To celebrate this being the 500th (499 by me, and one by my beloved nbo Morgan) profile of a group of living organisms (I can’t say species because some are just a genus, and others are a subspecies) on this site, I wanted to do something completely different. So I decided to profile something extremely commonplace in our region, the worm that most folks call a nightcrawler, because one of my goals has been to represent the diversity of living organisms in our region, and this adds the phylum Annelida, which is a new one for this project.

Speaking of that goal of diversity, I have profiled organisms from all 4 of the kingdoms (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, and Protista [by virtue of the slime molds], although Protista appears to be polyphyletic and will likely be split into at least two kingdoms, with the algae inhabiting their own kingdom) in the domain Eukarya (defined as having a membrane bound nucleus and organelles), which comprises all macroscopic life on earth. I would love to profile representative of the other two domains, but I’ll probably need better optics to identify any members of the domain Bacteria, and members of the domain Archaea, though they are present in every living organism, are very difficult to separate from their environment, and are well beyond my scope.

Within those four kingdoms I have profiled members of 13 phyla, (6 in Plantae, 4 in Animalia, 2 in Fungi, and a single one in Protista). So far it doesn’t seem like much diversity, but within those phyla I’ve got representatives of 28 classes (15 in Animalia, 9 in Plantae, 3 in Fungi, and 1 in Protista), and within those 27 classes are represented 92 orders (27 flowering plants, 25 invertebrates, 16 vertebrates, 14 spore producing plants, 8 fungi, and 2 Myxogastria), which means I’ve added 32 orders in my last 200 profiles. And finally, representing those 92 orders are 234 families (I’m tired of counting so I’m not sure how it breaks down), an increase of 84 families in the last 200 profiles. It should be noted, however, that the advent of relatively straightforward DNA testing is really shaking up the whole idea of morphology based taxonomy, and all of these categories will not look the same in 20 years, and some don’t look the same as when I profiled the organism. This whole list is just indicative of the fact that I set out to be wide ranging in my portrayals of living organisms, and have, to some extent, succeeded.

And now, back to our star attraction, Lumbricus terrestris, which goes by the common names common earthworm, dew worm, lob worm, variations of the term rain worm, vitalis, and the aforementioned nightcrawler. This is the species most people think of as an earthworm because they are common and large, but there are thousands of species of earthworms (earthworms belong to the phylum Annelida, the class Clitellata, the subclass Oligochaeta, and the order Opisthopora; nightcrawlers are in the family Lumbricidae), with over 30 species in our region, and Lumbricus terrestris is not even the most common of them.

For the most part positive identification to species of living earthworms is difficult to impossible, since it relies on characteristics that require good magnification, and they won’t hold still for that. However, patience and a good hand lens might be sufficient, (though I haven’t tried this yet), once one has become quite familiarized with the salient characteristics. For those with excellent color vision there is a photographic earthworm identification guide that might be useful, although it is for the UK. But we have many of the same genera, and even species, since the majority of our earthworm fauna is non-native and originated in Europe, and it is probably effective at getting one to a genus, if positive identification to species isn’t necessary. But it does have many limitations, as noted here. It should also be noted that immature worms (those lacking a clitellum, also known as a collar or saddle, which is the characteristic that places them in the class Clitellata) cannot be positively identified, and a surprisingly (to me at least) large percentage of the worms one sees are immature.

