and flu, and inhaling the smoke for headaches. For a more complete list see the 105 entries on the Native American Ethnobotany Database.

Description– Large (though small for a fir; usually no more than 100’ tall and 3’ in diameter, though specimens up to 150’ tall and 6’ dbh have been found) conifer with a narrow profile, purple to blue cones, needles with stomata on both sides, and ash grey bark; upper surface of needles with a single, solid band of stomata; bark generally smooth, but has resin blisters, and becomes thinly furrowed with age.

Similar species-See above for Abies procera; A. grandis and A. amabilis only have stomatal bloom on the underside of the needles; Douglas-fir, western hemlock, and mountain hemlock have pendent cones, and leaf scars that are at least a roughening of the bark; Engelmann spruce have persistent, peg-like leaf bases, pendent cones, and stiff, pointed needles.

Habitat– Montane conifer forests from 3,000’ elevation to subalpine.

Range-Western North America; found in all of the mountains of our region, except seemingly absent from even the higher elevations in the Coast Range.

Reproductive timing-Cones are pollinated and fertilized in late spring/early summer, seeds are mature in September, and are disseminated from October into December.

Eaten by-Many of the organisms that consume parts of these trees are the same as for other firs, and it’s the same for vertebrates, with grouse, deer, and elk browsing the foliage, and many birds, squirrels, and chipmunks eating the seeds; as with many true firs, the aphid-like, introduced true bug Adelges piceae is a serious pest, and causes significant mortality; the bark beetles Pseudohylesinus sericeus, Scolytus ventralis, and Dryocoetes confusus consume the phloem; larvae of the leaf mining moths Archips packardiana, and those in the genera Choristoneura and Coleotechnites, as well as the moths Syndemis afflictana Caripeta divisata, Cladara limitaria, Ectropis crepuscularia, Enypia griseata, E. packardata, E. venata, Epirrita autumnata, E. pulchraria, Eulithis propulsata, Eupithecia spp., Feralia jocosa, Gabriola dyari, Hydriomena californiata, H. irata, Lambdina fiscellaria, Melanolophia imitata, Neoalcis californiaria, Nepytia phantasmaria, Operophtera bruceata, Pero behrensaria, P. morrisonaria, Sicya macularia, Tetracis pallulata, Thallophaga hyperborea, Trichodezia albovittata, Dasychira grisefacta, Orygia antiqua, O. pseudotsugata, Aseptis binotata, Cosmia praeacuta, Lithophane innominata, Panthea virginarius, Syngrapha celsa, S. alias, Xestia mustelina, Dasypyga alternosquamella, and Dioryctria abietivorella; ambrosia beetles in the genera Gnathotricus, Platypus, Trypodendron, and Xyleborus, and the longhorn beetles Semanotus litigiosus, Rhagium inquisitor, Phymatodes maculicollis and Monochamus scutellatus, as well as the horntail wasps in Sirex, including Sirex varipes, attack weakened or dying trees.

Etymology of names– Abies is from the Latin word for firs. The specific epithet lasiocarpa is from the Greek words for ‘wooly fruit’, but according to Professor of Dendrology Dale Bever, it is the young twigs that are actually hairy.

Abies lasiocarpa (subalpine fir) description

Subalpine Fir, Abies lasiocarpa | Native Plants PNW

BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

Burke Herbarium Image Collection