I’m going to take a short break from talking about the organisms I found on my trip to sw Oregon/nw California. In this profile I want to talk about the Western larch (Larix occidentalis), a conifer that I’d never seen up close until my desire to learn about the conifers sent me in search of them. I’d seen them on distant ridges in the fall, their bright gold needles (which signaled to indigenous people that pregnant bears would be denning soon) and conical shape unmistakable even from a great distance. Well, unmistakable after the first time that I commented on ‘those sickly looking trees over there’ and was informed as to what they were.

I can still picture a long ridge that was apparently almost all western larch, on a dark and bitter November afternoon outside Kalispell, Montana, and those trees seemed to glow, so stark was the contrast between them and the rest of the world. We were re-siding a house at the time, and every time I had to go to where the saw and siding were I would detour around the back of the house so I could soak in some of that glorious color.

Larix sp. in general are deciduous, and Larix occidentalis, and it’s alpine cousin L. lyallii are the only extant deciduous conifers native to the PNW. It appears that the primary benefit to larches of being winter deciduous is conservation of water, and not having to feed those needles during the low light periods of winter (Gower/Richards; 1990). The bald cypress that are native to the se US are also deciduous, and are sometimes planted as ornamentals in our region. The deciduous dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) has apparently been extinct for 20 million years in North America (there are fossils in the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument), but can still be found growing wild in China, and has become a popular ornamental. There is an interesting article on this species by Max Paschall (2020) that can be found here.

Western larch is extremely intolerant of shade, and only as seedlings can it handle even moderate shading. To make up for this it is a very fast growing tree that can stay ahead of same age trees of different species in a race for the light. Because of their thick bark, low flammability foliage, and elevated and open branching, mature western larch are quite tolerant of fire, and in fact, because of their shade intolerance, require it to maintain their place in mixed Doug-fir/grand fir forests. Due to its substantial root system Larix occidentalis doesn’t suffer much from windthrow, but trees isolated by fire or logging are vulnerable. Because they are deciduous they don’t usually accumulate a heavy load of snow and ice, so they don’t lose many branches during winter storms. Being deciduous they also don’t accumulate as many pollutants (such as fluorine and sulfur dioxide) as other conifers, although young trees are susceptible to the toxicity of those chemicals. Under good conditions these trees may live over 800 years. For a more complete picture of their ecology see Schmidt/Shearer.

This is the largest of the North American Larix species (which includes the tamaracks; another common name for this tree is western tamarack), and produces one of the most valuable timbers in the western United States, being used for lumber, fine veneer, poles, ties, mine timbers, and pulpwood. So valuable, in fact, that there are two Larch Mtns near the Columbia River, one in Oregon and one in Washington. But there are actually few if any larch there, and the names came about because the abundant true firs were thought to contain inferior quality wood (more or less accurate for all firs except nobles) so they were duplicitously marketed as larch. This would have been a good thing to know before I spent a disappointing day traipsing about Oregon’s Larch Mtn. in search of western larch, since that lack was the only disappointing aspect of that day. The pitch is also commercially valuable, since it is similar to gum arabic, and is used as an emulsifier or stabilizer in foods and medicine.

Indigenous peoples didn’t have many food uses for this tree, and beyond sometimes eating the cambium in springtime, they all revolved around the pitch as gum, candy, or syrup. But there were many medicinal uses for this tree. The pitch was often mixed with tallow and applied as a poultice to cuts and sores, and could be chewed by itself for sore throats. Infusions of the bark were used to treat tuberculosis, flu, and colds and coughs, as well as as a wash for wounds. A decoction of bark and small branches could be used to stimulate the appetite, treat an ulcer, and as birth control after childbirth. A decoction of the plant tops was used to treat cancer, soak arthritic limbs, as a blood tonic, and as an antiseptic wash for cuts and sores. The wood was used for the center pole of the Sundance, and in the making of bows. Rotten wood was used to smoke buckskins, and pitch was burned to make a reddish face paint. For a more complete account of their use by indigenous people see the 45 entries on the Native American Ethnobotany Database.