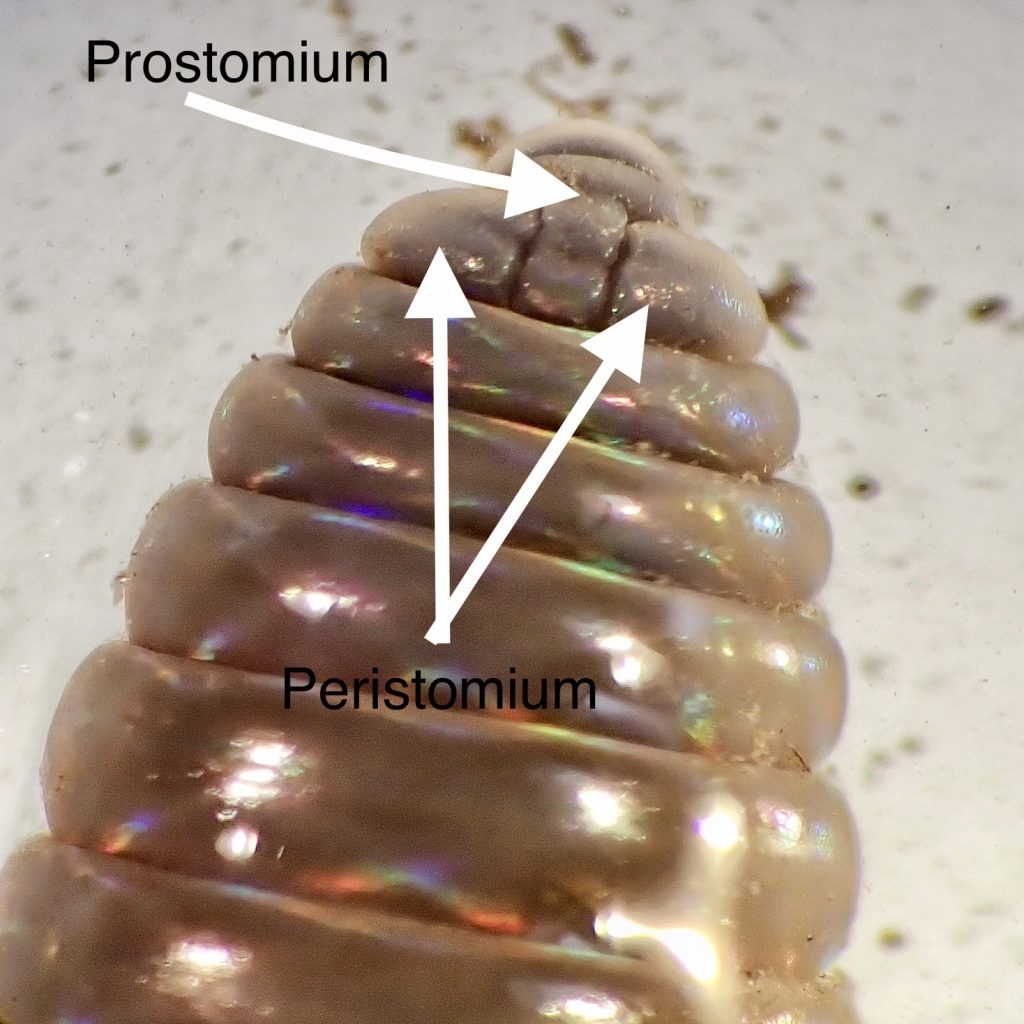

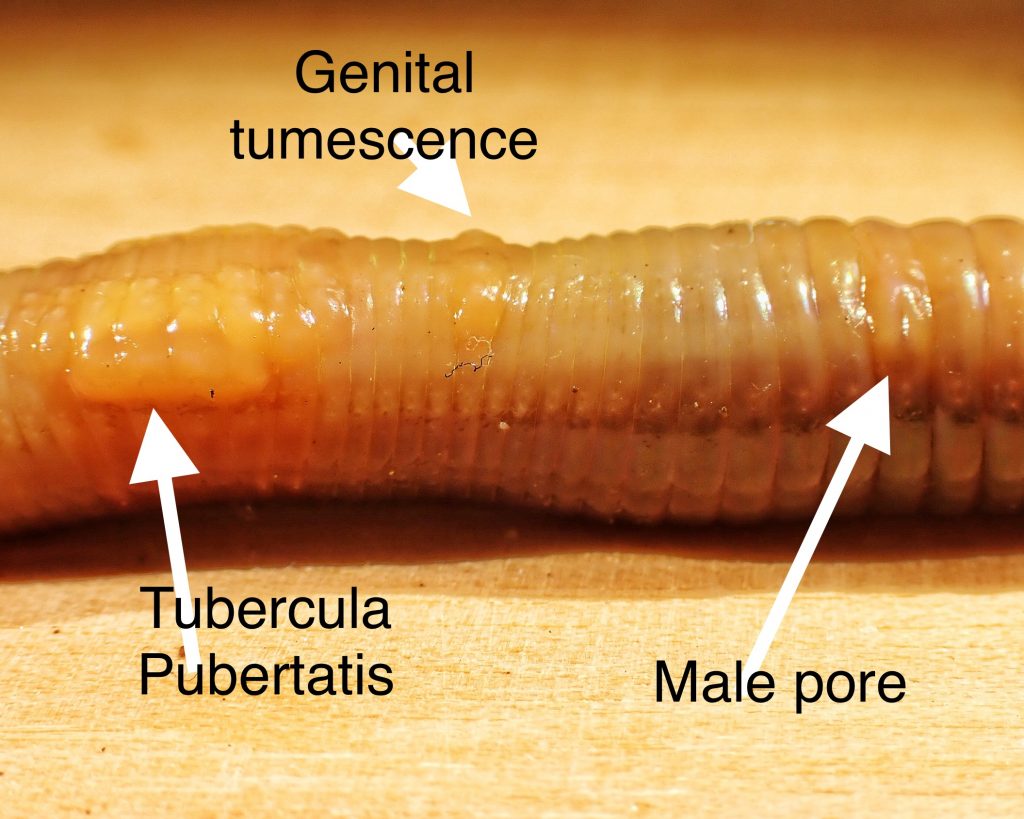

For these profiles, however, I prefer to get to species with a certain level of confidence, so I euthanized two of the worms shown here and examined them under the stereoscope. And, using Donald Schwert’s key in “Soil Biology Guide” (Dindal; 1990) , once I’d figured out what and where the prostomium, peristomium, male pores, and tubercula pubertatis were, taken the doubler off my ‘scope so I could see the whole area where I was counting segments, and determined how to tell the difference between a fold in a contracted segment and the actual next segment (you count the setae instead), it was actually a fairly straightforward process to identify this as Lumbricus terrestris, without my having to worry about what shade of red any of the parts were.

As most of you probably already know, earthworms are hermaphroditic, meaning each one has both male and female genitalia. But Lumbricus terrestris are incapable of self fertilization, and require a partner in procreation. They seek the most similar sized mate available, partly because breeding takes place on the surface of the ground while each is still anchored by the tail in their burrow, and a smaller partner may be pulled from its burrow during the ‘tug of war’ that ends copulation, which is a big risk, because the anchor allows them to retract very quickly into their burrow (anyone who has ever shined a flashlight on one of these in the dark can attest to how quickly they can pull most of their body into a burrow!), while unanchored individuals are quite vulnerable to attack. But this needs to be balanced by the fact that larger nightcrawler are, on average, more fecund (Michiels/Hohner/Vorndran; 2001). They assess size by visiting their neighbors, and sticking their head in its burrow. An interested party will then follow the visitor as it slowly retracts into its burrow. Besides the knowledge gained as to the size of the prospective partner, this appears to be a form of courtship, and reciprocal visits seem to precede most copulations (Nuutinen/Butt; 1997).

