There is something almost homey about thimbleberries (Rubus parviflorus), with their large, soft leaves, lack of thorns, and large, graceful, tissue-thin white flowers. They are somehow comforting to look at. Either they don’t produce very many fruits, or they get eaten immediately by wildlife, because I seldom find the composite drupes that they produce. When I have found and eaten them they are pleasant, but not great, and rather seedy yet insubstantial.

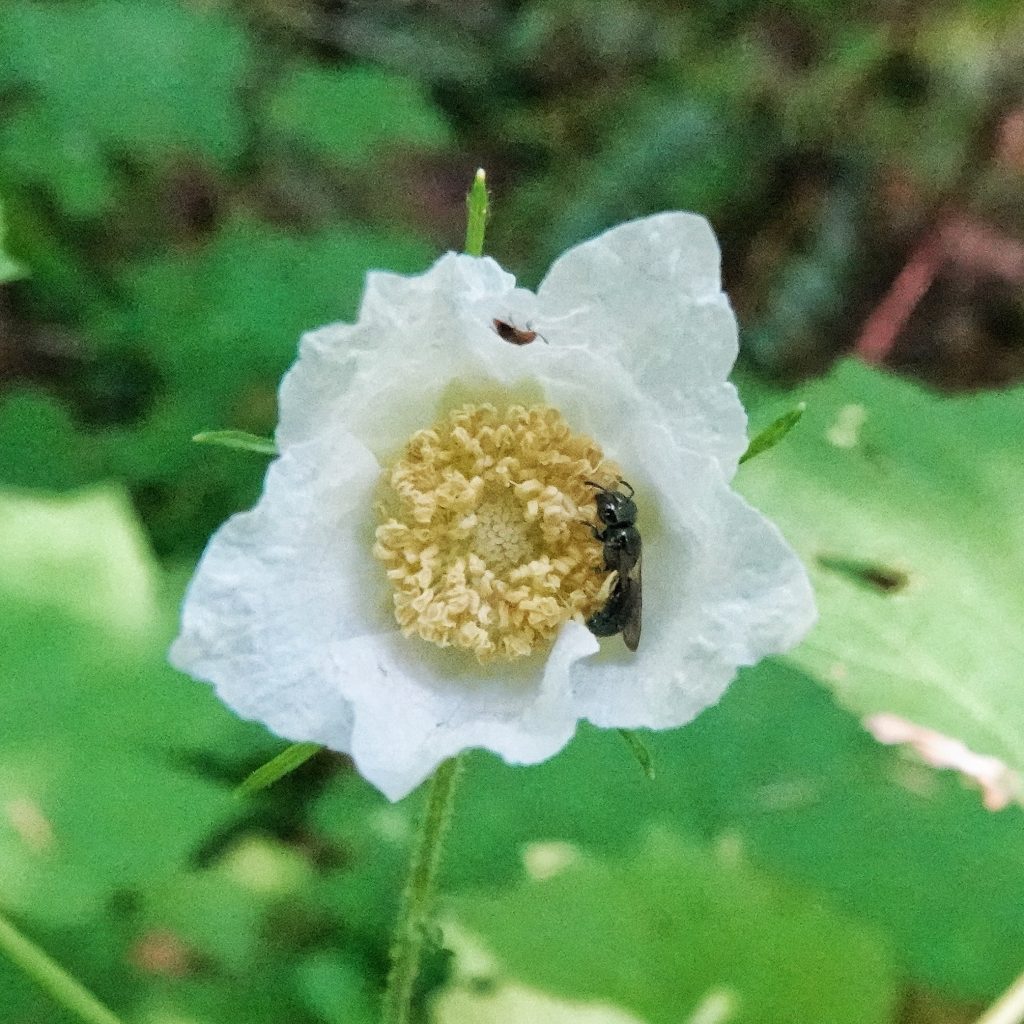

My favorite thing about this plant is that it attracts a fair number of insects to the blooms, and they are often quite sedentary when ensconced in the flowers, allowing for good, closeup photo opportunities. Since it can handle anything from full sun to full shade (although it apparently prefers partial shade), and in addition to its attractive foliage and delicate, elegant flowers is a beneficial plant to a variety of wildlife, it is becoming popular with gardeners trying to introduce more native plants into their gardens.