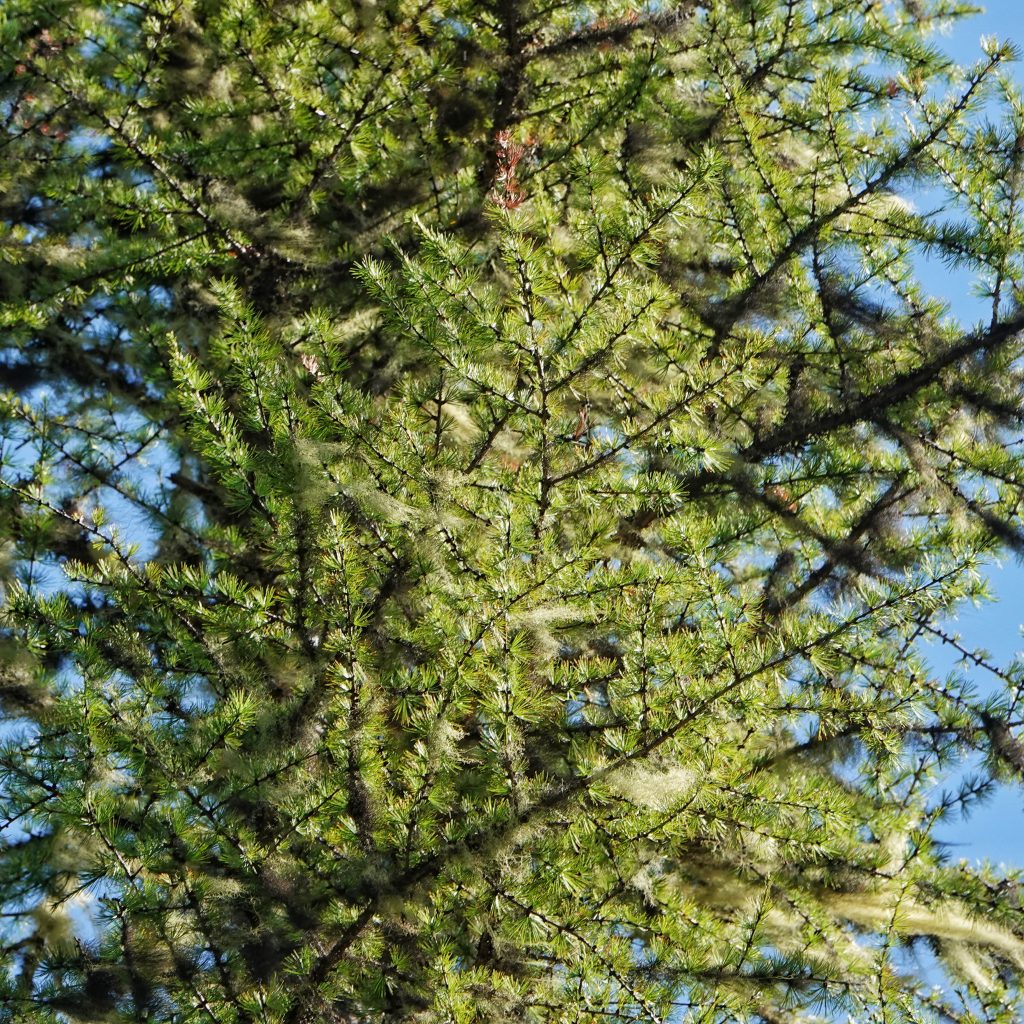

Description– Medium sized (up to 130’ tall), straight trunked trees with few lower limbs, a narrow, well spaced, conic crown, and needles in spiral bundles of 15-30 needles; needles deciduous, bright green in spring, emerald green in summer, yellow green to gold in the fall, 3/4-1 3/4” long by .5-1mm wide, triangular in cross section; trunks to 6’ dbh, bark reddish brown, scaly, and deeply furrowed with age; twigs are stout, with prominent pegs where needles have fallen off; pollen cones less than 10mm, seed cones 1-1.5” long, with exserted bracts tipped with awns.

Similar species– Larix lyallii has square needles, and usually has more than 30 per bundle; no other native conifer has 15 or more needles in spiral bundles.

Habitat– Mesic to arid mixed conifer forests from 1,000’-6,000’ elevation.

Range-Native only in the PNW; grows wild in the Cascades primarily on the eastern slopes, as far south as the South Sister area, though there are also populations in the middle Columbia River Gorge and nearby montane locations; also found in nw Montana, n Idaho, ne Washington, and in the Blues and Wallows; there is a disjunct population along Clover Creek road, south of Lake of the Woods in Klamath County, Oregon; isolated trees that are either nursery stock or descendants of nursery stock may be found in the Willamette Valley.

Reproductive timing– Pollen and seed conelets appear from mid-April to mid-May, usually before the vegetative buds open; pollination happens between late May and mid-June; cones mature in August, and begin to open in September; cones open when the moisture content drops to 35-40%, and most seed is dispersed by the end of October; cones usually fall during the winter, but may remain attached until the following summer.

Eaten by– Larval host for the moths Argyrotaenia dorsalana, Henricus fuscodorsanus, Macaria sexmaculata, Spodolepis substriataria, Eupithecia misturata, Dasychira grisefacta, Lithophane thaxteri, Feralia jocosa, Lambdina fiscellaria, Zeiraphera improbana, Nepytia canosaria, and the leaf mining moths Coleophora laricella, Archips packardiana, and Choristoneura occidentalis, as well as the Pine White butterfly; the bark beetles Dendroctonus pseudotsugae, Ips plastographus, and Scolytus laricis; larvae of the sawflies Pristiphora erichsonii, Anoplonyx occidens, and A. laricivorus; grouse eat the buds; Pine Siskins, crossbills, redpolls, and many other birds eat the seeds; squirrels, chipmunks, porcupines, and other rodents eat seed, seedlings, and bark; bears strip the bark to feed on the sapwood; dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium laricis) is a common parasite of larch; also attacked by the needlecast fungus Hypodermella laricis, the quinine fungus Fomitopsis officinalis, and the conk Porodaedalea pini; the longhorn beetles Pogonocherus pictus, Pygoleptura nigrella, Rhagium inquisitor, Tetropium velutinum, and Xestoleptura tibialis utilize dying and dead trees as larval hosts.

Etymology of names– Larix is the Latin word for a larch tree. The specific epithet occidentalis is from the Latin word for western, a fitting name since it only grows west of the Rockies.

OregonFlora Larix occidentalis

BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

http://nativeplantspnw.com/western-larch-larix-occidentalis/

Larix occidentalis (western larch) description – The Gymnosperm Database

https://www.oregon.gov/odf/Documents/forestbenefits/WesternLarch.pdf

Sci-Hub | Larches: Deciduous Conifers in an Evergreen World | 10.2307/1311484

https://www.shelterwoodforestfarm.com/blog/2020/7/7/metasequoia-creating-a-forest-of-living-gods

In the spring, the new needles are just about the softest thing you’ll find anywhere in nature. These are highly huggable trees.

Cool! I’ll try to take note of that next spring.