When mating occurs (and clear, calm nights seem to be the preference, at least as observed by Michiels/Hohner/Vorndran; 2001) they line up ventral side to ventral side, but facing in the opposite direction, with their clitellum against their partner’s spermathecae. Sperm then runs down a seminal groove to the clitellum where, with the aid of the tubercula pubertatis, it is forced into the partners spermathecae. Sometime after copulation is over (presumably to avoid accidentally capturing its own sperm) the clitellum of each worm again comes into play, producing a mucus ring (cocoon or egg capsule) which rolls toward the head as they back out of it, and into which from 4-10 eggs are placed, and then a few segments later, an appropriate amount of sperm from the spermathecae is added to the mix. Soon after sperm are added, the cocoon rolls off the worm’s head, seals into an oblong container, and the embryos are left to incubate.

Earthworms fall into three types: epigeic worms do not burrow, and live in the soil/litter interface; endogeic worms feed on soil and construct horizontal burrows in the top 1’ of topsoil; and anecic worms, like Lumbricus terrestris, who construct vertical burrows from which they reach the surface to breed, and to gather leaves of all types, including grass, which they then pull into their burrow to consume. These burrows are permanent, and, if my recent evenings of worm hunting are not anomalous, you seldom find mature nightcrawlers moving about on the surface without being anchored in their burrow. But I did find quite a few that lacked a clitellum and were moving about above ground. All of the mature worms in these photos were plucked from their burrows to be photographed.