Ethnobotany– “Natives ate the young shoots, raw in early spring. The berries were eaten fresh, mixed with other berries. Some tribes collected unripe berries and stored them in baskets or cedar-bark bags until ripe; others dried them like salal berries, although some considered them too soft for drying. The large leaves made handy containers for collecting berries and were also used for wrapping and storing elderberries. The boiled bark was used as soap. Today the berries, considered too seedy for jam, are sometimes made into jelly. Dried, powdered leaves were applied to wounds and burns to prevent scarring. A tea was made from the leaves for medicinal purposes. Hikers call it the soft fuzzy leaves “nature’s toilet paper.”” Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus | Native Plants PNW; see also the 104 entries for thimbleberry on BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

Description– “It is a dense shrub up to 2.5 meter tall with canes 3-15 millimeter diameter, often growing in large clumps which spread through the plant’s underground rhizome. Rubus is the genus of raspberries and blackberries, but unlike most other members of the genus, it has no thorns. The leaves are palmate, 5-20 centimeter across, with five lobes; they are soft and fuzzy in texture. The flowers are 2-6 centimeter diameter, with five white petals and numerous pale yellow stamens. It produces a tart edible composite fruit 10-15 millimeter diameter, which ripen to a bright red in mid to late summer. Like other raspberries it is not a true berry, but instead an aggregate fruit of numerous drupelets around a central core.” Calscape entry Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus

Similar species– The combination of the large size of the flowers, and the large size of the simple leaves, rules out everything else in the genera Rubus or Rosa.

Habitat– “It is found in moist to dry open woods, edges, open fields, and along shorelines. Wetland designation: FAC-, Facultative, it is equally likely to occur in wetlands or non-wetlands.” Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus | Native Plants PNW

Range– “Thimbleberry) is a species in the Rosaceae (Rose) family native to western and northern North America, from Alaska east to Ontario and Michigan and south to northern Mexico. It is widespread in California. It grows from sea level in the north, up to 2,500 meter altitude in the south of the range.” Calscape entry Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus

Reproductive timing– “Bloom time: May-June. Fruit ripens: July-September.” Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus | Native Plants PNW

Etymology of names– Rubus is the Latin word for blackberry/bramble. “The specific epithetparviflorus ([from the Latin for] “small-flowered”) is a misnomer, since the species’ flower is the largest of the genus.[7][3] The Concow tribe calls the plant wä-sā’ (Konkow language).” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubus_parviflorus. “…the drupelets may be carefully removed separately from the core when picked, leaving a hollow fruit which bears a resemblance to a thimble, perhaps giving the plant its name; it is also said that it may get its name from the Thimble Islands in Connecticut, though it is rarely seen there.” Calscape entry Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus

Eaten by– “The fruit is consumed by birds and bears, while black-tailed deer browse the young leaves and stems.[14] Larvae of the wasp species Diastrophus kincaidii (thimbleberry gallmaker)[15] develop in large, swollen galls on R. parviflorus stems.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubus_parviflorus

“The brambles rank at the very top of summer foods for wildlife, especially birds: grouse, pigeons, quail, grosbeaks, jays, robins, thrushes, towhees, waxwings, sparrows, to name just a few. The berries are also popular with raccoons, opossums, skunks, foxes, squirrels, chipmunks and other rodents. The leaves and stems are eaten extensively by deer and rabbits. Bear, beaver and marmots eat fruit, bark and twigs. Flowers are usually pollinated by insects.” Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus | Native Plants PNW; the moths Acleris britannia, Anacampsis fragariella, Proserpinus flavofasciata, Archips rosanus, Dysstroma citrata, Aseptis binotata, Zale lunata, Pseudothyatira cymatophoroides, and probably several others, use this plant as a larval host; the leaf beetles Scelolyperus schwarzii and Timarcha cerdo, as well as several stink bugs, probably feed on this species. Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubus_parviflorus

Thimbleberry, Rubus parviflorus | Native Plants PNW

BRIT – Native American Ethnobotany Database

Rubus parviflorus | Thimbleberry | Wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest

Rubus parviflorus – Burke Herbarium Image Collection

Another pleasant thing about Thimbleberries…the early medium sized leaves,when gently crushed, have a very sweet smell.

Cool! I did not know that. Thanks for the information Kate!

Yes, the berries are simply awful. Terrible. Completely inedible. Leave them on the plants. Just walk away. Keep going. Shooooooo!

(MINE! They’re all MINE!!!!)