Earthworms breathe and absorb moisture through their skin. They are eyeless, but have photoreceptors in their skin, and Lumbricus terrestris is highly photophobic, because they would dry out quickly in the sunlight. Some species of epigeic and endogeic worms are less sensitive to light, and are commonly found crawling on the surface during and after rainstorms, but nightcrawlers are strictly nocturnal, and if you find one crawling on the surface during daylight hours, something has gone very wrong for that worm. In fact it should be noted that I found many articles while researching this profile that purported to be talking about Lumbricus terrestris, but said things that clearly don’t apply to this species (although at least they did often debunk the myth that you can cut a worm in two and end up with 2 viable worms. This is patently not true. The tail end may survive for awhile without a head, but it cannot regenerate the head end and will assuredly die. They may however regenerate a tail, as long as the intact part extends beyond the region of the clitellum, but only if disease from the open wound or trauma don’t kill them first).

Earthworms of all sorts are quite beneficial to the gardener and composter, but non-native and invasive species like nightcrawlers can be quite problematic. There are many places in North American that do not have any native earthworms, because they were wiped out by extensive glaciation during the last ice age, which lasted from 100,000 years ago until 20,000 years ago. All of Canada, as well as the northeastern and upper midwestern US, were covered by glaciers during much of that period, and introduction (mostly due to inclusion with the soil of potted plants and by irresponsible dumping of fishing bait) of leaf and organic material eating worms like Lumbricus terrestris is having a devastating effect on their ecology, because the plants in these ecosystems evolved to germinate and root in deep humus soils, and the earthworms are eating up their seedbeds. Even in areas that have native earthworms, like most of the PNW, their introduction into nutrient rich areas is problematic, because they still alter the composition of the forest floor, and they may outcompete the native earthworms, as well as other native forest floor decomposers like millipedes.

At this point in time it is probably hopeless to try to get rid of these worms, and the best plan is simply to prevent further spread. In this they are much like Himalayan blackberries, and like the blackberries they provide a food source for many animals in areas where the human population has already irrevocably altered the native ecosystems. And lumbricid worms are survivors, having been around for at least 150 million years. So, rather than despising or venerating them, let us simply respect them as a wild living organisms, which exist because they can, and are supremely well adapted to being exactly what they are.

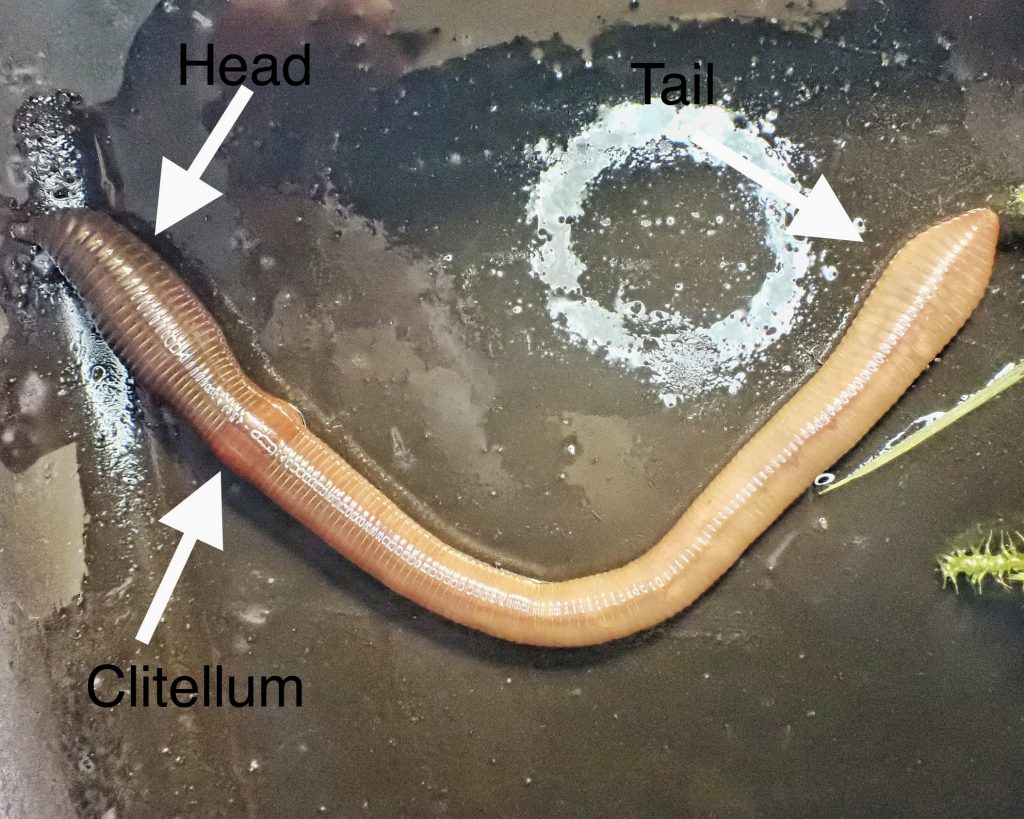

Description-Large (up to 8” long and 3/8” thick) earthworm with a dark, reddish brown to purple head section and a tan to violet tail section that is flattened at the tip; peristomium is completely divided by the prosomium; clitellum on segments 32-37; segments are uniformly colored (except for lighter colored genital tumescence).

Similar species-Everything I say here will be oversimplified, because a good key and magnification are required for a positive identification, and I can’t find any good online keys to share with you folk- the OPAL Earthworm Identification Guide is the best I can offer, and, as noted above, it has many limitations; other superficially very similar in coloration and body form Lumbricus spp. have clitellum starting before segment 30; superficially similar in coloration Aporrectodea sp. tend to be thinner, with a less flattened tail, and the peristomium is not completely divided by the prosomium; Allolobophoridella eiseni lacks tubercula pubertatis; other worms lack the dark, reddish purple head, or have bi-colored segments.

Habitat-Areas with moist (or at least seasonally damp) soil, and decaying leaves of forbs, trees, or grasses.

Range-Now cosmopolitan, but native to western Europe; commonly found west of the Cascades, though uncommon outside urban or agricultural areas along the coast, and found around urban areas and deciduous woodlands east of the Cascades, while absent in shrub steppe and juniper woodlands.

Eats-Decaying leaves of forbs, trees, and grasses, as well as humus rich soil.

Eaten by-Larvae of various flies, including Coenosia tigrina and horse flies; many beetles, including the Devil’s Coach Horse, Carabus nemoralis, Scaphinotus spp., Audouin’s Night-stalking Tiger Beetles; the carnivorous snail Haplotrema vancouverense; centipedes, many amphibians, including Western toads, Rough-skinned Newts, Northwestern Salamanders, and Ensatina, as well as foxes, moles, shrews, and a wide variety of birds.

Adults active– Nocturnal; year around, but often deep underground during hot, dry weather, and sub-freezing temperatures.

Life cycle-Breeding may take place year around during cool, damp periods; egg cocoons are deposited in the soil, and hatch in a few to several weeks, depending on the temperature; may breed every ten days; young nightcrawlers are identical to adults, except for size and a lack of clitellum; sexually mature in their second year; may live up to ten years in perfect conditions

Etymology of names– Lumbricus is the Latin word for an earthworm. The specific epithet terrestris is the Latin word for ‘of the earth’, an eminently applicable name for this species, especially since it is Linnaeus’ type species for the genus.

Biology of the Night Crawler (Lumbricus terrestris).

http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1555

Learn About Lumbricus Terrestris | Chegg.com

Lumbricus terrestris – Soil Ecology Wiki

Limitations of the OPAL Earthworm Guide for Species Identification | Earthworm Society of Britain

I love this statement:

In this they are much like Himalayan blackberries, and like the blackberries they provide a food source for many animals in areas where the human population has already irrevocably altered the native ecosystems. And lumbricid worms are survivors, having been around for at least 150 million years. So, rather than despising or venerating them, let us simply respect them as a wild living organisms, which exist because they can, and are supremely well adapted to being exactly what they are.

Thank you, Sharon! I’m glad you liked it!

I recall becoming intimately familiar with one particular Lumbricus terrestris over a couple of biology labs as Freshman in college and then being asked on a test, to recite the internal and external organs of the animal. And I recall gathering live worms and threading them onto a fishhook, good bait for bluegills in an Ohio farm pond

Thanks for the species accounts you send.

Thanks for your appreciation! I used to use these for bass and trout, but I guess our bluegills are too small because I had to use smaller worms for them. I still fondly remember worm picking the night before a fishing trip!

I really appreciate your postings-and all the effort to make them interesting and factual. Wonderful writing. I just discovered you and look forward to reading what came before.

Thank you so much for your appreciation, Julie!

500!!

Woot! Woot!

Thanks, Kat!